Crossing religious boundaries at Groton

As a Muslim scholar teaching Indigenous history at an Episcopal boarding school, I have some learning—and unlearning—to do.

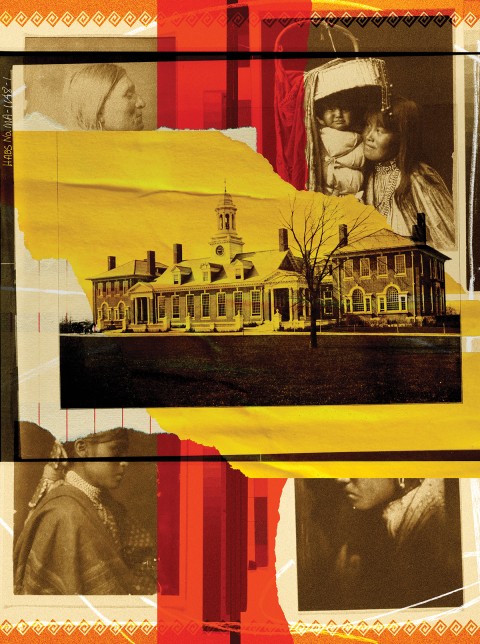

Groton School, in Massachusetts, circa 1903; portraits by photographer Edward S. Curtis, including Geronimo in the upper left (Century illustration | Source images: US Library of Congress)

The Nashua River marks the western border of the 480-acre campus of Groton School, established in 1884 on a site planned by Frederick Law Olmsted. Mount Watatic anchors the northwestern skyline. Mount Wachusett, the highest Massachusetts peak east of the Connecticut River, is visible from the bell tower of the high school’s imposing Gothic Revival chapel. But long before Wachusett was “New England’s most accessible ski resort,” and before the turn of the 20th century when the limestone of St. John’s Chapel rose above the treetops, and even as Henry David Thoreau eulogized Wachusett as “God’s croft,” these surroundings were home to flourishing Indigenous peoples with their own recreational activities, spiritual practices, and profound connections to the land.

European settlers established the Groton Plantation in 1655 along a preexisting Indigenous trail, and the settlement functioned as a trading post for exchange with the Nashaway people. For a time, the Nashua River formed a contentious boundary between White and Indian territory; a stone on the edge of Groton School’s campus memorializes John Davis, “killed by Indians at his door” in 1704. Residents of the commonwealth eventually annexed all the territory in the wider region, apart from four acres—stewarded to this day by the Hassanamisco Nipmuc Band. And despite the vibrant presence of multiple federally recognized Wampanoag tribes in Massachusetts, the Nipmuc are the sole state-recognized tribe. (Federal recognition is withheld based on Nipmuc “blood quantum” not meeting the exacting threshold specified by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.)

Though our geography and place names attest to the presence of Indigenous peoples, the narratives we offer ourselves often do not. But should they?