Beauty from ugliness on the US-Mexico border

Presbyterian border ministry in Douglas, Arizona, and Agua Prieta, Sonora

There is a stark beauty in the natural flora of the Sonoran Desert. Majestic saguaros, upholding their tall arms, are universally recognized emblems of the Southwest. All around them, similarly arrayed in dusty green tones for most of the year, are other desert-adapted succulents: prickly pear, cholla, ocotillo, paloverde.

But there is a stark ugliness of human making that greets a traveler to any of the cities along the border: a 20-foot-high barrier made of rusted steel pylons spaced a few inches apart. Birds and lizards and rabbits can pass through, but nothing larger.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

These sections of the border wall were built near each crossing in the 1990s. They became even more hideous, and more threatening, with the installation in 2019 of coils of concertina wire, stretched in rows in some sections from the top down to the ground. They were installed by National Guard troops, whose deployment in response to a nonexistent emergency angered local residents. The razor-studded wire poses little threat to crossers of the wall: they only need to carry an extra strip of carpet if they throw a tall ladder over the wall at night. (Hardly anyone crosses like this anyway, except in the imagination of politicians in distant cities.) Children and dogs who venture too close to the American side, however, risk having their flesh ripped open.

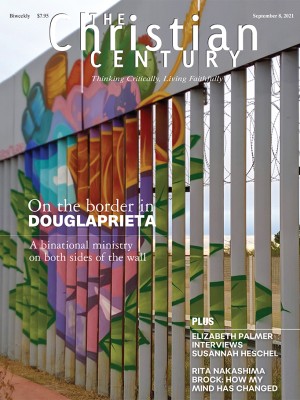

But on the Mexican side, the wall between Douglas, Arizona, and Agua Prieta, Sonora, has been utterly transformed from an ugly barrier to a colorful outdoor gallery, bearing images and words of hope and solidarity. The wall art project was launched about three years ago by residents of both cities, using bright acrylic paints that can withstand the brutal southwestern sun. Each image requires meticulous planning to span the gaps between the rectangular pylons. Some feature the flora and fauna of the desert: cactus, lizards, birds, and mythical creatures. Many give voice to a call for freedom and for affirmation of our common humanity, by depicting birds in flight, horses at the gallop, and butterflies flitting over and through the wall. A gaily colored bouquet of flowers bears the inscription “Amor sin fronteras” (“Love without borders”).

For more than 35 years, the Presbyterian Church on both sides of the border has assisted residents who seek both to create beauty and to counteract the forces of death and oppression. Presbyterians recently gathered to celebrate this work at a place that locals call “DouglaPrieta.”

Frontera de Cristo, a binational ministry, was launched here in 1984 to bring congregations together and provide needed services. Today it is one of five regional organizations that are part of the Presbyterian Border Region Outreach, supported by the Presbyterian Church (USA).

As recently as the 1960s, older residents remember, the border between Douglas and Agua Prieta was little more than a line on a map, wide open to people and animals alike. Both towns were then thriving centers of the copper mining industry. The 1980s brought renewed conflict between unions and the Phelps Dodge mining corporation, controversy over new limits on noxious emissions, and then the closing of the Douglas smelter, taking away most of the jobs in both cities. At the same time, the border was becoming increasingly militarized. It was then marked by barbed-wire fences, and immigration officials were demanding documents at the crossing points.

By the 1990s, would-be migrants all along the US-Mexico border were turned back immediately when they crossed through the ports of entry and deported swiftly if caught north of the border. Those who were seeking to escape poverty and violence in their home countries shifted from the major cities to the more remote and inhospitable regions of the border, like the desert around DouglaPrieta.

Officially the policy was called “prevention through deterrence,” but more candid observers, and even some internal government reports, used a more accurate phrase: “deterrence through death.” In every city, including small cities such as Nogales and Douglas, high steel walls were erected. The only option remaining for those trying to find work or join family members in the United States was to venture into the desert, avoiding towns and roads. More than 10,000 sets of human remains have been found in the desert, attributed to attempts by migrants to cross the border. Experts believe this evidence of the loss of human life is just the tip of the iceberg.

