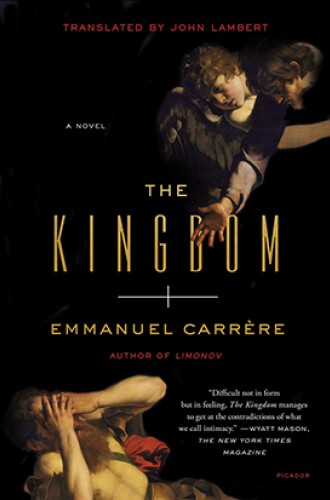

The rise and fall of Emmanuel Carrère’s faith

The Kingdom is a mess, but it refuses to be wholly dismissed.

The Kingdom arrives in the United States already coronated. It drew raves in translation last year from British reviewers, and the novelist-journalist-screenwriter-celebrity Emmanuel Carrère is an intellectual star in his native France. Carrère tells the story of his brief but intense time as a believing Christian 20 years ago, then maps that personal conversion (and later deconversion) onto the story of Christianity’s early centuries. Like that history, The Kingdom is a mess, one that refuses to be wholly embraced or dismissed.

Other reviewers have likened The Kingdom to a novel—in particular, the autofictions of Karl Ove Knausgaard and Chris Kraus, which mix personal confession and autobiography with long, essayistic digressions on ideas, people, or works of art by which the author remains transfixed. But aside from the opening and closing sections, Carrère puts his own story—distractingly—in service to the book’s informational content.

Most of The Kingdom resembles not a novel or autobiography but a highly engaging series of lectures, taught by the sort of shamelessly biased, engagingly sloppy, inappropriately digressive college teacher whose students love him (this type is usually a him) but who will never get tenure. His analogies and examples dazzle and sometimes blind; he is always ready with the kind of explanatory anachronism that a fully licensed expert knows too much to risk. He says Paul’s conversion is like Philip K. Dick’s famous mystical experience, and that Hellenic Jewish proselytes are like bourgeois Americans who dabble in Buddhism. Are these comparisons true? Are they helpful? They’re certainly memorable.