Alasdair MacIntyre retains his power to shock

Reading After Virtue as a student was a revelation. As his colleague, I continued to learn from him.

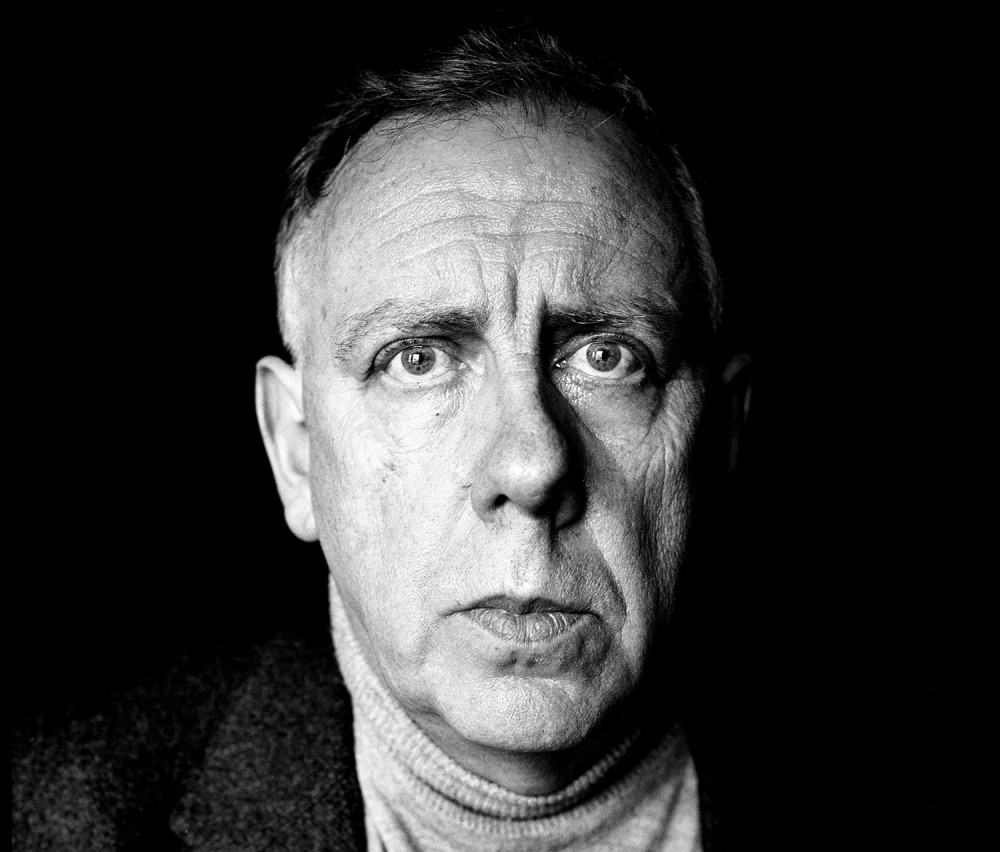

Philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre (Photo by Steve Pyke / Getty)

I still remember the first time I read Alasdair MacIntyre’s After Virtue. I was a graduate student in religious ethics at Yale, and someone, perhaps my advisor, suggested that I take a look at it. As I recall, it was recommended to me as a novelty, an interesting alternative to the analytic approach that dominated moral philosophy and, to a considerable extent, religious ethics as well. I certainly found that reading MacIntyre, who died last week, but I also found much more. To me, After Virtue had the force of a revelation. It opened up the possibility of a different way of studying and thinking about ethics, whether secular or religious: a discourse dominated by historically embedded conceptions of the good, grounded in ideals of honor, integrity, and, of course, virtue.

To a young aspiring scholar formed in the dry ascetical discourse of 20th-century moral philosophy, this made for exhilarating reading. I remember going to my professors, brimming over with new possibilities, ready to direct my whole doctoral program towards a study of moral traditions. They calmed me down and cautioned me against moving too quickly into this new approach. And I took their advice, but only up to a point. By the end of my graduate program I had begun to distance myself from some elements of MacIntyre’s program. I found that I was not entirely persuaded by his critique of the Enlightenment understanding of rationality, or perhaps I should say that I began to give more weight to the continuities between pre-modern and Enlightenment conceptions of rationality than MacIntyre did. Nonetheless, by that point he had already shaped my approach to the discipline of theological ethics—and to moral reflection more generally—in profound ways. He showed me the value of looking at a moral concept or debate in light of its historical and social context, and from that point it was impossible for me to see these things any other way.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I have spent some time describing my first reactions to After Virtue, because, as I soon learned, these were not just my reactions. It was one of those books that became a touchstone for a whole generation of young scholars, because it opened up a new, promising way of approaching a familiar subject. We had been trained to think in terms of abstractions, principles, and logical arguments. Religious ethics, too, generally emphasized abstraction over the concrete particularities of experience and belief. MacIntyre challenged this whole way of viewing the field, in the most uncompromising terms.

