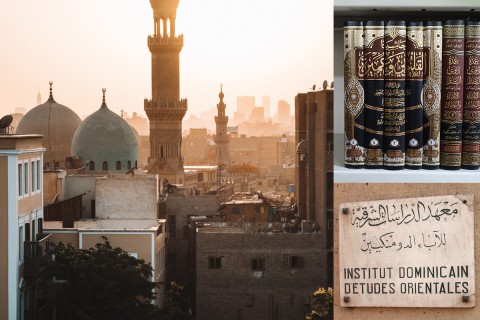

The Dominican friars whose library is transforming Islamic studies

How a rare books collection in Cairo expanded into a center for scholarship and interfaith conversation

Almost a hundred years ago, Antonin Jaussen, a Dominican friar, was sent to Cairo to set up a small priory. The plan was for him to establish a center of study in Egyptian archaeology. But Jaussen persuaded his superiors that the brothers who came to Egypt should instead focus primarily on Islamic studies. In 1953 the Dominican Institute for Oriental Studies (known by its French acronym, IDÉO) was formally established. It remains a community of Dominican friars.

Today that little corner of Cairo, a garden in the midst of a bustling city, has become one of the world’s foremost sites for Islamic studies—and an important catalyst for Muslim-Christian dialogue. Its aim is to track down, acquire, and catalog every available source, published or in manuscript, related to Islamic theology and philosophy in its first thousand years.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In January 2020, my wife and I set out on foot through central Cairo to visit IDÉO. With us were two friends: Naji Umran, a Canadian of Syrian origin who is ordained in the Christian Reformed Church in North America; and Hany al-Halawany, a Muslim lawyer and Naji’s Egyptian partner in promoting interfaith scripture study, a project supported by Resonate Global Mission in the United States. We had arranged to meet two of the brothers, John Gabriel, from Upper Egypt, and Jean Druel, from France, then director of the institute.

The IDÉO library includes manuscripts and published volumes in Arabic, English, French, German, Italian, and other languages. There are somewhere between 87,000 and 150,000 of them. In truth, Brother Jean told me, no one knows the exact number. “It depends if one counts the titles or the volumes, and then whether we count only different titles. For example, we have three different editions and one translation of the History of Damascus by Ibn Asakir, in 80 volumes. It is one title, four books—and 320 volumes!”

In many libraries, cataloging is a relatively simple task: look up the Library of Congress record, or consult Dewey decimal system rules, and put a number on the spine. For this collection, however, it is a daunting challenge. “Most works in Islamic theology are commentaries on earlier works,” said Brother Jean, “so we need to catalog them under at least two titles.” IDÉO also had to build a bridge between two incompatible modes of collection organization, he added. “Rare books collections and manuscript libraries are basically collections of objects,” he said, “so that is how they catalog. But research libraries organize by author and title. The two approaches can’t play together.”

And the picture gets even more complex in classical Islam. Many scholars write under several different names, he explained, depending on the context. These are often chosen to honor a distinguished forebear—and for that reason, six writers in six different periods may use the same pseudonym. To identify an author, therefore, one must cite not just a name but also a date and location. Making matters even more complicated, there are several ways of rendering written Arabic into roman characters. Five books in Latin that appear to be distinct treatises, with different authors and different titles, may actually be translations of the same Arabic work.

“So we had to create an entirely new cataloging software system,” Brother Jean explained. This was an almost unimaginably difficult task that has required many years of work, and it is still not completed.

IDÉO has offered to share its system, free of charge, with leading Islamic and Coptic libraries in Egypt, but there have been few takers. Most major libraries, said Brother Jean, have invested too much time and money in their own idiosyncratic systems. He suspects they might not want to admit that they don’t work very well.

During the week of our visit, several of the brothers spent long days at the Cairo International Book Fair, a two-week exhibition filling four huge exhibition halls outside Cairo. Books from 900 publishers, mostly in Arabic, were on display. On temporary shelves at the institute were more than a thousand books the brothers had already purchased for the library. We scheduled our meeting with them in late afternoon, after they had spent the entire day combing the new offerings in booth after booth of the fair.

