The remarkable life and martyrdom of Lin Zhao

As Chinese communism turned to violence, Zhao turned to Christ. Lian Xi tells her story in memorable fashion.

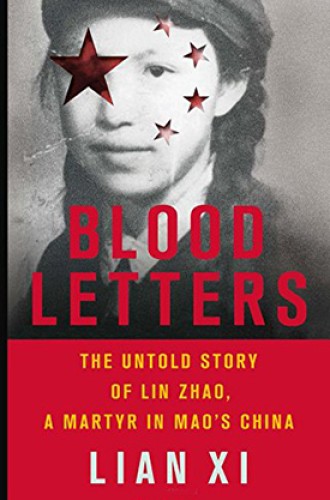

Almost exactly 50 years ago, with no fanfare, a 20-year prison sentence was altered to a death penalty, and the poet-dissident Lin Zhao immediately became a Christian martyr. Her story, as told by Lian Xi, is both remarkable and common. Blood Letters, carefully researched and timely, reveals the trajectory of a privileged girl who went from Christian to communist comrade to a Christian resister whose crime was being an “impenitent counterrevolutionary.” Even told poorly, this would be a remarkable story. Xi tells it in memorable fashion.

Behind the tale is an intriguing backstory. As Xi tells it, “In 2013, The Collected Writings of Lin Zhao . . . was privately printed. I was given a copy. It was a godsend.” Miraculously, in 1981, 13 years after her death, Lin Zhao’s case was reviewed by a judge, and she was posthumously declared innocent. The judge decided to release the secondary documents—those not dealing directly with the trial—which, it turns out, are a treasure trove of poetry, personal and editorial letters, and other writings. Many were written in her own blood, as she would prick her finger and collect the blood in a spoon. Xi pieced together the story through these many writings, interviews with those who knew Zhao, and an independent film titled Searching for Lin Zhao’s Soul, produced by Hu Jie (2004).

Zhao’s life is a mirror of China in the Maoist years. Like many young Christians, she was caught up in Mao’s vision of a new China, where land reform and proletarian rule would create something close to the community described in Acts 2. A passionate but sickly young woman, she got directly involved in land reform and sought to become a party member. She worked hard to please the Communist Party (and, by extension, to please “our dear Father” Mao).