Within the field of religious ethics, many of us were eager for just this kind of message. We had been excited by the writings of Stanley Hauerwas, whose work was, from the beginning, resolutely theological, grounded in the particularities of the Christian tradition and above all centered on the person and work of Jesus Christ. MacIntyre was therefore not the first to suggest to us that the field of religious ethics might be due for an overhaul (although Hauerwas himself was inspired by MacIntyre’s work from a very early stage of his own career). But he brought new ideas and new ways of thinking about our field, complementary to Hauerwas’s approach and yet distinctive. Hauerwas was a Christian theologian whose work focused on theological ethics; MacIntyre was a philosopher sympathetic to theology, but he did not attempt to do theology himself. Each offered something of value to those of us working in religious ethics, or as we now say, theological ethics. And each one retains his power to shock, to open up possibilities for new ways of thinking about the moral life and our attempts to reflect seriously on what it means to be good or faithful.

Thanks to the title of his most famous book, MacIntyre is often referred to as a virtue ethicist. But that is not how he thought of himself, although he did do important work in this area. In my opinion, his primary contribution lies elsewhere, in his work on what he called “tradition-guided inquiry” and the possibilities for rational thought in a world of particularities. He offers a detailed account of this in Whose Justice? Which Rationality?, grounding his analysis in a close reading of Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas, and Hume. Similarly, in Three Rival Versions of Moral Inquiry, he argues that Aquinas's integration of the seemingly incompatible perspectives of Aristotle and Augustine laid the foundation for a successful tradition of inquiry, with real staying power even in the face of the challenges of modernity.

MacIntyre’s return to tradition and social particularity was shockingly new to my peers and me, but as we came to see, similar claims had been made many times before, from many different intellectual quarters. Still, MacIntyre was not content to shock us out of complacency; he went on to take up the hard challenge of reclaiming rationality, or perhaps I should say, offering an ideal of rationality consistent with the tradition-bound nature of all inquiry.

He did so by working out an account of how traditions develop, identify inadequacies, and correct themselves, in the process generating notions of intellectual adequacy and error. These notions can then be applied to other traditions of inquiry, and to one’s own tradition, seen in relation to these others. Through comparison, facilitated through a kind of two-way translation, the other tradition may appear as lacking in its ability to address fundamental questions. But it may not—indeed, it may well transcend one’s own tradition in its explanatory power. In this way, tradition-grounded inquiry can be self-critical, even to the point of abandoning one’s original starting points to embrace a better alternative. MacIntyre’s work in After Virtue is greatly influential, but his later work on tradition and inquiry represents something much more difficult and valuable: real progress on seemingly intractable philosophical difficulties.

So far, I have focused on MacIntyre’s liberating effects on those of us working in the field of religious or theological ethics. I don’t think it is an exaggeration to say that he, together with Hauerwas and a few others, created the field of theological ethics as it existed in the 1980s and 90s, or at least he helped to create the conditions in which theological ethics could emerge. At the same time, he also contributed directly to theology and theological ethics, in ways that clearly reflected his overall philosophical project yet also went beyond it.

By the early 1980s, MacIntyre was a practicing Catholic, and from the mid 80s onward Catholicism clearly shaped his intellectual work. He also wrote and spoke on explicitly theological topics, including the meaning of human dignity as understood within the Catholic tradition, the nature and limits of God’s foreknowledge, and the distinctive character of authority within the church.

One of my personal favorites among his theological works is his lecture, “Catholic instead of what?” delivered in 2019 at Notre Dame. In this lecture, he began by observing that Catholics are defined by what they believe, assertions grounded in doctrine, but also by what they do not believe, claims which to a considerable extent are rooted in the contingencies of society. For today’s Catholics, these include scientific naturalism and irredeemable tragedy, the first because it denies even the possibility of nonmaterial causes and the second because it forecloses any kind of hope. To which I can only say, “Hear, hear!”

I was privileged to be MacIntyre’s colleague twice, at Vanderbilt and at Notre Dame. I cannot say that I ever knew him well. But over the years I got to know him a little better, mostly thanks to his efforts to reach out to me. In my dissertation, I had ventured some criticisms of his work, and he went over these with me, without the least hint of rancor or condescension. He extended the same kindness to me every time I published anything on his work: he sought me out, sat down with me, and went through everything, in a spirit of a genuine investment in the issues. Sometimes he agreed with me, often he did not, but in any case what mattered to him were the issues themselves. I don’t believe I have ever known an academic with less investment in his own ego.

I learned so much from MacIntyre, as a scholar, a philosopher, and a human being, and I believe that I will continue to learn from him as long as I am doing this work. And again, I am not alone in this. A whole generation of scholars is in his debt.

This article was edited on May 28 to add some additional material.