Each year about 5,000 volumes are added to the collection and cataloged. In addition to purchases at the book fair, the brothers order new publications from European and American publishers. They also add published volumes and manuscripts, purchased or received as donations, some of them already centuries old. The focus of the collection is on classical Islam, the period from the seventh to the 17th century. More recent publications are acquired, too, if they bear on Islamic history and scholarship in that period.

Many users of the library have been scholars from the nearby Al-Azhar University and Mosque, a center of Islamic study renowned in Egypt and around the globe. Proximity has opened opportunities for collaboration. One-third of the users of the IDÉO library are students and faculty at Al-Azhar, and IDÉO residents offer seminars in Islamic studies for French-speaking students at the university.

In addition to these offerings for the university’s language and translation program, which admits only men, the brothers recently added seminars for female students enrolled in the human sciences program. It is striking that a university as renowned as Al-Azhar would work with French Catholics to educate their students about Islam, but such is the respect that the brothers have earned.

In 2016, Brother Jean told me, IDÉO received a €500,000 four-year grant from the European Union, making it possible to expand its programs and provide additional opportunities for Al-Azhar students. Among the activities funded by this grant are French classes for Egyptian students, study trips to France, and conferences that bring together Egyptian and European students and scholars. Last February, for example, the institute offered an online lecture by Asma Lamrabet, a Moroccan scholar, titled “The Question of Women, Central to Islamic Renewal,” arguing that proper interpretation of the Qur’an upholds the rights and dignity of women.

While the community has established strong relationships with Muslim scholars, a greater challenge, ironically, has been outreach to Egypt’s largest Christian community, the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria. Estimates of the Christian presence in Egypt vary, from 5 to 10 percent or more. All sources agree that 95 percent of Egyptian Christians are Coptic, following a tradition that has been dominant in Egypt since its break with Rome in the fifth century. The remaining Christians are mostly Protestant, with a small number of Catholics.

IDÉO contacts with the Coptic community, I was told, are very limited. “We visit the Coptic pope every year,” Brother Jean related. “He attended our 60th anniversary celebration in 2013, and he always speaks highly of our work. But we do not have an active working relationship with Coptic leaders or scholars. Recently we offered to train some Coptic monks in manuscript cataloging, and we hope they will accept our offer.” Tense relations with the Muslim majority in Egypt may have made ecumenical cooperation among Christians more difficult, and Coptic Christians have long been protective of their traditions and practices, which predate Protestant and Catholic missions by more than a millennium.

While contacts with local Christians are difficult, IDÉO is making important contributions to Christian-Muslim dialogue internationally. One of the nine brothers in residence is Paul Orerhime Akpomie, a Nigerian friar who joined the community five years ago. He was born and raised in Jos, in the central region of Nigeria, and was greatly affected by Christian-Muslim conflict there.

“In my childhood Jos was a very peaceful community,” Brother Paul told me. “I had a lot of friends who were Muslim. But in the early 2000s, when I had just completed my secondary studies, a political crisis arose that was linked to religion. And I actually witnessed friends being killed by other friends—Muslims and Christians who had grown up together, who were friends at school.”

At university in Nigeria, Brother Paul studied agronomy for five years. But then, he said, “trying to discern a path for my life, I decided to join the Dominicans.” That meant four years’ study of philosophy and four more of theology, which he completed at the Dominican Institute for Theology and Philosophy at Ibadan. It was there that a visiting American professor, also a Dominican friar, challenged his attitudes toward Islam.

“Because of the killings,” Brother Paul told me, “I had become angry and bitter toward Muslims. I thought Islam was only about killing and terrorism. In my class on interfaith relations, I was very aggressive in my questions for the American professor. As a Dominican priest, I asked him, why should he study a false religion?”

Rather than brush him off, his teacher took his questions seriously and encouraged him to take a more balanced perspective. The church’s understanding of other religions, the professor explained, is changing. The Second Vatican Council, convened by Pope John XXIII in 1962–1965, had called for greater respect and tolerance for other faiths, without compromising the central teachings of Christianity.

“Salvation is through Christ—that is what we believe,” said Brother Paul, describing how his thinking had changed. “But other people who may not have heard about him, or who were born into other faiths, may be saved if they truly seek to serve and obey God. And if they are saved, it is through Christ.”

After completing his studies, Brother Paul entered parish ministry in Nigeria, with no plans to continue studying Islam. “I wanted to learn more about parish ministry, and then perhaps study moral theology.” But the regent of his province urged him to sign up for a two-week live-in program with the brothers at IDÉO in Cairo, where he would join a group of Dominican brothers and one sister from different parts of the world.

