The prophetic church in Ortega’s Nicaragua

One alarming aspect of the onetime revolutionary leader’s authoritarian turn has been the persecution of religious leaders.

“People are disappearing. In the capital, in smaller cities. At times in bars or nightclubs, under the influence of alcohol, someone might say the wrong thing,” said a young Nicaraguan woman who asked to be identified only as M for the safety of her family. “In the rural community where I live, people run the risk of being arrested, imprisoned, falsely accused of crime, and tortured psychologically. We’ve become scared to talk to our neighbors. You worry something you say might get repeated to the wrong person, and then you’ll end up in jail.”

Nicaragua rarely makes world news. In 1979, however, this small, impoverished country in Central America held the global spotlight as a group of revolutionaries overthrew the oppressive multigenerational dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza Debayle and instituted a socialist government. Named for Augusto Sandino, a revolutionary who resisted US imperialism in the 1920 and ’30s, the revolutionary Sandinista government instituted land reform, a massive literacy campaign, a vaccination campaign aimed at eradicating common childhood diseases, and efforts to improve sanitation.

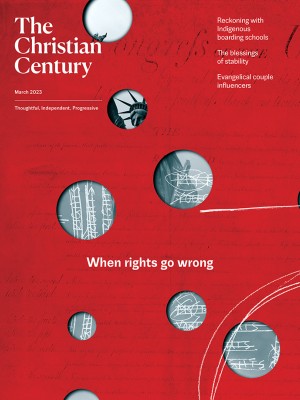

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

“With Somoza we had lived under a reign of terror and decided that the only possibility was armed struggle,” says acclaimed Nicaraguan poet and novelist Gioconda Belli, who participated in the revolution and later served in the Sandinista government. “I didn’t believe in using violent resistance at first, but eventually I was convinced. I came from an anti-Somoza family. I’d seen the struggle and above all the poverty, the terrible injustice, the huge differences between rich and poor under that government.”

The Sandinistas’ success was undercut by US-backed counterinsurgents known as Contras, plunging Nicaragua into civil war throughout the 1980s. Elections in 1990 ushered in a series of neoliberal, pro-US governments. In 2006, Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega was reelected and returned to power, where he has since remained.

Today, however, many Nicaraguans assert that the revolutionary who once overthrew a dictator has now become one himself. The current Nicaraguan reality serves as a warning for us all as to how easily a democratic government can slide into authoritarianism—and a reminder that amid injustice, Christians are called to solidarity with the most vulnerable.

“In the 1980s, Daniel Ortega was a mystical figure,” says Univision journalist and dual US-Nicaraguan citizen Tifani Roberts, who began her career covering the revolution for British outlets as a young student in the 1980s. “He was revered by many. Everyone who loved the revolution saw his commitment and identified with it. He was not pompous. You didn’t see him showing off money like other revolutionary leaders who lived in posh areas. He stayed in a low-class neighborhood in the middle of Managua. The people liked him because he was one of them.”

Roberts says that Ortega’s return to power was planned in 2006. Although opposition parties held power throughout the 1990s, Ortega urged Sandinistas in the Nicaraguan Congress to promote changes that would allow him to resume the presidency—for example, instituting a law in 1999 allowing a president to be elected with less than 50 percent of the vote.

Not all of the Sandinistas, however, desired to see Ortega return to power in the 21st century. “The world had changed, and the importance of democracy was clear,” says Belli. “Daniel Ortega had insisted that violence was necessary. We saw his view as outdated. We wanted a socially democratic left that was more respectful of private property and freedom of the press. And we wanted to work with the government rather than fighting against it.”

It was soon after Ortega’s return to power that I got a brief glimpse into the country he was leading. In 2007, I moved to Nicaragua to teach in a private Catholic high school. My outsider view of Nicaragua was one of an impoverished country ruled by a wealthy oligarchy. Opinions of the recently elected Ortega were mixed, but as I walked around Managua, I observed many projects devoted to repairing neighborhood infrastructure and promoting social welfare.

Though I worked in the school only for one year before heading back north, I visited again in 2012 as part of a delegation organized by the Alliance for Global Justice and School of the Americas Watch. During the trip I had the chance to pose for a photo with Ortega and shake his hand. My group met with him and many other government leaders, who were proud to show off the large degree of foreign investment they’d attracted in industry and agriculture. But these shiny developments concealed a dark underbelly I could not see. While Ortega was indeed making many efforts to raise the general standard of living, he was also slowly shutting down nongovernment media and undermining the country’s institutions.

