Peter Spier’s picture books praise the world

The Holocaust survivor’s response to suffering was to create joyful children’s books.

When I read to my two sons, I find myself marveling at the way they respond to good books. Their reaction is physical as much as mental. After a day of running and leaping, they climb into my lap at bedtime and almost instantly grow calm. Jittery limbs stop moving for the first time all day. Their breathing slows and deepens, and so does mine. We sink into a worn reading chair and travel into the world of a story.

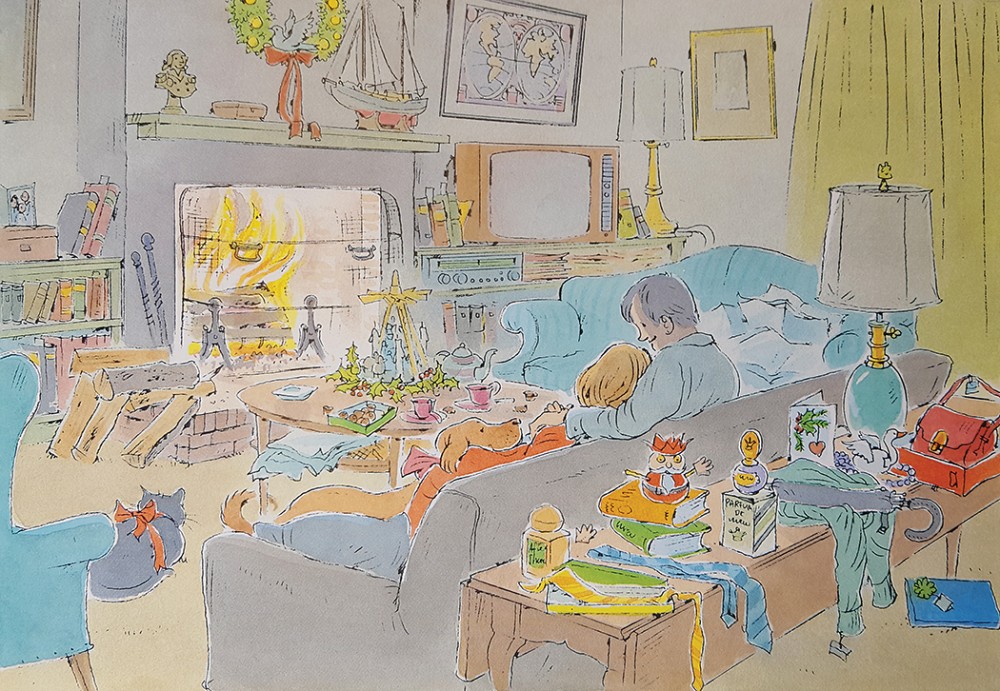

For a stretch of time when my son Samuel was three, each night he demanded that we read a particular book by the author and illustrator Peter Spier. It was a book about Christmas, but it was popular with Sam year-round. Peter Spier’s Christmas! follows three children and their parents as they shop, decorate, bake, wrap, sing, wait, and finally tear open gifts on Christmas morning in a frenzy of delight. At night the children lug armfuls of new toys up to bed and fall asleep in a room strewn with books, a tricycle, and a locomotive the size of a toddler. Sam took it all in with wide, hungry eyes.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

We have several of Spier’s books, and they all share his warmhearted perspective on his subjects, whether a circus, a farmer’s market, or children playing in a rain-soaked garden. His intricate ink-and-watercolor style holds up especially well to repeat readings, offering intriguing details like cookie crumbs beneath a table, an ornament broken by the youngest child, and a cat picking at the turkey carcass after the holiday feast. Spier seems to take particular delight in the sheer amount of mess that children, a cat, and a dog can make over a few weeks in December.

