The wisdom of not knowing

The information age feels like an all-you-can-eat buffet. I’m stuffed.

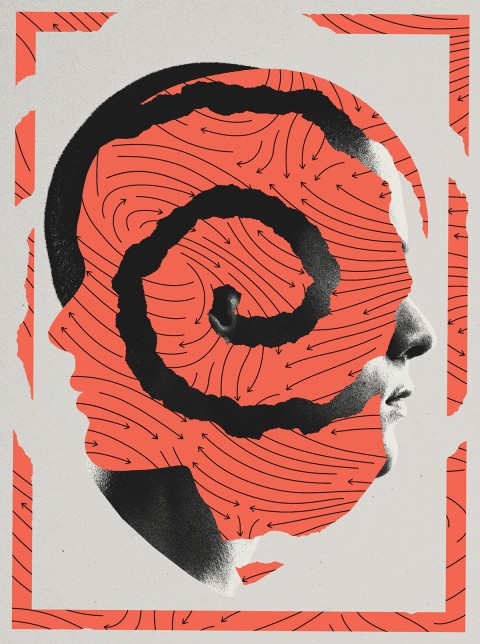

(Illustration by Chantal Jahchan)

I love church potlucks. There is grace in sitting down at a table with people known and unknown and making awkward, good-natured conversation, grace in the abundance of a single folding table that offers me lasagna, enchiladas, ham sliders, macaroni and cheese, fiesta chicken, pasta salad, black bean salad, couscous salad, fruit salad, eight kinds of bar cookies, apple pie, and a chocolate sheet cake. Who can resist trying a little bit of everything? I always put too much on my plate.

So I thought I’d love going to an all-inclusive resort: food and drink around every corner, all the time, for free. It was like a church potluck had exploded. The choices were beautiful and dizzying: seafood bars, pasta bars, potato bars, taco bars, salad bars, sandwich stations, omelet stations, carving stations, grill stations, cookie tables, ice cream, Jell-O, puddings, cakes, and as many watered-down cocktails as we could drink, all immaculately styled.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

At first it was a thrill. Then it got dull. Then it got weird. It all started to look like junk.

In much the same way, it used to be fun to look for the answer to any question I ever wondered about, at any moment, on the internet. But in the last couple years, answering all my own questions has gotten tedious. An infinite, all-inclusive buffet for the mind is now spread before us online. There is more information available to human beings than there has ever been in human history. We can find out just about anything we have ever wondered about, at any time, and at almost any place on earth.

The human brain is baited for novelty and the unexpected. We are primed to be addicted to knowing. Our mental appetite for new ideas and information evolved to be insatiable—in order to keep us on guard from danger, as well as to constantly alert us to new food sources and to learn more about our surroundings to survive. “Humans seem to exhibit an innate drive to forage for information in much the same way that other animals are driven to forage for food,” write Adam Gazzaley and Larry Rosen in The Distracted Mind. “This ‘hunger’ is now fed to an extreme degree by modern technological advances that deliver highly accessible information.”

The availability of novel information has grown to be constant and plenteous at a level we did not evolve to encounter. So much knowledge, but to what end? Our human desire for searching and learning can now overwhelm our attention span and immobilize us with distraction. For our ancestors, it used to take some effort to discover new information, perhaps even as much as finding food did. Even in war zones and other marginal places, many people in the world now have access to a mobile phone—meaning that finding information on the internet can be easier than finding food. Knowing has become a form of entertainment and compulsion, more like mindless snacking than a purposeful, sit-down meal.

Maybe I don’t always need to know what movie that actor was in, or what this person’s Facebook page looks like, or what that building is over there. The infinite buffet looks stale and plastic. Information I can serve myself on a whim has waxed dull. Going back for a tidbit answer to this or that question turns my stomach. I’m stuffed.

Jesus did not seem to like answering questions much during his time on earth. He did not give explanations so much as offer tricky juxtapositions, reject hierarchies, and interrogate religious rules and regulations. He would turn questions around, dodge them, answer with another question, or play tricks. After the crucifixion and resurrection, when he came back to meet his disciples, he did not explain what had happened or how. Instead, he said things like, “I am risen,” “Don’t be afraid,” “Peace,” and “Do you have anything to eat?”

Belief, for my Protestant ancestors, meant knowing the Bible, knowing what God asked of you, knowing what God wanted you to believe. My great-grandparents were Iowa farmers, and they read a chapter of the Bible aloud together every night after supper. Knowing the Bible and what it said—even the boring parts—was central to their relationship to God, to one another, and to their wider church community. For centuries, the West has valued knowing, comprehending, and solving. The Reformation put these values at the center of Christian practice, emphasizing preaching, scripture study, and catechisms—all in the vernacular—as more people learned to read and the printing press placed untold amounts of new information into their hands.

