Lent beckons like an open door

For 40 days, we contend with our mortality so that we might know what it means to live.

“The first door opened and I walked through.”

This early line in Ann Patchett’s title essay of her new collection, These Precious Days, is its own doorway into a beautiful reflection on friendship in the time of coronavirus. Serendipitous choices and Tom Hanks feature prominently at the beginning, and what unfolds is a remarkable story of kindness and courage. Patchett recounts the experience of coming to know, mostly through email correspondence, a California artist named Sooki, who comes to stay with Patchett and her physician-pilot husband in their Nashville home. Sooki is in desperate need of treatment for pancreatic cancer. Without much success, she has been a patient at several elite medical facilities around the country. It turns out that the hospital where Patchett’s husband works, five minutes from their house, is running a clinical trial on a promising new therapy. It also turns out that Patchett has a habit of regularly welcoming an eclectic collection of friends and acquaintances to take up residence in their home.

Hospitality, the awkwardness of being a host and a houseguest, the fear and uncertainty that come with a cancer diagnosis, the anxiety that accompanies the onset of pandemic, and the small, ordinary ways human beings make community in the midst of such contingencies—these are the essay’s themes and threads. Patchett traces them all in ways that honor the mystery of being human and of being in relationship as creatures with both good intentions and confused motives who often fail to say what we mean, or even to know what we mean.

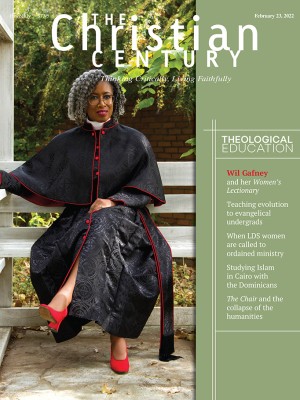

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

“The first door opened and I walked through.” The metaphor is useful for all kinds of thresholds we encounter, whether welcome or not. The latter often cannot be refused or retreated from—an illness like Sooki’s or any number of the heartbreaks and tragedies that visit us unbidden. With these we may not so much walk through the open door as stumble through it, bruised and wrecked, fearful of the unknown that awaits us on the other side. Two years into the pandemic, we have all walked through many doors, crossed many thresholds, and had the common experience—even if the circumstances are always singular—of work, home, school, church, and other social spaces being irrevocably altered, some unrecognizably so, and ourselves profoundly changed, too.

To enter the season of Lent is to walk through an open door. Corporately we ritualize the traversing with the imposition of ashes—the black, sooty smudge a sign that death is the last threshold we will cross. In the liturgy we are asked to meditate on that truth. Remember you are dust and to dust you shall return. The sojourn in Lent, if we are able to abide it, is 40 days of contending with our mortality such that we might come to know more fully what it means to live. It isn’t a way station so much as a working ranch: space and time to labor on the hard and necessary thing, to “keep death daily before our eyes,” as St. Benedict counsels.

The ancient practice of memento mori (“remember you must die”) is part of many cultural and religious traditions and has recently drawn renewed attention through the work of Sr. Theresa Aletheia Noble, one of the #MediaNuns, who keeps a ceramic skull from a Halloween shop on her desk at all times. She and others insist that the aim of the spiritual exercises associated with memento mori is not a morbid obsession with death but awareness of the graces that sustain our lives—graces we have been given and those we have granted others or withheld from them. In Lent, with gratitude and penitence, we follow Jesus to the Place of the Skull where death—his and our own—is transformed.

While crossing the threshold into a meaningful Lenten observance may be an individual act, once there we discover—or at least we have the hope of discovering, as Ann and Sooki did—that keeping company with others in our shared finitude can be a doorway into life, into presence, into the sustaining graces that make our lives beautiful. We are made for communion, though much about our formation gives the lie to this, schooled as we are to prize and strive for self-sufficiency. When we struggle in the shadows alone in Lent or at any other time, we feel the betrayal of that formation. It can be difficult, as James Baldwin once wrote, “to say Yes to life.” But when we find the strength to make our vulnerabilities visible to another who sees us and desires our good, when we can acknowledge what has wounded us, what terrifies us, we are given the freedom, finally, as Patchett exquisitely puts it, “to lay down the burden of [our] own vigilance.”

“The first door opened and I walked through.” The good news is that we do not have to cross the threshold alone. Friends in their kindness give us courage, divine grace freely poured out. And when we enter into Easter, mindful still of mortality and loss and the scars we bear, we remember also that nowhere in our fear and brokenness has Christ not also been. Gospel enough for this day and all our precious days.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Lent beckons like an open door.”