Beneath the clutter celebrated in the Christmas story lies a deeply ordered world. All the characters in the village have their place: the shopkeepers, the churchgoers, the postman, the Salvation Army bell-ringer. The parents have a happy marriage, the father provides a stable income, and the mother orchestrates shopping trips and craft projects. On Christmas day the grandparents arrive healthy and hale, the turkey turns out golden and moist, and the downy snow falls on cue. It’s a comforting, nostalgic vision.

Spier, who died last year at age 89, created more than 50 titles, many of which are still in print. After an apprenticeship illustrating the books of others, he gained attention in 1961 for The Fox Went Out on a Chilly Night, which adapts an old English folk song to portray a fox dashing through the Vermont countryside. The Erie Canal established him as an affectionate chronicler of the pastoral Northeast, following mule-drawn barges through hamlets and rolling hill country. We the People and The Star-Spangled Banner commemorate the wisdom of the nation’s founders. His retelling of the biblical story of the flood in Noah’s Ark won the 1978 Caldecott Medal for best picture book for children. He was a National Book Award finalist in 1980 for People, which uses hundreds of small images to convey the diversity of people around the world, including their variety of skin colors, hairstyles, clothing, jewelry, housing, games, pets, foods, and religions.

People’s celebration of cultural diversity is an exception among his books, which typically inhabit the world of colonial America and pastoral New England. It’s impossible to miss the overwhelming whiteness of Spier’s books, particularly in the Christmas book, which excludes anyone who doesn’t look like a WASPy upper-middle-class New Englander. An early review of it in School Library Journal noted the uniform whiteness and affluence of the characters.

As I considered Spier’s work, I found other faults. His patriotic books omit slaves and Native Americans and valorize soldiers in a way I don’t want for my sons. In People, a conspicuous number of the nonwhite figures are portrayed with loincloths, spears, and bone jewelry. Amazonian shamans and Bantu tribespeople seem to stand in for entire continents.

Though I felt like a Scrooge for noticing it, the Christmas book is a kind of celebration of materialism. Beginning with the title page, which displays a full-spread tableau of a festive shopping mall, the story is an ode to unchecked consumerism. That cheerful Christmas clutter is pretty much all disposable—wrapping paper, plastic toys, food scraps, a single-use fir tree. The children long for their presents and receive a pile of them, the ritual presented as a satisfying process of wish fulfillment. Later scenes show more rituals of consumption—a department store with a crowded returns counter and postholiday markdowns. There’s no sense that this kind of celebration is tremendously wasteful, and no hint that a festival with less stuff might be more meaningful.

I assumed that the author of such a rosy vision of American life must have had his own idyllic American childhood and was probably himself a WASP from New England. It turns out that Spier did spend most of his adult life in Shoreham, New York, a quaint, upscale town on Long Island. He and his wife, Kathryn, raised two children there, and he spent his free time building model ships and sailing on Long Island Sound. None of that surprised me.

But just about everything else I learned about him did. Spier wasn’t a WASP but Jewish, born in Amsterdam in 1927. He grew up in the town of Broek in Waterland with his parents and a younger brother and sister. His father, Jo Spier, was a successful illustrator at the newspaper De Telegraaf until he was fired after the German occupation of the Netherlands in 1940. Jo Spier was later arrested for creating a satirical drawing of Hitler, according to records from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The family was briefly detained in the parsonage of a Christian Reformed church in Doetinchem. When Peter was 16, they were deported to Theresienstadt, a Nazi concentration camp in German-occupied Czechoslovakia.

Theresienstadt was a transit camp, a place where Jews were held before being sent to death camps or forced-labor camps. It also served a propaganda role for the Germans, who presented the camp as a spa where Jews were being protected.

After a beautification project involving gardens, fresh paint, and renovated barracks, the Germans allowed the International Red Cross to visit the camp in June 1944. Several resident artists, including Jo Spier, were ordered to create illustrations to show the visitors. According to Glenn Sujo’s book Legacies of Silence: The Visual Arts and Holocaust Memory, the elder Spier produced 18 picturesque lithographs showing the camp’s shops, coffeehouse, children’s theater, bakery, and neatly ordered gardens. In Sujo’s words, Jo Spier’s artworks conveyed “the false impression that here was a well-ordered society, a resort for Jews, sheltered from events outside.”