And yet, as technology is again changing our relationship to knowledge and learning, I wonder if the good news of the Christian life today is less about knowing than it is about opening ourselves to relationship and awe.

Many churches today describe their mission as “knowing God and making God known.” Is there anything wrong with this? Probably not. But how do we subconsciously understand what “knowing God” means?

I attended a talk by writer Annie Dillard at Orchestra Hall in Chicago in about 1990. Somehow, she was permitted to light a cigarette as she walked up and down the stage, talking to us. During the question-and-answer period someone asked something like, “You often mention God in your work. How can someone as educated and intelligent as you are be so certain God exists?”

She shrugged her shoulders, cigarette in hand, and said, “We’ve met.” Then she went on to the next question.

While the word know used to mean “to be acquainted with” or “to perceive,” in modern usage the emphasis has shifted toward having information about something or practical knowledge of it. The word now implies a sense of clarity and understanding that leaves less room for curiosity or mystery. What can we “know” about God, really? “Si comprehendus, non est Deus,” said Augustine: if you understand, it is not God. The word know is related to the Old High German word bichnāan, to recognize. “Recognizing” God sounds less poetic but makes a humbler confession than “knowing” in our modern sense.

Dillard’s books are meticulous chronicles of her observations—of a creek near her house, the nature of weasels, the writings of Teilhard de Chardin, the case of a neighbor’s child whose face is burned off in a plane accident. She writes in an informative narrative style, presenting both complex and sundry things in studied detail. Reading her books could be compared to going down an internet rabbit hole, perhaps.

But her aim is not to teach information or thrill with “you’ll never believe” trivia so much as to invite us to recognize the world as a place that can continually surprise us—with wonder and horror, with ordinary particulars and divine revelation, and sometimes with all four at the same time. When the Divine appears, God is elusive rather than friendly, mysterious rather than personable. Perhaps the only way to describe encountering this God is “We’ve met,” the shortest yet most perfect faithful testimony I’ve ever heard.

Of course, what makes faith faith is not that we can claim to know or have comprehended God. Faith does not entail a search for information or receiving clear answers to life’s persistent questions, although churches and Christians try with things like “Bible truths,” catechisms, creeds, and books upon books. I wonder if we often make what we think we know about God into an idol. When Job wonders why all those awful things happened to him, God does not offer an answer. God tells him that he is unable to know.

The anonymous author of The Cloud of Unknowing, a 14th-century guide to contemplative prayer written as a letter, says that to go deeper into the Christian life means bumping against “the cloud of unknowing” that must exist between us and God. The author, likely a Carthusian monk, wrote to his student: “Cut yourself off from needing to know things. Knowledge hinders, not helps you in contemplation. Be content feeling moved in a delightful, loving way by something mysterious and unknown.” The practice of contemplation is not necessary to follow in the way of Jesus, but it is a form of prayer many feel drawn to in our world of constant stimulation, new information, and the top ten ways to do all things.

Buddhist teachers describe a spiritual practice called “don’t-know mind.” Zen master Shunryū Suzuki writes, “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.” In other words, letting go of our opinions, assumptions, and accrued knowledge frees us to be more open to reality, new ideas, and compassion. This is not a mind numbing or a dodging of responsibility but an invitation to humility and freedom. It is the practice of meeting each moment and each person as a beginner or novice, as someone with an open and curious perspective. Saying “I don’t know” can make a space between my mind and the world, or my mind and the person sitting across from me—whether it’s a close family member, a dear friend, or a total stranger. Then maybe the Spirit can enter into that space and do a new thing.

“I don’t know” might be the truest creed we can confess in our modern age. We know (or think we know) so much. But we cannot really know who God is or why terrible things happen. We cannot know how to heal the world or save the church. We cannot predict the way anything will turn out, the right decision every time, or how to live our happiest life. To become a more loving, just, and wise people, we may need to let go of needing to know. Not to hide in ignorance but to quit spending our energy grasping after information or defending our rightness and righteousness.

To say “I don’t know” as a prayer, confession, or meditation is not to give up but to witness to the gap of unknowing between us and God. A gap not of cold emptiness but of wonder; a gap where there is more space for relating to one another and a clearing for the path that leads us back again to the mystery and glory of God.

Jesus does not ask his disciples to know or explain much. He asks them to do things, mostly very slow-moving things: to listen, to pray, to see, to love, to follow, and to serve the people around them. He leaves them (and us) with teachings and parables that do not give much in the way of clear answers but are more like spiritual puzzles or invitations to start thinking and talking together. Less like a beautiful, all-inclusive buffet, more like a do-it-yourself potluck.