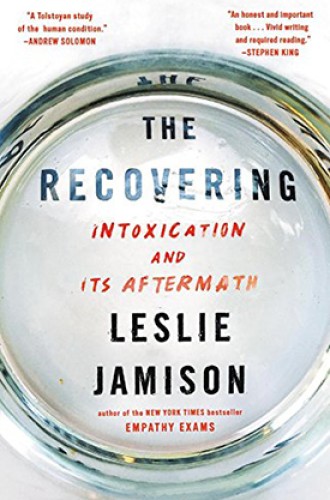

A personal narrative of addiction and the culture that birthed it

Leslie Jamison weaves cultural critique into her memoir about alcohol and creativity.

On the surface, Leslie Jamison’s book might appear to be just another memoir about addiction and recovery. Indeed, the author herself worries that what she has to say about her struggles with alcoholism will be dismissed out of hand: “Who would care? This is boring! When I told people I was writing a book about addiction and recovery, I often saw their eyes glaze. Oh, that book, they seemed to say, I’ve already read that book.”

As memoirist, Jamison starts at the very beginning: “The first time I ever felt the buzz I was almost thirteen. I didn’t vomit or black out or even embarrass myself. I just loved it.” (The intensity of this first taste for some is not unusual. Alcoholics Anonymous founder Bill Wilson experienced the same immediate euphoria.)

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

We learn about the divorce of Jamison’s parents when she was six, her longing for approval from a too-distant father, acute shyness, and anorexia and other forms of self-harm. Upon graduating from Harvard at age 21, Jamison gained a coveted spot in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. But all was not well. She found herself sleeping with near strangers, and blackouts became increasingly common.

The Recovering would be a worthy contribution to the genre of addiction memoirs if only because of the grace, beauty, and nuance of the writing. But it’s much more than memoir. It is also an extended essay—a treatise, really—on addiction, its causes, and our nation’s response over the past hundred years. Jamison not only takes us through the Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous as she followed them but also describes the origins and history of AA.

Significantly, she tells us that AA is not, for many, the only or even the best path to recovery: “Abstinence is a limited definition of healing that threatens to ignore the necessary work of harm reduction: clean-needle programs, supervised injection sites, over-the-counter distribution of [the life-saving overdose medication] Narcan, and medical care for addicts.” Her eloquent endorsement of harm reduction, at a time of serious debate on the topic, is a major contribution.

Jamison inserts historical accounts of how the federal government came to demonize drug users. The fanatical bureaucrat Harry Anslinger, starting in the 1930s, became the drug enforcement world’s version of J. Edgar Hoover—a bully, casting all drug users as criminals, to be treated as lepers. She then takes us through Richard Nixon’s racist motives for declaring a war on drugs and recounts how Ronald Reagan turned the concept into a vast, quasi-legal, quasi-military operation that fights mindlessly on despite overwhelming evidence of failure.

Jamison helps us think about addiction as a disease rather than a moral failure. She also raises the sociocultural dimensions of how society views addiction, respectfully acknowledging the insight of Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow, that it is primarily people of color whom we jail for drug offenses. She cites the poignant example of Billie Holiday, traumatized by sexual abuse at age six and a drug user before her teens, hounded as a criminal until she died at age 44 while chained to a prison hospital bed.

Jamison’s personal story is a constant thread. We see her, often alone, binge eating and watching old TV movies. Remarkably, we learn that she has been admitted into the PhD program in English at Yale. She gives new meaning to the term “functioning alcoholic.”

Her thesis explores drinking, sobriety, and creativity as viewed through the struggles of poets and novelists. In The Recovering, we learn much about John Berryman, Raymond Carver, Charles Jackson, Denis Johnson, Jean Rhys, David Foster Wallace, and others. The topic is a personal quest: “examining authors who’d tried to get sober . . . trying to find a map for what my own sober creativity might look like.” She wants an alternative to Jack London’s “myth of the drunk prophet and his truth serum of booze.”

Wallace serves as a helpful guide for Jamison. In reading his novel Infinite Jest, she found herself “glad to know that it was possible for a book to make me thrill toward wellness.” She quotes Wallace’s belief that great art comes from “having the discipline to talk out of the part of yourself that can love instead of the part that wants to be loved.”

Jamison closes the book by describing her pilgrimage to the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State, overlooking the Pacific Ocean, to visit the gravesite of the poet Raymond Carver, who found a second life of creativity after addiction. Carver, she writes, “looked back on the drama of his first life and understood that his writing had happened despite this chaos, rather than fueled by it.” The poetry he wrote following sobriety “is electrified by gratitude and open-ended beholding . . . loving rivers back to their source was a way of surrendering himself to something larger than he could properly understand—the palpable splendor and awe of the world itself.” Preachers take note.

The final chapter is titled “Homecoming.” Jamison has not had a drink since 2010. She has satisfied herself that sobriety can be a platform, not a barrier to creativity. She casts all this against a background of how the US has struggled, so far unsuccessfully, to come to terms with drug use. If addiction is a cruel form of idolatry and spiritual death, Jamison implicitly calls us to bear witness to the sparkling beauty and creative center of life itself. The Recovering is a towering achievement on many levels.