The camp had an extensive cultural life. Musicians, actors, and scholars gave lectures and performances. There was a large lending library and a studio for artists. A drawing of the studio by Leo Haas shows artists gathered around a table, with a boy peering over a man’s shoulder. Sujo wonders if the boy in the drawing could be a young Peter Spier, watching his father work.

Ninety percent of those who passed through Theresienstadt were killed in death camps. The Spier family was among the survivors. The family returned to Amsterdam in 1945. Peter attended the Rijksakademie, the national art school. He was drafted by the Royal Dutch Navy and traveled to South America and the Caribbean, feeding his lifelong fascination with sailing and ships. He worked in Paris as a correspondent for the Dutch magazine Elsevier’s Weekly. In 1953, when he was 26, he emigrated with his family to the United States.

In light of this history, my multicultural critique of Spier’s work felt foolish. Surely Spier knew more about ethnic hatred than I ever would; what could I add by criticizing the racial representation of his books? If his depictions of rural Americana struck me as overly fond, this country offered his family a safe haven after an ordeal I can only imagine. I’ve spent much of my life taking civic institutions for granted; he saw firsthand what happens when they collapse.

I thought again about my critique of all the clutter in the Christmas book and of his celebration of the shopping mall, the grocery store, the crowded church, and the family’s house, all overflowing with colorful stuff. Spier seems to revel in it all, perhaps because it’s so much fun to draw and paint. When the kids climb into bed at the end of Christmas Day, their sheets spilling over with toys, dirty socks, and a rumpled bathrobe, you can sense the artist’s pleasure.

Spier never spoke publicly about his time during the war. He never addressed it directly in his books, which, after all, are for children. But there are a few oblique references in his work.

In People, one image depicts a mass rally draped with red and black flags, with men in brown shirts and armbands. Adults if not kids will connect the scene to Nazi Germany. Nearby, another image shows military commanders with stern faces reading a battle map, backed by tanks. “Some people, but very few, are mighty and powerful,” the text reads, “although most of us are not mighty at all.”

The determined expressions of the generals caught my son’s attention, and I struggled to know what to say about them. It’s telling that these are small images, each no more than a quarter of a page. They receive a brief moment in a parade of more creative people and activities: fortune tellers, deep-sea divers, snake charmers, cricket matches, rodeos. Wars and terrible leaders are part of life, Spier seems to be telling children, but not the most important parts.

There is little published biography about Spier, and even less about his time during the war. A 1978 profile by Janet D. Cheney for the children’s literature periodical Horn Book includes a curious quote from Spier:

There is something special about books. Most things in history, no matter how ghastly or cruel, are forgotten in the end, but people still talk with special horror about the burning of the Alexandrian Library and about book-burning by dictators or during the Inquisition. Murders are forgotten, but the eradication of ideas, of books, is not.

In all his published work and recorded comments, it’s the closest thing to a reference to his time at Theresienstadt. Creating art, he suggests, is a response to the problem of violence. The effect is to point attention back to his books.

The biblical story of the great flood, with its horrific destruction, provides an unstated parallel to the Holocaust. Spier explained in his 1978 Caldecott Medal acceptance speech that he grew interested in retelling the story when he reviewed the many existing children’s books about Noah’s ark. They all presented the story as a “joyous sun-filled Caribbean cruise.” None of them depicted Noah shoveling manure. He decided there was room for one more book.

Spier’s style suits the story well. His images are packed with detail, but not in the static, symmetrical manner of architectural studies like David Macaulay’s Castle. Spier’s fluid, curving lines nearly always suggest movement. His skies are alive with birds and windy gusts.