“Ortega won a legal election in 2006, and that is the last clean election the country has had,” says Leslie Elin Anderson, a University of Florida political science professor who has been studying Nicaraguan politics since the 1980s. The 2006 election “was different because the right split against itself, dividing the majority vote. Ortega won with only a slender plurality. It’s not clear he would have won again, so he closed down elections, undermined the legislature and supreme court, and gradually established himself with no checks on his power.

“He was able to avoid a popular reaction because he was getting money from Venezuela and pumping it into social programs. Citizens ignored it until 2018; when the Venezuelan money dried up, he cut social programs and turned guns on the population. By then it was too late to stop him.”

Indeed, Nicaragua did make the international news in April 2018 when demonstrators across the country protested Ortega’s changes to the social security system. In a series of clashes that lasted several months, more than 300 people died—and demonstrations were subsequently outlawed, an act that drew UN condemnation. Since then, with non-state media shut down and institutions under control of Ortega and his wife, Rosario, Nicaraguan citizens find themselves living under an authoritarian regime.

“Ortega’s motive now is primarily for power and wealth,” says Anderson. “He is not in good health. He wants to elevate his son, in the pattern of the Somoza dictatorship. He did maintain a commitment to social programs after he was elected in 2006, while he was destroying the democracy and weakening the institutions. Now that the money has run out, he is only interested in power. But he was always a very heavy-handed leader, much like his friends Vladimir Putin and Nicolás Maduro. Putin and Ortega are very close buddies, just as Putin is very supportive of the dictatorship in Venezuela,” she says.

“I don’t think Ortega was more idealistic when he was young,” says Belli. “He was closed. Now, his wife has an enormous influence over him and a great organizational ability. It gives him more power—and now his wife is vice president. They are becoming a monarchy. All orders are coming from above and being fulfilled. There are no parties, no regard for law or the benefit of people. They are maintaining power with the police and military; without this, they’d be gone, because the will of the Nicaraguan people was for them to leave in 2018.”

One particularly alarming aspect of Ortega’s consolidation of power has been the persecution of religious leaders, primarily in the Catholic Church, to which a majority of Nicaraguans belong. “The Sandinistas and the church have a long history of reversals in their relationship,” says Anderson. “The members of the church in Central America who were informed by liberation theology, such as Ernesto Cardenal, were sympathetic to the Sandinista revolution. There were also church leaders in opposition, many put into place by the conservative Pope John Paul II.”

Anderson notes that in 2006 “Ortega succeeded in winning the clergy’s support. But since witnessing the killing of civilians in 2018, some clergy have come back into opposition. Some have been arrested. There are many political prisoners being starved to death.”

Because of the widespread fear of imprisonment and torture, it was extremely difficult to find any church leaders willing to be interviewed for this article. But one Nicaraguan priest, who has lived and ministered in the United States for several years, agreed to speak anonymously. “There are many priests who’ve been supporting the people strongly, helping them to leave,” he says. “I have a priest friend who lives in fear of being exiled or incarcerated. Starting in 2018, he opened the church as a hospital for the wounded. Those hurt were tended, including young Sandinistas hurt in the protests, because the government had said everyone who participated in protests could not receive medical attention in hospitals,” he explains.

The priest adds that, in his view, the Nicaraguan church is a strong prophetic voice. “The role of the prophet is to speak and denounce. There are two leaders I see doing this. One is Bishop Rolando Álvarez, of the Matagalpa Diocese. He has spoken clearly and directly about the injustices, the persecution, the silencing of people,” he said. “The other person with a strong voice is Monsignor Silvio Báez. He speaks clearly. . . . In 2018 we thought he was going to be like Óscar Romero, assassinated, but the Vatican intervened so he could be exiled.”

At the present moment, the Nicaraguan government states that Bishop Álvarez is under house arrest. However, Roberts, the Univision journalist, comments that many people do not believe this claim. “His parents have not seen him. Some fear he has been kidnapped. The regime will say whatever they want.”

Monsignor Báez, meanwhile, is preaching at St. Agatha Catholic Church in Miami, where Roberts is a parishioner. Although he avoids speaking to the media about the situation in Nicaragua, he addresses the injustice from the pulpit, with homilies recorded and shared on social media for people throughout the world to see. “He’s careful not to be too direct about it, but often we can tell his homilies are about Nicaragua,” Roberts says.

In his October 23 homily on Luke 18:10–14, the parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector who come to pray in the temple, Báez commented, “Faith is not a privilege that immediately brings us closer to God. Following commandments does not guarantee holiness. The Pharisee follows ‘the religion of the self.’ He talks to himself, not God. What Jesus criticizes aren’t his good works but the fact that he lives closed within himself.”

