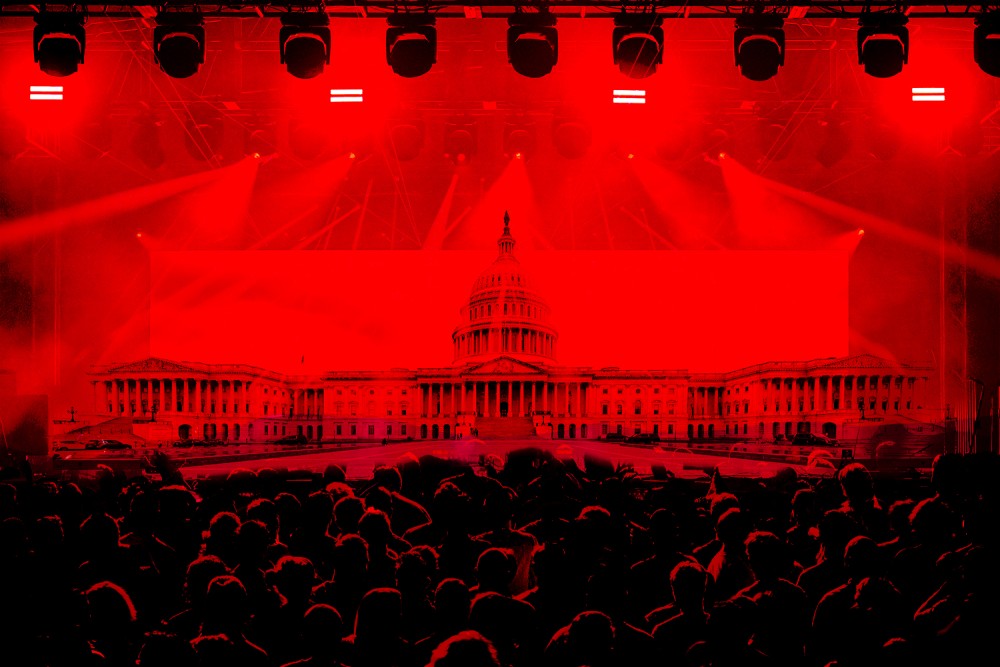

The politics of performance

In the Trump era, the narrative around legislative efforts seems to matter a lot more than the actual results.

Century illustration

After the Uvalde school shooting in 2022, Congress enacted a bipartisan law, to great fanfare, that included $1 billion for mental health programs in schools. This spring, the Trump administration zeroed out this budget line. According to The New York Times, no GOP member has offered a single public word in protest.

In July, Congress narrowly enacted President Trump’s tax law. It’s a hit parade of destructive provisions: tax relief for the rich, draconian cuts to Medicaid and food assistance, $3 trillion in new federal debt, and more. It breaks promises Trump and other Republicans made, and many of its provisions will disproportionately harm people in red states. Multiple GOP members offered sharp criticisms of the bill. Then all but four of them voted for it anyway.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

These events point not just to Trump’s domination of his party but also to a broader problem. Because most voters pay more attention to political tit-for-tat than to substance, politicians have long emphasized the performance of useful narratives—their political value is much greater than just as a means to a public policy end. In the Trump era, it’s grown worse: the performance now seems to be the entire point.

Three years ago, GOP members performed the narrative of addressing school shootings. This summer, it was about supporting a “big, beautiful bill” to help Americans. The first story’s connection to policy realities was short-lived; the second lacked any connection from the start. And once the news cycle moves on, legislators can hardly be bothered even to pretend to care about the results. The results were never the point.

“Ruling performers,” writes Stephen Marche in The Atlantic, “serve the narrative needs of their fans first and foremost.” In the wake of a tragedy like Uvalde, fans of whatever party want to see officials do something about it. When Trump wants a law passed, his fans want to see Republicans fall in line. In both cases, this initial narrative matters more to people than whatever comes later. Neil Postman argued in 1985 that TV had transformed politics from rational argument to entertainment. Forty years and several media revolutions later, Marche’s observation is that in whatever medium, even ostensibly rational argument is really about performing a narrative—because that’s what people are focused on. “In a politics determined by performance,” writes Marche, “outcomes are epilogues that nobody reads.”

Voters have long been inattentive to policy details; in recent years they’ve also been actively disinformed about them. But the problem of a politics of performance isn’t just about information. People genuinely care about the political narratives they see performed, because those narratives speak deeply to questions of culture and identity. Even understanding the policy implications doesn’t necessarily make people care about them, at least not in the same visceral way.

Fighting disinformation is difficult, discouraging work. Correcting the record on policy can feel like screaming into the void. But we who seek the common good also need to perform different stories from the dominant ones in our politics. Truthful, lifegiving stories. Stories about culture and identity at their most openhearted and generous, not their most insular and fearful. Stories of integrity, not empty promises.

This too is an enormous task. It’s also one that a lot of Americans are already doing and that others know how to do. Artists, writers, and teachers perform stories. So do preachers. Our political life is dominated by the performance of narratives that eclipse the real consequences for human welfare. To combat this, we need better stories.