“So I came to Cairo, five years ago. Wow! I was blown away, really. We had sessions with the brothers at the institute, we visited mosques, and an imam came to speak to us. We were encouraged to ask all our questions, even to express doubts about the whole approach.

“I was really touched by the openness of the brothers. This is difficult, they said: not everyone can embrace this path. It takes a lot of discipline. You must learn Arabic, of course; and you will face challenges from inside and outside the church. Egyptians who are not Christians are suspicious of your work and your motives. Coptic Christians, who may have had very bad experiences with Muslims, do not understand why we want to study Muslim teachings. And some of our Dominican brothers wonder why we waste our time with Islam when we could be studying Christianity.”

While some of the friars assist francophone parishes in Cairo, their primary work is engaging in, and assisting others with, scholarship on Islam. From its beginnings in the 13th century, Brother Paul reminded me, the Dominican Order has been devoted to teaching and preaching. Dominican friars identify them-selves with the initials OP for Ordo Praedicatorum, the Order of Preachers.

Brother Paul’s assigned work in the community is study, and in addition to an intensive course in spoken and written Arabic he is pursuing a PhD at the American University in Cairo. His topic is the interpretation and implementation of Shari’a law in contemporary Islam, especially the treatment of zana’ (adultery). Twenty years ago, he said, several states in Northern Nigeria adopted Shari’a law as the basis for civil and criminal court proceedings. When two women were convicted of adultery and sentenced to stoning, an international controversy erupted.

“The picture you usually get is that Shari’a is stagnant, outdated, and brutal,” said Brother Paul. “My argument is that it is not. It is based on God’s law, and that is constant, but it always adapts to a changing world. And that was what happened in these cases. The women had the right to appeal to a higher Islamic court, which listened to their arguments, found gaps in the evidence, and found them innocent.”

Mandated penalties under Shari’a law are often severe, Brother Paul went on, but in practice Islamic jurists interpret its directives in light of changes in society and respect for human rights, tempering justice with mercy. “That is what my thesis will argue. Looking at contemporary court decisions, and also at classical sources, I will argue that Shari’a law is intended to deter evil acts but not to break the person who does wrong. Its purpose is to strengthen the community.”

Raised in a part of West Africa where Christian-Muslim relations were once close and cooperative but have degenerated into deadly conflict, Brother Paul has joined a community devoted to research and scholarship as a mode of interfaith collaboration. Relations between the Muslims and Christians are no less fraught in Egypt today than in his home country, but IDÉO continues to promote cooperation.

I asked Brother Paul what he would want American Christians to know about the institute’s work. “My experience here teaches me: first, put your biases aside,” he replied. “Try to understand what is before you. To do that you must enter others’ worlds and see what they see. I may not believe as you believe, but I respect your experience, and my experiences are based in my own tradition. Then we can build trust and friendship, and we can learn to respect other traditions, not denying differences and challenges.”

For a research collection of such breadth and importance, the physical site of the IDÉO library is remarkably modest. “When people visit,” Brother John told me, “they expect to find a gleaming multistory research center, but what they see instead is a warren of underground rooms stuffed with metal shelves.” Its website is visited by thousands of users each day, researching titles and dates in several languages and studying the small but growing collection of digitized books and manuscripts.

The digital aspects of the collection have taken on greater importance, especially as the pandemic required a near halt to visitors. On a “toolbox” page of the website is a diverse collection of utilities for researchers: Arabic-roman transliteration utilities and comparison of different systems, instructions for setting up a Windows or Apple keyboard for entry of Arabic text, Arabic dictionaries, downloadable fonts for Arabic and Latin. Also accessible from this page are texts of the Qur’an in Arabic and in many other languages.

As we were finishing our tour of the institute and its library, brothers John and Jean recounted how their progress in digitizing and posting their collection—making everything universally available without charge—is bringing greatly increased traffic from search engines. The brothers have had to expand and update their servers.

Have you placed a button on your site, I asked Jean, so that visitors can make an online contribution to your work?

“Oh, no,” he responded cheerfully. “We don’t need to ask for donations. We work for Jesus.”

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “The friars of Cairo.”