OncoMouse and me

A genetically engineered animal helped me rethink the imago Dei. It might also save my life.

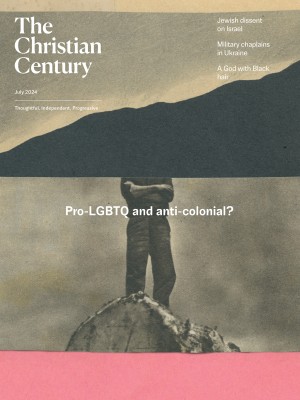

(Illustration by Martha Park)

When I walked across the threshold into what Susan Sontag called “the kingdom of the sick,” I held the belief that the imago Dei was a metaphor that set humans apart and demonstrated God’s love for us. Now a small relative of mine, a transgenic lab mouse known as OncoMouse, is demolishing that understanding of what it means to be human. OncoMouse shatters all the traditional boundaries I’ve held so dear: human/nonhuman, nature/culture, artificial/natural. OncoMouse reminds me that the image of God is reflected in, with, and under all of creation.

OncoMouse is kin to me, and the research for which she is being used could possibly one day save my life. Over the last seven years I’ve had three kinds of cancer: breast, melanoma, and solitary fibrous tumors. This last one is incredibly rare. Only about one person in a million per year gets it, and when it led to a sepsis that threatened my life, doctors told me my condition was even more rare. Internal medicine residents started writing it up for the medical literature.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

My cancer is rare. But even without the cancer, I am an utterly unique human being among all the 117 billion humans who have ever lived. And according to my religious tradition, the one thing I share with all other human beings is called the imago Dei.

OncoMouse, on the other hand, is the first patented mammal in the world. She is an actual animal, a type of mouse more than an individual, who has been genetically engineered to carry a specific gene called the oncogene. This gene makes OncoMouse especially susceptible to cancer, and thus she is used in cancer research. As a transgenic animal, she blurs the boundary between humans and nonhumans. She breaks our understanding of what it means to be human and, consequently, she challenges what it means to be created in the image of God.

I now feel and experience a strong sense of kinship with OncoMouse and all of her mouse colleagues, and I am reluctant to separate them from the imago Dei. While we treat OncoMouse as a commodity—we buy, sell, experiment on, and even kill her—this does nothing to undermine my kinship with her. Like my own, this mouse’s traits emerge through complex interactions with unpredictable timelines and draw her into new chimeric realities we hadn’t yet thought about.

Cancer challenges not only the distinction I make between mouse and human but also the boundaries of my inner and outer worlds. Terry Tempest Williams famously said that an individual doesn’t get cancer, a family does. This has proven true in my case. Cancer has affected and perhaps infected every one of my relationships. My grandparents had cancer, and I inherited the genetic propensity for cancer from them. Cancer runs through family memories and family bodies.

The science of epigenetics reflects how the behaviors of all creatures and their environment affect the expression of genes that are inherited within family systems. My family history includes not only my immediate human family but also the environment in which I grew up and lived. Epigenetics does not change my DNA, but it can reflect the way my body self-interprets and expresses that DNA. If my environment and my ancestors’ behaviors are that powerful, then surely those interrelationships shape the imago Dei.

I’ve also stopped thinking about cancer as something that has happened only to my body and not to my whole self. Within me, cancer is an entanglement of knots and intersections. My body goes into uncontrolled growth that it is tempting to call “foreign,” even though it’s mine and is the result of evolutionary processes. While we often call cancer treatment a “battle” as if against an invading force, it isn’t really that. This cancer comes from the same processes that create life as well as destroy it.

And now I work with this cancer inside me, joined by the latest scientific research that meets my organic matter in techno-protocols. Like me, medical practitioners often have no idea what will happen when they intersect treatments with the highly uncertain territory of my body. Maybe they have some statistics they can use, but in the case of my cancer, statistics are pretty much meaningless.

There is no doubt that cancer is intersecting with me—all of me, mind, body, and spirit. I am a body self, not just some parts that need to be fixed and some parts that don’t. “Lord,” Augustine writes in his Confessions, “you turned my attention back to myself. You took me up from behind my own back where I had placed myself because I did not wish to observe myself, and you set me before my face.” This is what God has used cancer to do for me. I have now looked at myself inside out, become aware of minute processes within myself, wondered at the relationship between inner and outer and backward and forward, and concluded that the imago Dei is so much more than I previously understood.

Cancer reveals not only our evolutionary ancestry but also our cultural and spiritual genealogy: we are completely dependent and interdependent on all of creation. We are relatives and neighbors with all of it. As all of these families of origin diverge, breed, merge, and remerge, we learn from and with each other. The scale of evolutionary time reveals how recent human beings are to the scene of God’s ongoing creation. We are just one minute before midnight, with a whole day lived without us. The nature of the imago Dei, mysterious as it is, is clearly relational, literally in the dirt of Adam from which God created us.

This is what it is to live in the image of God: to live in a present charged with uncertainty and in the presence of all that is and all that has ever been. Sometimes it feels like those moments during a summer derecho when I see the lightning bolts piercing the greenish storm clouds, and I think I should run to the basement. But I stand watching, mesmerized by a whirlwind of wonder and fear.

Cancer has taught me that to live in the imago Dei is not to wait for some kind of inner transformation or motivation. It isn’t that I am going to get the answer right or know what God’s plan is, finally. I live days and days waiting for scan results and then more days hoping I’ve read them incorrectly, that the cancer hasn’t spread, that for once the uncertainty of all of this will work to my benefit. But then I am struck again by God’s radical grace that draws me into the sacrament of each present moment.

None of us knows the future. But we can know the resurrection that is now, in this moment, and not in any other. And we live it together, with those around and within us.

There is so much I don’t know. But I do know that I don’t want to spend my life fighting a battle against myself. Instead, I’ll know that I’m kinfolk with all of life that reflects the image of God who creates and loves us.