Paradox at the heart of poetry

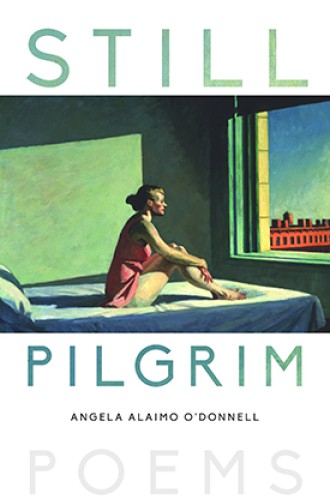

The Still Pilgrim—seemingly Angela Alaimo O'Donnell's alter ego—reflects joy and longing.

The poems in Angela Alaimo O’Donnell’s new collection embody an old and much neglected poetic virtue: they are companionable. They spring from a faith, which has been lost by many contemporary poets, in the human capacity to discern meaning in the shifting realities of our lives and to express that meaning (at least in a limited way) in language.

O’Donnell’s faith in poetry seems to be grounded in a deep Christian faith. She teaches English at Fordham and has published (among other prose works) a biography of Flannery O’Connor. This collection is O’Donnell’s seventh, and her poems—which have appeared with some regularity in the pages of the Century—locate themselves within the tradition of other Christian poets (think Gerard Manley Hopkins and T. S. Eliot, to mention two iconic examples) who accept the truth of the incarnation and see the world in its light.

A lovely poem in the final section of the book captures an important aspect of the poet’s vision. In “The Still Pilgrim Celebrates Spring,” spring weather brings into focus the transience of the world’s beauty: “For now the heat is bearable. / For now the light is gold and fine.” Yes, for now. For now, the spring days are gorgeous, but of course they don’t last, as nothing beautiful can in the world we know. And yet the poem affirms a deeper truth, which the spring also teaches: “for nothing is so riven here / that love can’t straight and make it whole. / . . . All that leaves returns. It’s fact. / The light we thought we lost comes back.” Without dogmatic assertion, this poem finds in spring a hint of final redemption—in Christian terms, a hint of God’s promised new creation.