Nicene myths

The Athanasians won, so they got to tell the story of Arianism. Arius would barely have recognized it.

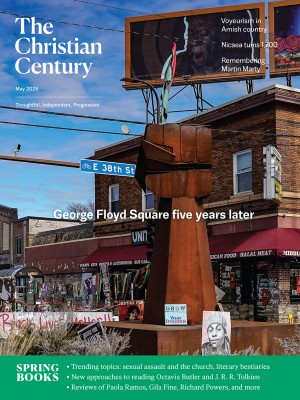

Emperor Constantine burning Arian books at the first Council of Nicaea in 325, ca. 1640s, by Carlo Magnone (Heritage Image Partnership / Art Resource, NY)

In May 325, 300 bishops responded to the summons of the Roman emperor Constantine, gathering at Nicaea, in present-day Turkey, to discuss pressing theological controversies then dividing the church. That event, the Council of Nicaea, has featured prominently in the church’s memory, from historical accounts of the church’s theology and its relationship with state power to artistic visions of the proclamation of orthodoxy. In this 1,700th anniversary year, what must strike us most powerfully about that council is the very different ways we tell our stories—and how one version overrides and eliminates its competitors. It comes to be the plain truth, even the only truth.

As usually recounted, the Nicene story tells how the early church formulated its doctrine of the Trinity, in which Father, Son, and Holy Spirit always coexisted. John’s Gospel starts by declaring that the Word, the Son, was there “in the beginning.” Around 310, the Alexandrian presbyter Arius taught the seditious rival doctrine that the Father, who genuinely was from eternity, had generated or begotten the Son. This might have occurred mere nanoseconds after the moment of creation, but even so, there was a time when the Son was not, and that fact marked a fundamental distinction between the two persons. The Son was begotten and was subordinate to the Father. The Alexandrian church condemned Arius, and that decision was decisively endorsed at Nicaea, where only two of the assembled prelates dissented. Athanasius emerged as Arius’s main foe and the nemesis of his cause. Christian orthodoxy was saved.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In recent decades, scholars such as Rowan Williams have devoted immense attention to Arius and Arianism, stressing that the two are by no means the same. Their scholarship raises questions about the Nicene conflict, questions that should be asked about many of the church’s debates.

The first is, How do we know? In early times, the winning side in theological struggles customarily commanded the utter destruction of most of the documents in which their rivals had dared present their views, and Nicaea was no exception. Not only were all Arian documents to be destroyed, but the death penalty awaited those bold souls who tried to conceal such contraband items. Obviously, then, we can never know what the Arians believed with any precision, and we are never able to report these controversies in any kind of fair or balanced way.

The other critical question, which is so key to the rhetoric of the debates, might be framed as, Who’s on first? It involves deciding which of two sides in any given conflict could legitimately claim to be presenting an old, established position, as opposed to an upstart novelty. This mattered so crucially because, before modern times, truth had to be rooted in immemorable antiquity, which in the Christian context meant the world of the Bible and of the earliest church. Each side believed that it was presenting authentic archaic truth, or what we might call original intent, while rival opinions must have been cooked up very recently, presumably following the whims and ambitions of one deviant thinker. To borrow a Chinese maxim, “Woe to him who willfully innovates.” This explains the age-old Christian tendency to present any competing opinion as an ism associated with some named individual, such as Arius. To adapt an old joke, we are both doing the Lord’s will: you in your way, I in his.

Of course the pro-Nicene party claimed that their own teachings were the authentic voice of the earliest church—how could they do otherwise? But we need not believe them in this. Despite later orthodox mythologizing, Arius was anything but a reckless innovator. Most of the arguments that attracted the disapproval of his superiors came from his determined attempts to assert Christian orthodoxies against the valentinian and Manichaean sects that remained so potent in the Egypt of his day. Contrary to what those sects preached, Arius declared that Christ must not be seen as some kind of mystical emanation of a divine force but rather had his own distinct identity. In most respects, Arius’s theological views accorded well with the standard views of the great thinkers of the previous two centuries, with Justin Martyr, Origen, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, and others—the ones we call the ante-Nicene fathers. To a greater or lesser degree, all had preached the Trinity, but they also taught that the Son was subordinate to the Father, and they implied begetting in time. Arius and Athanasius alike claimed Origen as their great inspiration, and both sides quoted that brilliant thinker with equal enthusiasm.

