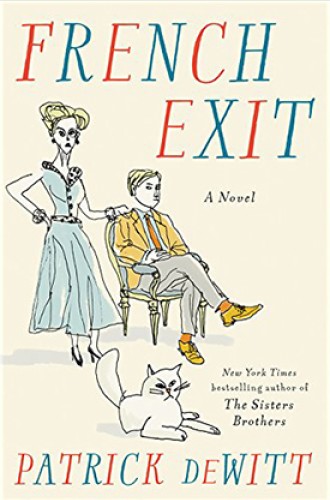

This novel about ridiculously rich people offers no simple lessons

Patrick deWitt is far too smart a writer to offer a sentimental narrative of redemption.

Frances Price is a ridiculously rich widow, so bored with life on Manhattan’s elite East Side that she creates her own financial crash by spending everything she has. When her financial adviser finally tells her that her worldly goods and homes are being repossessed, she seems relieved to withdraw all the cash she has left, which amounts to hundreds of thousands of dollars. That’s a massive amount to most readers, but it’s small change to Frances, the unforgettable antiheroine of French Exit.

The novel’s action begins when Frances takes off to Paris for a last hurrah with her son, Malcolm, a man-child whose only purpose in life is to follow his domineering mother around. He is as clueless as his mother when it comes to money and the role it plays in the average person’s life. Together, they begin their new austere lifestyle by taking a luxury cruise ship to Paris, where a wealthy friend from New York loans them her chic apartment. This is their version of slumming it.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The genius of Patrick deWitt’s storytelling is that these unsympathetic one-percenters, self-centered haves in a world of have-nots, soon become more real, and their fates become interesting. Money has not bought them love, friends, or community. Will they find it now, without their money? And yet, can people like the Prices ever really end up penniless? They have spent their lives running marathons in wealthy circles. (The mere fact that they think they will save money by living in Paris says it all.)

A hilarious trip on a cruise ship gets them to their destination. Readers listen in on Frances’s interior critique of all things plebeian, none of which prevent her from flirting and drinking with the ship’s captain. He’s so taken with the frosty socialite that he has his second-in-command leave the dinner table to look up the big words Frances uses and sneak back their definitions on tiny pieces of paper, so that he can appear to keep up with her wit.

The captain is the stand-in for us as readers, increasingly fascinated, confused, and attracted to this woman who is so used to power, wealth, and loneliness that she will say anything and offend anyone. Like American culture, which seems obsessed with the lifestyles of the rich and famous, the captain delights in any brush with Frances he can get, from the humorous insults that go over his head to a drunken sex romp that leaves both of them stunned to wake up in such odd company. And they haven’t even made it to Paris yet.

For a moment, I wondered if this novel would be an extended case study on the inefficacy of storing up treasures in barns. Meet Frances and Malcolm, both miserable, whose only shot at something more may be to give it all up. They do represent an extreme version of a luxurious life without religious community or reflection. They measure themselves against no tradition older than they are.

Frances, in particular, seems untroubled by her own behavior. When her husband died years ago, she left his body to rot for a few days so that she could go skiing—and has been remembered ever since for that one cold act, preserved forever in social media. As the novel goes on, we realize she had her reasons for leaving him, but her history of hurt and its resulting cynicism are not enough to make a meaningful life. This is the end of the road for someone who’s lived without the benefit of a weekly prayer of confession. As Frances ages, she is profoundly unhopeful, unable to imagine a new life for herself. She has no comfort in a life well-lived or even a place to put her suffering, which turns out to be real.

Will the few ragtag ordinary people that Frances and Malcolm meet in Paris turn things around? If this were a typical feel-good novel, they would, with each quirky character delivering a section of a shallow secular sermon in which all we need to know about life is already right in front of us. In the frothy philosophy of so much American fiction that passes for inspirational, there is never any need for religion, rigor, or rules. Wisdom comes to the lonely rich person in the form of a happy poor person who loves them into a life that seems more generous.

DeWitt is a far better storyteller than that. This is not a sentimental tale of redemption in which rich people voluntarily become poor, then decide that poor people have it better after all, then end up writing an uplifting book about it. DeWitt makes it clear that this story will end as it begins. Frances is going to stay mean and hard. Malcolm may stay winsome and weak, passively passing up the love of an intelligent woman he does not deserve, in favor of the cynical company of a mother only a coddled codependent son could love. There will be no chicken soup for the soul on the menu this week.

In the end, Frances’s existential options are limited. She must decide whether to make an exit, which has become the only way to make room in her son’s still soft heart for something or someone more. Without ever once mentioning church or God, French Exit could be read as a cautionary parable about a life without both. The fact that it is also hilarious is a testament to deWitt’s twin gifts as storyteller and satirist.