As Noah and his family hammer and haul and shovel and labor, they display the industrious energy that so often marks human figures in Spier’s books. The animals clamber and jostle. The images play with the logical absurdity of fitting two of every living creature onto a boat. Hippos share a swimming tank with seals and ducks. Monkeys cling to rafters alongside fruit bats. As a weary Noah sits by candlelight one night, cats, dogs, cows, and mice intrude upon his loneliness. After the flood, the male and female rabbits emerge from the ark trailing 18 giddy offspring. The success of the visual story is that you can hear and smell those living, breathing, defecating, procreating creatures crammed together.

The children’s author Katherine Paterson praised Noah’s Ark, saying:

Theodore Gill has said, “The artist is the one who gives form to difficult visions.” This statement comes alive for me when I pore over Peter Spier’s Noah’s Ark. The difficult vision is not the destruction of the world. We’ve had too much practice imagining that. The difficult vision which Mr. Spier has given form to is that in the midst of the destruction, as well as beyond it, there is life and humor and caring along with a lot of manure shoveling. For me those final few words “and he planted a vineyard” ring with the same joy as “he found his supper waiting for him and it was still warm.”

Those last words are the ending of Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, another children’s book with colorful creatures, a fantastical journey, and an ending that is both reassuring and still shadowed by danger.

There is a recent trend in children’s literature to deal more directly with social problems. Spier chose to do something quite different in celebrating the created and human-made world. I don’t think that’s avoiding darkness. His approach, consciously or not, was to work in the mode of praise, affirming the goodness of the world by rendering it skillfully, with humor and delight. The body of work that emerged forms a stunning response to the nihilism of the Holocaust.

Children’s stories are deadly serious, even when they’re funny. They teach children how the world works, how families work, how to treat others, how to respond to danger. The cozy world of Peter Spier’s Christmas! teaches tenderness in the ways family members and neighbors exchange gifts and hang decorations for the pleasure of others.

Spier’s art involves omissions, as all art must. That’s the function of a frame. What I appreciate most about his work is the way it treats praise as a craft, something that can be done poorly or well. Spier spoke in his Caldecott Medal speech about a draft of Noah’s Ark that included a scene of all the animals not selected for the ark, “hundreds of drowned animals awash in the waves, some with their heads down, others with their legs sticking up in the air.” Ultimately, he decided the scene was too grisly for children and left it out. “I always find it difficult to determine where that invisible line, the border between good taste and bad, runs,” he said.

My wife, Hannah, who grew up reading Peter Spier’s Christmas!, pointed out to me the way that Spier uses color to control the emotional register of the narrative. Frenetic scenes are balanced by moments of calm. As the family steps outside to admire their lights from the sidewalk, the indoor yellows, oranges, and pinks give way to the deep blue hues of moonlight on snow. The story hinges on a sweeping landscape view late on Christmas Eve, the town asleep in snow-blanketed houses, resting before the festivities of the next day.

For me, the most striking images are three near the very end. The first shows the kitchen after the Christmas feast, the counters heaped with dishes and soiled napkins. In the next panel, the husband and wife stand at the sink washing and drying, laboring, but together. Finally, with their kids asleep upstairs, they collapse on the sofa by the fireplace. The room is still a mess of half-eaten chocolates, scattered gifts, and a tumbled stack of firewood. The dog noses for a spot on the sofa. Nothing in the scene guarantees that the peaceful moment will last, that danger is not approaching outside the window. The sense of safety may well be an illusion. But the moment is worth noticing. And it’s worth learning how to render such moments in artwork, story, or simply in quiet prayers. In attending to them, we learn to see them more clearly.

To read to young children is a holy thing—even when they’re fidgety. They respond to stories with utter trust, their bodies relaxing and their minds transported. That trust seems reckless in a world so dangerous. And of course it is. Peter Spier understood that trust as a gift, and he responded with page after page of creatures as colorful and intricate as life itself. After everything that he had seen, he saw the world as a place to explore and celebrate—and he invited his readers to do the same.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “In praise of the world.”