Often, such early understandings drew on biblical passages that tell how God created a Wisdom figure who served as the agent of creation. Proverbs 8 offers an influential and much-quoted account (“The Lord created me at the beginning of his work, the first of his acts of long ago”). In understanding Jesus’ messianic role, believers from earliest times had freely raided the Psalms, especially the royal Psalms 2 and 45, in which God speaks of choosing, begetting, or anointing a king. These passages could be read to suggest not only that God had appointed Jesus to Sonship but that this occurred at a specific historical moment, a given “day,” presumably the resurrection. Passages in both Romans 1 and Hebrews 1 can be used for these purposes. Any later thinker trying to support broadly Arian positions could at least claim to find solid biblical ground.

Early theologians had a special incentive to draw distinctions between the persons of the Trinity because of the grave challenge they faced from the opposite intellectual tendency, namely, that all those persons should be merged into an undifferentiated unity. Bitter debates in the third century had focused on the ideas attributed to Sabellius, who supposedly saw all those divine persons as modes of a single indivisible reality. The textbooks use such technical terms as modalism and Monarchianism. Reputedly, Sabellius had coined a potent word to describe his system, declaring that all those persons were of one substance, one ousia, and that they were therefore homoousios, consubstantial. Orthodox thinkers viewed such language with horror.

But it resurfaced, in a somewhat different context, in the debates between Arius and Athanasius. That once-abhorred word homoousios famously ended up in the creed formulated at Nicaea, which in modified form has been recited by so many billions of believers in later eras. That inclusion was chiefly the work of Constantine, who personally insisted on it, likely with little sense of the earlier connotations. With imperial toleration only a decade old, the fathers gathered at Nicaea were in no position to spurn the opinions of the man Eusebius of Caesarea called “our most wise and most pious emperor,” who was so anxious to prove his credentials as mentor of the emerging church.

The two sides in the Arian debates faced concerns that were close to identical. Each wanted to preserve God’s unity while recognizing the distinctions between the persons. At the same time, they did not want those distinctions to become so stark that believers might lapse into some kind of polytheism, which in the religious atmosphere of the time would have constituted an unforgivable concession to paganism. In the event, the Athanasian side triumphed—and retroactively reconstructed its enemies as advocates of an Arianism that presented a crudely unitarian view that denied the divinity of Christ. It was Athanasius himself who constructed the package of supposed beliefs that he portrayed as Arianism, which has been endlessly cited as authentic by later historians. Such an image would have been barely recognizable to Arius himself, who in that sense was never an Arian. A century later, something similar befell Nestorius, who was just as far removed from the “Nestorian” caricature.

Church history reimagined Arius as the model of a heresiarch, ambitious, arrogant, and ultimately willing to destroy the church’s belief to appease his own vanity. He was literally demonized in art and commonly juxtaposed with Judas Iscariot as the betrayer of Jesus Christ. In Dante’s Paradiso, Arius appears alongside Sabellius as one of the unskilled blunderers who sporadically roil the waters of true belief.

The Council of Nicaea concluded with what appeared to be an overwhelming assertion of unity, which was in fact thoroughly deceptive. Among those who voted for the new creed were some, and perhaps many, who thoroughly disagreed with it but who would not publicly resist imperial decisions. Those covert critics were content to bide their time and to fight the battle for truth once more when occasion arose. One such was Eusebius of Nicomedia, who served as mentor of Constantine’s son and long-serving successor Constantius II. Under Constantius, new church councils in the 350s progressively dismantled the obnoxious Nicene formula. Meanwhile, new sects took Arian views to lengths far beyond anything that Arius would have tolerated, even asserting the essential difference between Father and Son.

Just how passionately interested ordinary people were in such ongoing struggles is suggested by a famous description of Constantinople in these years. As a clerical visitor reported, with sniffy disdain, “even the humblest were all of them profound theologians, and preach in the shops and in the streets. If you desire a man to change a piece of silver, he informs you wherein the Son differs from the Father; if you ask the price of a loaf, you are told, by way of reply, that the Son is inferior to the Father; and if you inquire whether the bath is ready, the answer is, that the Son was made out of nothing.” Could anything be more appalling than ordinary laypeople caring about the doctrines of their church?

