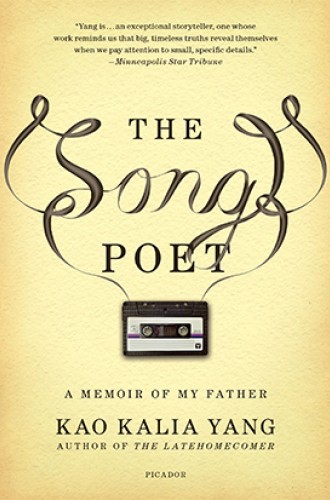

Refugee, poet, father

Kao Kalia Yang’s memoir of her family’s flight from Laos is devastating and lyrical.

Author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie wrote, “Nobody is ever just a refugee. Nobody is ever just a single thing.” Yet, it can be hard to uncover the humanity behind refugee narratives. Refugee stories are often written with the help of a translator or ghostwriter and, in the process of translation, they develop a quality of sameness.

Enter Kao Kalia Yang, among the most lyrical and eloquent memoirists of her generation. Unlike refugee memoirs that clunk along in the words of a second language or a ghostwriter, Yang’s stories reveal the intimacy of family with the literary skill of an MFA graduate. (She has a degree in creative nonfiction from Columbia.)

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Yang’s family is Hmong, an ethnic minority group in Vietnam, China, Thailand, and Laos. During the U.S. military’s secret intervention in Laos, the Hmong people sided with the Americans. They were subsequently targeted by the Laotian government, and many were forced to flee into Thailand. Yang’s family left the mountains of Laos in the 1970s. When the Thai government started closing its refugee camps, many Hmong people were resettled, and Yang’s family landed in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Yang, who was born in a refugee camp in Thailand and resettled with her family at age six, became a cultural and linguistic bridge for her parents as they navigated life in America. Her first memoir, The Latehomecomer, which won the 2009 Minnesota Book Award, centers on her grandmother’s stories, which shaped Yang’s childhood. The Song Poet, winner of the 2017 Minnesota Book Award, is a tribute to her father, Bee Yang, whose “poetry shields us from the poverty of our lives.”

The book covers a wide swath of Bee’s life, from his birth in a hut in the mountains of Laos to his struggles parenting a teenage son who encounters racism in suburban Minnesota. As a fatherless boy in a Hmong village, Bee gathers the words of his neighbors and recites strands of oral narrative from memory. Through song and poetry he learns to share “stories of hurt and sorrow, of missing and despair, of anger and betrayal.” But he loses his ability to sing poetry after his mother dies in America many years later, his heart broken with her loss.

Structured as an album with Side A (in Bee’s voice) and Side B (in Yang’s voice), the memoir easily moves between perspectives and across time. In the introductory “Album Notes,” Yang reflects on her father’s performance one year at the Hmong American New Year celebration in St. Paul. Her account tells a universal story: a child’s blind adoration falls away to recognition of her parents as people with complexities and flaws. In telling human stories with nuance and detail, Yang deftly extends the genre beyond the “noble refugee” trope: it paints a relatable portrait that doesn’t allow the reader to write off the experience as too “other.”

Yang tells her father’s story with the same kind of lyricism that he demonstrated in his song poetry. “Love Song”—which covers her parents’ relationship, from their introduction in the jungle as they fled the Laotian soldiers to their years of working menial jobs in America—is structured like a song. “I loved you when. . . .” each paragraph begins.

I loved you late at night when the sound of the crickets grew fierce and unafraid, and we could hear the scurrying of mice along the floor, but your head was on my shoulder, your hand was on my heart, and the smell of your green Parrot soap wafted up to my nose and invited me to play in a garden of fresh flowers lush with rain, to swim in streams warmed by the day’s hot sun.

In “Cry of Machines,” Bee wrestles with the moral sacrifices he has made to ensure his children’s survival: first, as a drug runner for Thai soldiers in the refugee camp, and later as a machinist enduring verbal abuse and inhaling hard metal particle dust in a Minnesota factory.

Like many newcomers to America, Bee channels his struggles into hope for a better life for his children. Yang and her siblings feel the weight of their parents’ expectations: “Doctors and Lawyers” reveals the family strain that occurs when children outpace their parents’ education.

“Return to Laos (Duet)” describes how Bee travels back to Laos to see the land he’d left decades earlier, only to be denied entry. He is so close to return: he literally stands on the earth in Laos. But the border officer remarks: “We forced you out of our country once, do you want us to do it again?”

Yang’s stories stretch us past our instincts to shield ourselves from the pain of others. We cry as Bee’s two-year-old cousin is shot while tied to his father’s back as he runs through the jungle, and we witness Bee’s uncle being captured and tortured when he refuses to abandon his dying son. We experience Bee’s guilt as he leaves his uncle behind to cross the Mekong river into safety. We gasp when we read Yang’s description of her great-uncle’s mental deterioration: “What happened in Laos has happened inside of him. Like the country, he is now a collection of open pits, broken trees, and burnt houses.”

It’s in such vulnerability that we receive Yang’s greatest gifts to her readers: a window into an otherwise unfathomable refugee story, a daughter speaking her father’s voice in a language he will never master, a poetry that would otherwise be lost completely.