I was a scribe for the Chicago Illuminated Scripture Project

What would possess me to copy a chapter of the Bible by hand?

Long before books could be printed on a mechanical press or a digital printer and delivered to your door at the click of a button, they were written and copied by hand, word by word, with hand-cut pens in homemade ink on the fussy surfaces of animal skins. The books of the Bible were handed down as scrolls and codices, hand-copied by Hebrew scribes and early Christians. Copyists and illuminators turned scripture into works of art, gilded, colored, and illustrated, often with covers set in gold and gems.

The creation of many hands and thousands of hours of painstaking labor, a codex of the Bible was something the average Christian would never see or touch, much less read. Only churches, monasteries, and wealthy aristocrats could afford them. Today the Bible is available to anyone with an internet connection, searchable and in the translation and font size of your choice. We can buy illuminated scripture verses to hang on a wall, wear on a shirt, tattoo on our skin, or eat in birthday cake frosting. Why would we take the time and energy to write out the scriptures, when they are already accessible in so many places?

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Copying holy texts may no longer be a necessity, but it is a spiritual discipline that invites the scribe to deeper engagement with the word of God. It’s an old way of praying, like lectio divina, that has found new life during the pandemic.

In the early days of quarantine, the Roman Catholic Abbey of St. Gall in northeastern Switzerland invited more than 1,000 parishioners to create a completely handwritten and illustrated Corona-Bibel while they sheltered in place. The project inspired clergy in Chicago and Lincoln, Nebraska, to launch similar projects. While the American iterations are smaller in scope than the Swiss Corona-Bibel, focusing on select books of the Bible rather than all 66, the projects all share a common purpose: to gather people into community during a crisis and encourage them to experience the healing, comforting power of God’s word.

Chicago pastor Erin Coleman Branchaud says she was originally drawn to the practice of copying scripture for the sake of her own spiritual life, which was atrophying under the stress and isolation of trying to do ministry in a pandemic. She kept returning to a verse that appears in both Deuteronomy and Romans: “The Word of God is very near to you.”

“As close to us as a pen to paper, during a time when a lot of stuff felt so distant,” she says.

Branchaud and three other pastors from the Metropolitan Chicago Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America are leading the Chicago Illuminated Scripture Project. They encouraged contributors to write in any language, using any translation they chose, and to be creative with formatting, drawings, doodles, marginalia, personal comments, and critiques. The copied chapters will be consolidated into a single text and made available to the public as a hard copy or PDF, hopefully in time for Christmas.

I joined the Chicago project and signed up to copy Matthew 9. To start, I realized with a sense of irony, I would have to fish some blank paper out of my printer tray. I have a square standing desk on four slender legs, so I could romantically imagine myself as a medieval clerk, bent over my work. But clerks worked at desks set at a 45-degree angle, better for drawing ink from the tip of a quill pen; mine was flat, with a coaster for my coffee mug. Following the directions on the project’s website, I traced margins in pencil with a ruler, which, unlike a medieval clerk, I needed to rummage through four messy drawers to find. My pen was a fine-tip Sharpie, which did not drip, run out of ink, or need to be sharpened with a penknife. I opened a Bible webpage, chose the Common English Bible translation, and started copying.

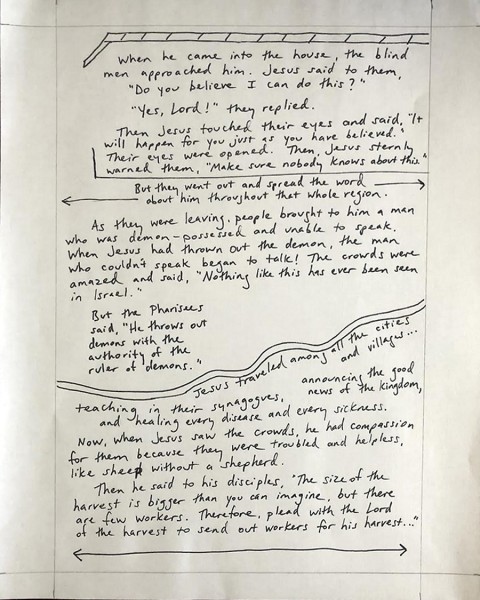

I wrote out the 38 verses of Matthew 9 twice—once to get a sense of the text and a second time to illuminate it. I have never taken a drawing class, but I do enjoy doodling. I decided I was going to create not something elaborate but something childlike and fun.

Because Jesus and the disciples were constantly traveling or “going out,” I drew some winding roads, arrows, and the waves of the Sea of Galilee. I drew a roofline to show when Jesus had gone into a house, and I enclosed one verse in an inner “room.” Matthew 9 includes two confrontations when opponents try to debate Jesus, so I wrote their challenges on the left of the page and his retorts and answers on the right. There is also a “sandwich” narrative: Jesus promises to go and revive a man’s daughter, encounters and heals a woman with a hemorrhage on the way, then arrives at the man’s home and heals the child. I tried to show that narrative hopscotch on the page. I added exclamation points because I like them, and I translated one line, “I desire mercy, not sacrifice,” into both Hebrew and Greek in the bottom margin, because I liked writing those alphabets in seminary and why not? (I practiced the Hebrew several times, but it still looks pretty clumsy.)

I won’t claim to be any kind of postmodern illuminator-monk, but I had fun. When I finished, it felt like I had been to church, which I hadn’t for a long time. With pandemic restrictions still in place, I couldn’t worship as part of a congregation or receive the Eucharist, but copying the text of Matthew made God’s Word sacramental in a new way. I had to pay attention to the text of the chapter as a whole, and it felt like I was reading with a part of my brain I have never used for Bible study before. The result was a deep and tangible immersion in scripture; I was inside each passage, not just looking on from a distance.

Copying felt liberating because it was new, but also because it was both serious and joyful at the same time—like play. As familiar or obscure as the words of scripture have become, writing them out in my own hand, I recognized they are still very much, as the writer of Hebrews says, “living and active.”

I am an Episcopal priest, but all kinds of people signed up for the Chicago project. Families worked together—one mother and daughter copied chapters 1 and 2 of Esther. Scribes included young children and teenagers, seminarians, and church leaders of different races, ethnicities, denominations, and faiths. Such variety reflects the original biblical authors and sources, co-organizer Fanya Burford-Berry points out. Alone at my desk, I joined that vast spiritual family, the communion of saints, with Hebrew scribes, medieval monks, and kids and adults in Chicago and around the world, picking up our pens together.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “How I became a scribe.”