Why don’t the Gospels describe Jesus’ appearance?

Joan Taylor's top-notch scholarship reads like a detective thriller.

According to Jewish wisdom literature, “the making of many books is endless, and excessive devotion to books is wearying to the body.” The same could be said of visual representations of Judaism’s most controversial child: Jesus of Nazareth, or whatever one wishes to call that Jewish person from the Middle East who probably lived there 2,000 years ago, may have amassed a following, and whose disciples organized churches and scriptures around stories of him.

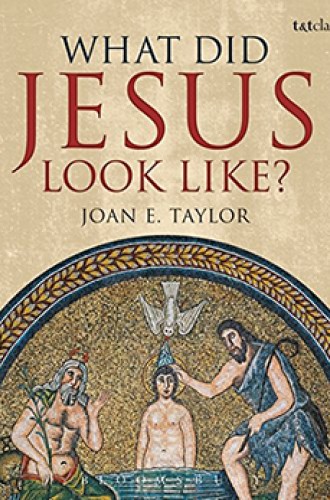

Although the original texts relating to Jesus disclosed very little about his physical appearance, images of the peasant preacher appeared a few hundred years after his death. In the two millennia since, millions upon millions have been produced and reproduced. They have become staple elements of a global visual culture ranging from the walls of opulent cathedrals to films projected onto stretched sheets in parts of the world where it’s a struggle to obtain clean water. While the teachings and words of Jesus may not be universally known, and are definitely not universally followed, it seems that images of him have become omnipresent.

Given the lack of original textual evidence, how did this imagery become manifest? Why did some images become popular and others fade into obscurity? How can Jesus’ face, body, clothes, and footwear be revealed? What do those visual features mean to Christians and non-Christians over the centuries and today?