As a pastor, it’s my job to pay attention

In the Mennonite tradition, we are all priests. But I still have a particular role to play.

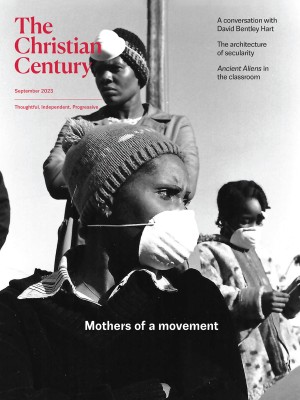

Century illustration

“Ordination in the Mennonite church is awkward,” I recently told a woman discerning ordination. “It is strange to be a priest among priests.” My ordination confers few privileges and little standing. Mennonites are priests by nature of our baptism, and any other priest-by-baptism can preside over communion and preach—each according to their gift and calling within the body of the church.

For centuries, Mennonite pastors were chosen by lot or election from within their community. They pastored for a season before returning to other labors. More often than not, these men tacked the responsibilities of preaching and accountability onto their work of farming or carpentry or smelting. Early Anabaptists derived this practice from Acts, where the inner circle of Jesus’ followers is replenished after the betrayal of Judas.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

There’s an old story that in the 16th century, Anabaptists chose the least essential person in the community as their pastor. That way, when persecution came and the pastor was inevitably killed, the community wouldn’t lose an essential service like a cobbler or a mason. While I can’t establish the veracity of this story, I attend to its wisdom.

Even as Mennonites like me receive education in seminaries and are called by congregations in other places, I keep the vulnerability of my pastoral role close to me. I am nonessential personnel in the strictest sense, and while I’m sure my church would bristle at this description, it’s a truth that shapes my pastoral identity. Raleigh Mennonite Church has all the gifts it needs to proclaim the gospel in word and deed, to love one another and the world, to be the body of Jesus.

My congregation tasks me not with filling in the gaps for what they cannot do but instead with paying attention. I remember one Sunday when the lectionary sent me to the Gospel of Matthew, where Jesus encourages us to “consider the birds” (6:26). I took him at his word and spent time that week paying attention to birds. By the end of the week, I realized this exercise simply shifted the object of my regard. I pay attention for a living. To attend is to heed and to stretch. We stretch ourselves beyond what is readily perceptible. We await. We expect. There is something around the corner, and if we hold still and do not startle it, we might be in for a discovery.

So it is for the pastoral role. I collect stories, and I take out the trash when the task is overlooked. I give my unguarded curiosity to scripture and see what comes of it. I listen in prayer, stretching myself to heed what is hidden behind the noise and rush of the day. I remember when I first noticed Debbie’s pastoral gift as she offered empathic listening and calm hope to her fellow workers in the grocery department she managed. I told her what I noticed. This past spring, she graduated from seminary.

I often pay attention to what might be lost in the shuffle of survival. Who is struggling to pay their rent? Who is missing from worship for several weeks? Who has gone quiet in our meetings to discern God’s direction for our community? Who hasn’t heard recently that we are grateful that they lead worship or run our AV equipment? Who is angry and needs to be asked why? The work of attending fills my days. I have little time left to worry about the church’s survival or relevance.

The discipline of paying attention, and my attending anticlericalism, extend into works of justice and peace. As my attentiveness has grown, I’ve shied away from clergy-led organizing in favor of what the Black Lives Matter movement calls “leader-full movements.” I am already unrecognizable as a clergyperson in public gatherings. I have no stole, and I wear no collar or cassock. And while I’m often told that my visibility as a clergyperson provides a public moral voice, I’m aware that all around me are people who have kept communities alive and children safe for decades at a time.

During the Moral Monday movement in North Carolina, a speaker at a podium asked clergy to lead a crowd of hundreds into the state capitol. As I joined him at the front, I noticed who I was walking past. I passed a Black elder, a woman who has steadfastly advocated for her community for decades. I passed a local churchwoman who raised her own children and then raised her neighborhood’s children and grandchildren. I passed teachers, a social worker, and an immigration lawyer. What moral voice could I project that they hadn’t already displayed with their lives?

I recognized these faces in the crowd, I knew their commitments and their faith, because my calling as a pastor is to pay attention to them. I’ve witnessed these people show up to city council meetings strategically planned at a time when those opposing a zoning ordinance could not get off work. I’ve watched them leave groceries on stoops and organize the cleanup of the historically Black cemetery. Their attentiveness taught me how poverty and power are masked. From them I learned how to see what is hidden from view.

One of the most tender stories from the Desert Fathers concerns what is possible when we attend to one another in this way. Some older men go to see Abba Poeman, and they ask what they should do if they see a brother fall asleep during divine worship. “Should we wake him up?” they inquire. “As for me,” Abba Poeman replies, “when I see a brother who is falling asleep during the Office, I lay his head on my knees and let him rest.”

Attentiveness stretches toward care. We are tired and need rest. We are full of love, waiting for embrace. Ministry stops, holds, attends to all of it, the place where God is found.