The empire settled on a theological regime that is sometimes termed Semi-Arian but which can also be seen as a return to older pre-Nicene traditions. In 360, the official creed declared at a new council at Constantinople claimed belief in “the only-begotten Son of God, begotten from God before all ages and before every beginning by whom all things were made, visible and invisible, and begotten as only-begotten, only from the Father only, God from God, like to the Father that begat him according to the Scriptures; whose origin no one knows except the Father alone who begat him.”

So much of this looks like our familiar language, but we note the key differences. The Son is “like to the Father”—rather than of “one being with the Father,” that is, of the same substance, the same ousia. In fact, that whole philosophical language is conspicuous by its absence. Throughout the 350s and 360s synods and councils agreed that such loaded terms as homoousios and homoiousios (of like essence) were confusing—and unbiblical—and as such should be avoided. As far as possible, they tried to settle the long controversy by agreeing not to talk about it.

Nicaea only came back into full vogue with the later emperor Theodosius, whose Council of Constantinople in 381 restored its principles. Technically, the creed that Christians have recited ever since is not Nicene but Nicene/Constantinopolitan—absolutely following the principles of Nicaea, though with some verbal adjustments.

After however long a historical interval, Nicaea won, and so did the assertion that the Son was homoousios with the Father. As later historians told the story, that outcome came to be portrayed as inevitable and, moreover, as far more rapid and popular than it was. That interpretation encouraged the myth of the Great Council, which in practice was probably the greatest legacy of the events of 325. In this idealistic vision, such a gathering of the church’s leaders would always be an effective and decisive way of resolving its divisions, no matter how severe they seem. In practice, such a vision has proved illusory, and the last ecumenical council acknowledged by all the world’s churches met way back in 787.

In long hindsight, that first Council of Nicaea became a moment of crucial significance for the church and the Christian faith. Some have even wondered how the faith might have developed otherwise. Hilaire Belloc speculated that the triumph of Arianism “would inevitably have led in the long run into mere unitarianism and the treating of our Lord at last as a prophet and, however exalted, no more than a prophet. . . . It would have rendered the new religion something like Mohammedanism.” Belloc might have been recalling St. John of Damascus, who in the eighth century had presented the improbable tradition that Muhammad owed many of his beliefs to a stubbornly unreconstructed Arian monk. In this view, Arius stood in a kind of anti-apostolic succession that culminated in the prophet of Islam.

Tracing alternate historical pathways is always a perilous endeavor, but in this case, Belloc was on even shakier ground than in most of his historical pronouncements. He was working from the common mythology that so thoroughly confused Arius’s opinions about the Trinity with what he might have thought about Christology, about which we know far less. For the sake of argument, let us assume that Arius’s position had won at Nicaea, and that the church had resoundingly proclaimed the Son’s subordinate position. Would that have made any significant difference to Christianity as it shaped life and devotion through the centuries? Surely, Christians would in practice have carried on exalting the figure of Jesus through art and music. Meanwhile, surging popular devotion to the Virgin Mary would presumably have led to the same kind of artistic explosion from the fifth century onward that we actually find in our Nicene reality.

In terms of the visual arts, we can learn much from the great buildings erected by the Gothic Arian king Theodoric in Ravenna around 500, the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo and the Arian Baptistery. Both contain sumptuous mosaics from their original Gothic Arian phase, supplemented by later orthodox work added after the Byzantine conquest. For an eye untrained in the niceties of art history, nothing in the Arian works distinguished them from their later counterparts. They look like exactly the kind of lavishly funded pious art we would expect from the period, regardless of theological precision.

We can only speculate what Christianity would look like if it rested on Arian foundations. But perhaps we don’t have to look far to find an answer. Every two years, Ligonier Ministries undertakes its State of Theology survey, the findings of which regularly demonstrate the gulf separating the actual beliefs of modern US Christians from the official doctrines of their churches. More than 65 percent agree at least somewhat with the purely Arian statement that “Jesus is the first and greatest being created by God.” (For whatever reason, Catholics seem to be the most happily Arian segment of American believers, but Protestants are not far behind.) On the other side of the equation, the share of believers strongly rejecting that statement, asserting their historical solidarity with Athanasius, is less than 20 percent.

What impact does that Arian triumph have on the lived behavior of those ordinary believers? Surely the answer is virtually none. It seems that for modern Christians, the Council of Nicaea was something that happened to other people.