Through all the peaks and valleys of border “crises,” real or imagined, one important perspective has been overlooked. “You have to understand: the border is not the United States, and it is not Mexico, but a third country,” Pastor Ramon García Sanchez told participants at the Presbyterian gathering. García was then the pastor of a Presbyterian church in Hermosillo, the state capital of Sonora. The United States has its laws, and Mexico has its laws, he said, but the laws of the border are different from both.

“The Bible calls us to be hospitable!” he insisted. “It is the story of migrants like Abraham, Moses, Joshua, and Paul. The law and the prophets teach us that we must do better,” he added. “This is a great and historic responsibility—not just to respond to the injustice that we see but to create space in this world for the kingdom that is coming.”

From the beginning the work of the Presbyterian border ministries has been a rapprochement between churches north and south, overcoming the tensions in mission work that once resulted in a ten-year moratorium on foreign missionaries, put in place in 1972. But the dream of shared ministry never died. Saul Tijerina had the vision of creating servant churches on the border that united the evangelical zeal of Mexican Presbyterians with the PCUSA’s passion for social justice. In 1984, when Amelia del Pozo began gathering a few others in her home for worship, Frontera de Cristo began its life as a worshiping community.

That seed blossomed into Iglesia Presbiteriana Lirio de los Valles (Lily of the Valley Presbyterian Church) in Agua Prieta, now a close partner with First Presbyterian Church of Douglas in support of Frontera de Cristo. Services offered by the binational group include a drug and alcohol rehabilitation center, a community center, and a health education and screening center. Together with other local churches, Frontera de Cristo has established a migrant resource center, located just beside the border gate, where meals, showers, and a safe children’s play area are provided. Lodging for migrants is provided in a shelter that was created 21 years ago by Holy Family Catholic Church and is now supported by churches in both cities. The churches also nurtured the establishment of a thriving coffee collective called Café Justo. Its café is a social center in Agua Prieta.

In the migrant shelter, called Centro de Atención al Migrante Exodus (Exodus Center for Assistance to Migrants), temporary housing is offered to those who have come to the border fleeing violence or persecution at home in Mexico or in Central America. Under international law, the United States is required to admit them provisionally, provide temporary housing, and schedule a hearing to assess their asylum applications. In June, the Biden administration officially ended the destructive “Remain in Mexico” policy, which denied asylum seekers these rights. Title 42, which prevented asylum seekers from entering the country during COVID, has been provisionally lifted for unaccompanied children.

Perla del Angel, a Mexican lawyer and human rights activist, works closely with the shelter. She told us that when Andrés Manuel López Obrador became Mexico’s president in 2018, he promised to reverse the harsh policies of his predecessor toward refugees from Central American violence who were flooding into Mexico and seeking refuge in the United States. Rather than return them to face violence or death at home, he said, Mexico should welcome them and help them on their journey. But that promise has not been fulfilled, and Mexican government policies today are harsher than before.

Government assistance for the CAME shelter ended in 2019, even as its services were needed more and more urgently. In April and May of 2020, Angel reported, 144 residents were crowded into a facility built for 40. In June Mexican National Guard troops arrived, intending to arrest and detain everyone in the shelter. Fortunately, she said, the shelter coordinator refused to allow them in or to provide names. “We are in a struggle—a struggle with weapons aimed at us—for rights and dignity,” she said. “Mexico is now doing the work of the United States, and it’s doing it very well, unfortunately.”

Over the last seven months more than a hundred people have come to the migrant resource center each day. The CAME shelter is now mostly receiving people who have been expelled from the United States. The migrants often arrive in very poor health, and aid workers say the amount of death at the border has increased dramatically. This year will be one of the most deadly years for migrants in history.

Asylum seekers and migrants who stop along their journey in Agua Prieta are frequent targets of coyotes and drug cartel thugs who threaten to harm or kill them if they do not pay for protection. Parents do not dare allow children out of their sight, fearing kidnapping and ransom demands. For their protection, volunteers trained by the Presbyterian Peace Fellowship or Christian Peacemaker Teams travel with them from the shelter to the border crossing and the resource center. Those who accompany come to Agua Prieta in pairs, usually for two-week rotations, knowing that their status as US citizens will deter predators.