He went on: “Today there are many politicians who act like the Pharisee, manipulating religion for their benefit, invoking God, calling their successes blessings of God. Often they are authoritarian and unable to recognize their errors. They practice a religion based on ‘I,’ justifying their corruption and cruelty. A Christian politician lives authentically listening to God and others—especially those who offer critique,” he said in the homily, which was recorded and shared on St. Agatha’s Facebook page.

According to the anonymous priest in the United States, Báez is an advocate for people facing persecution. “He is a voice for the people. He reminds us of the most important thing: that all people should have the right to be in disagreement with a government, any government. They have the right to live in peace. They have a right to work, safety, school for their children. This is the most basic thing, the fundamental rights of everyone. These are also the teachings of Christ: love. Ortega’s government is not practicing this.”

For ordinary Nicaraguans, the current reality is discouraging. “I don’t know what’s going to happen in the future,” says M, the anonymous woman quoted at the beginning. “There’s no future for most young people because there is so little work available. Thousands of people are leaving for the US—you hear rumors of this or that person, this or that family leaving. But that journey is very dangerous. People get robbed by coyotes or kidnapped in Mexico,” she says. “I’d like to see the US put pressure on the government, but they have consolidated their power, and they have many countries who support them, such as Russia.”

Anderson, the political scientist, says that the Nicaraguan-Russian alliance should sound a particularly loud warning bell for the United States. “There is talk of Putin putting nuclear warheads on Nicaraguan soil,” she says. “That might make the US wake up. Because of the reforms of the ’90s, the Nicaraguan army is much smaller than other armies, like the Venezuelan one. It’s not a major force Putin could use. Some people think the Ortega dictatorship is unstable and will come down. But a lot of people may die first. I have friends—university professors, NGO workers, journalists—who are currently political prisoners.”

Asked what could have been done to avoid Ortega’s consolidation of power, Anderson replies that she sees caution signs for the United States in this situation. “Nicaraguan citizens are extremely poor and didn’t understand that once you lose democracy, it’s gone. They thought social programs and social security payments were more important than preserving democratic institutions, so they looked the other way as Ortega consolidated power,” she says.

“For democracy to break down, you need an autocrat with an agenda of destroying it,” she goes on. “Nicaraguans have that in Ortega, and we have that in Trump. The Nicaraguans couldn’t get rid of Ortega. We did remove Trump. But one thing Trump has that Ortega didn’t have is a large, supportive, mobilizing party. Ortega doesn’t have that. This is why he has moved to corrupt institutions and put in people who will rubber-stamp what he wants. Trump has an advantage Ortega doesn’t have. Also, the opposition to Ortega abdicated responsibility and allowed that to happen. In this country, the opposition is aware that there is a serious threat to democracy and are trying to act on that.”

Despite seeing their radio stations shut down and their leaders imprisoned or exiled, the church has continued to denounce dictatorship and support the Nicaraguan people. “In all of Central America, the poorest of the poor countries, the church has always been closest to the poor,” says Roberts. “When a campesino suffers illness or crime, they don’t go to the police—they go to the parish. Padre, my son needs a job. The poor trust the church more than the mayor, the police, the politicians. By historical tradition, for years and years, the church has been the one constant in the lives of the campesinos—protecting them, helping them, counseling them. They have authority when it comes to their sheep. You cannot change that,” she says, noting that during the 2018 protests, many young demonstrators took refuge in the cathedral and other churches.

The anonymous priest says he finds hope in urging people in the United States to combine prayer with action and advocacy. “I want people in the US to pressure Congress to use the power it has to pressure the Ortega government,” he says. “I’d like people to become aware that Nicaraguans are a people suffering. We hear in the news about Ukraine, Myanmar, and Venezuela, but Nicaragua is also suffering. Divided families, young people without much future to look forward to, no freedom of expression, no chance to live with their dignity as sons and daughters of God.”

He says that prayer remains a source of hope. “Since the start of the conflict in 2018, my heart was filled with hatred against Ortega. I remember when the Nicaraguan Bishops’ Conference began to pray the rosary for salvation. I joined them. There was no change in Nicaragua, but there was a change in my heart. I realized that hatred would only fill my heart with negativity. I was able to stand united with Nicaraguans in prayer, to pray for a transformation in the hearts of the oppressors.”

He adds that while he is saddened by the reality that has unfolded in Nicaragua, he remains hopeful and proud of his country. “My heart is very sad because I do not see much future for the young people of Nicaragua. At the same time, I am proud that they were the ones who helped Nicaraguan society wake up in 2018. They are heroes making history. Also, all those men and women religious helping the people have shown great courage. Azul y blanco,” he says, referencing the sky-blue and white colors of his nation’s flag. “I am proud to be Nicaraguan.”