Perhaps this is one of the most remarkable things about these border ministries, says Mark Adams of Frontera de Cristo. They have been able to adapt to the rapidly changing conditions at the border while maintaining their values of hospitality and welcome.

At the Presbyterian gathering we heard from individuals and families who are seeking to escape intolerable conditions at home and finding governmental doors slammed in their faces. A Cuban family who fled the island in April 2019 because of political and racial reprisals found a coyote who demanded $6,000 to help them cross from Nuevo Laredo into Laredo, Texas, but then at the last minute he said he would help only the father, not his wife or children. The family came to Agua Prieta in hopes of finding work here and applying for asylum, but neither hope has been fulfilled. “The Mexican system for processing refugees from other countries has collapsed completely,” Angel explained, “and there is a backlog of many years.”

One day we gathered on folding chairs outside the migrant resource center, behind the high fences and locked gates that keep the coyotes and drug dealers out. Standing just 50 feet from the port of entry that so few are permitted to pass through, Alison Harrington, pastor of Southside Presbyterian Church of Tucson, offered a meditation on the meaning of sanctuary, reflecting on the pioneering work of her congregation in launching the sanctuary movement in the United States decades ago. In our churches, she said, we create sacred spaces and demand that the state honor them. We harbor those at risk of violence and death until they can find a place of safety of their own. Across the United States today there are a thousand congregations committed to the “new underground railroad” for the victims of government-sponsored violence.

But perhaps we should think about sanctuary differently, Harrington said. Imagine that we are standing on the banks of the Nile, during Israel’s time of captivity in Egypt, and there is a baby in a rush basket in the reeds at our feet. Pharaoh’s daughter rescues the baby, and “I’ve always seen her as the hero of the story,” she said—the one who saves Moses. But that isn’t what the text tells us. The baby’s sister, Miriam, a servant in the royal household, and his mother, Jochebed, have already created a sanctuary for the child, a quiet place among the rushes, when Pharaoh’s daughter stumbles onto it and helps them raise Moses.

We must be as brave and as resourceful as Miriam and Jochebed, Harrington urged. As empire expands, sanctuary must expand, and every home and school and workplace must become a safe haven for those whom the powerful seek to destroy. “The child whom we save in our sanctuary,” she concluded, “will be our liberator, like Moses.”

On Sunday, we returned to the beautifully painted border wall for a worship service as our gathering drew to a close. Worship leaders included the Mexican and American coordinators of Frontera de Cristo, Jocabed Gallegos and Mark Adams; Mennonite pastor Saulo Padilla; Brazilian-American theologian Cláudio Carvalhaes; and Harrington.

Carvalhaes offered a closing meditation on passages from Ephesians and 1 Corinthians, on the theme of siding with the immigrants. We must be on their side, he said, because that is where God stands. “To take the side of the ones at the margin is to make them our homeland. All the separated children, all the children now in cages, they are the homeland of my heart. What keeps us going is the love of God for the immigrants—our love of God by loving the immigrants. They are the face of love; they are the face of God.”

When it was time for intercessory prayer, the gathered congregation moved forward and spread out all along the painted wall. We spoke our responses to each petition into the narrow spaces between the columns.

Standing at the barrier, both a symbol and a practical means of separation and exclusion, our prayers seemed to be amplified by the cold columns we grasped. We knew that our American government would not listen. Yet we clung to the hope that before long, the Lord will turn the hearts of the American people to doing justice and loving mercy.

Just a week before the gathering, a family of Mormon settlers had been murdered near Agua Prieta by a drug cartel. We must not forget their suffering, said Carvalhaes, nor that of the victims of police brutality in American cities, nor that of the many thousands whose remains have been found in the desert. But we must think of the examples of Moses and Job and Elijah: we must look at what is around us, and then listen for God’s word to us—and then it is time to “talk back to God.”

The writers of the Psalms complained bitterly about all that they suffered—and then they called on God to be their deliverer, a cry that is echoed by the oppressed in every age. “I form the light and create darkness,” God tells Isaiah (45:7). “The Lord has said he will dwell in a dark cloud,” says Solomon (2 Chron. 6:1). Only when we face the darkness that we are in, in both our countries, can we look for a source of light that will lead us forward.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “A third country.”