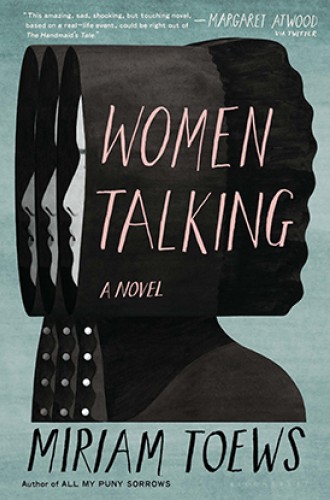

Miriam Toews imagines her way into an insular community grappling with sexual assault

In her new novel, women in a Mennonite colony plot their own liberation.

Early in Miriam Toews’s Women Talking, a woman speaks about her horses, which are named Ruth and Cheryl. When Ruth and Cheryl are attacked by a neighbor’s dogs, their owner reports, their “instinct is to bolt.” The horses do not “organize meetings to determine their next course of action,” she says pointedly to women who have organized meetings to determine their next course of action. “They run.”

Women Talking is a brutal phantasmagoria in which horses have women’s names and women are treated like horses. Mining sexual violence, patriarchy, religion, and the meaning of forgiveness and pacifism, the book is feminist dystopian fiction in the tradition of The Handmaid’s Tale, Vox, and The Water Cure. But where the what-ifs that populate those books’ imagined landscapes—What if fertility were your only currency? What if you could not leave your island? What if you were allowed only 100 words per day?—are speculative, Women Talking is built on actual events. Knowing that the novelist didn’t have to conjure an entire world but merely color in an existing one lends it an unnerving quality. This may be fiction, but that doesn’t mean it’s not based in fact.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Toews’s novel takes its cues from bizarre events that unfolded in a Mennonite colony in Bolivia, called Manitoba Colony. In the lowlands of that country, Old Colony Mennonites live in agricultural collectives, with an Amish-like rejection of electricity and cars but more self-governance and with little interaction with their Bolivian neighbors except in business transactions. Having been promised religious freedom, the right to run their own schools, and exemption from military service, the Mennonite colonizers were free to create their own ministates.

Between 2005 and 2009, women and girls in the Manitoba Colony were raped in the middle of the night. For years, they would awaken in the morning, groggy and aching and bleeding, with no clear memory of what had happened. For years rumors had abounded, with colony leaders blaming the nighttime attacks on satanic forces, what they called “the wild female imagination,” or women’s attempts to cover up adultery—until finally, in June 2009, a woman found two men entering her house. Eventually they named other offenders, and the grotesque method of their crime was discovered: a tranquilizer spray used on farm animals, which knocked the women and their families unconscious during the attacks.

An estimated 130 women and girls, ages three through 65, had been raped, many multiple times. Seven men from the colony were sentenced to 25 years in prison. When asked by a visitor whether the survivors of the abuse had access to therapy, the Mennonite bishop replied, “Why would they need counseling if they weren’t even awake when it happened?”

The novel, set in the fictionalized Molotschna Colony, is “both a reaction through fiction to these real events, and an act of female imagination,” writes Toews in a note at the beginning. And an unparalleled act it is. Toews is an esteemed Canadian novelist, and Women Talking may be her magnum opus. Once again, as she has done before, Toews leads readers into the cramped, intimate spaces of a severe Mennonite community and women’s lived experiences there.

This time, however, her novel drops into church foyers and coffee shops crowded with conversations emboldened by the Me Too movement. “No other book I’ve read in the past year has spoken so lucidly about our current moment, and yet none has felt as timeless,” writes novelist Lauren Groff.

A lesser novelist would have launched the book by narrating what have been called the “ghost rapes.” But Toews sets the action after the attacks, in the claustrophobic span of two days, as eight women meet in a hayloft to discuss their options. Their men have gone off to the city, where the offenders are being held by authorities, with the hope of paying bail so that they can bring the accused rapists home to await trial. The women and their children are safe, for now, but only because the colony has been temporarily emptied of most of the men. The women have two days to land on a plan and execute it: stay and do nothing, stay and fight, or leave. Setting the novel in this liminal time of refuge means that each woman’s backstory unspools gradually: one woman’s sister killed herself, another woman’s toddler was raped. This slow unraveling of disclosures elongates the horror.

The women invite August Epp, the colony’s teacher and the novel’s narrator, to take minutes of their meetings. They will not be able to read them, however, as the hermetic seal of premodern religion has kept out the air of literacy and even a basic sense of geography. (“We don’t know where to go,” one woman says, as they contemplate the flight option. “We don’t even know where we are!” says another.) August, whose own tragic story is parceled out over the course of the novel, becomes the women’s mostly silent secretary, translating words from their language, Plautdietsch, into English and writing them down. Occasionally he interjects ideas, until the women remind him that he “should not feel obliged to offer inspirational counselling.”

August’s silent, adoring love for one of the women, Ona, is a tender counterpoint to the brutality visited upon all of them. Ona is damaged in numerous ways, yet incandescent and articulate. Extended portions of the women’s conversation center on the nature of forgiveness, injury, and what pacifism requires. Ona’s reflections on these topics are always astute. “If I can understand how these crimes may have occurred, I am able to forgive these men,” Ona says. “And I am almost able, certainly from a distance, to pity these men, and to love them.”

As the women make lists of pros and cons—for leaving, on the one hand, and for staying and fighting, on the other—one young woman suggests that a rationale for the “stay” column is that they wouldn’t have to leave the people they love. Ona gently reminds her that “several of the people we love are people we also fear.”

Full of such agonizing lines, Women Talking blooms into a feminist fantasia, in which women plot liberation from both the men who violated them and those who defend them. The eight Loewen and Friesen women who argue their way toward a plan are fiery, animated, and often hilarious, as well as fluent in the language of metaphor and emotion. Several swear, one smokes, and at times they sound more like Gloria Steinem than any Mennonite woman I’ve ever met, even the progressive sort. “We are women without a voice,” Ona says. “We are women out of time and place.” She later articulates her vision for the place they can create if they leave the colony: “Men and women will make all decisions for the colony collectively. Women will be allowed to think. . . . A new religion, extrapolated from the old but focused on love, will be created by the women.”

Anyone who knows conservative Anabaptists of any stripe will probably find such dialogue implausible. Profanity and allegory are less likely to crop up than deference and apology, even when the menfolk aren’t around. Other pieces don’t quite fit either. One reviewer in a Mennonite magazine in Canada, where the novel was released last year, calls Women Talking “an amalgamation of the [town of the author’s] youth, Mexican colonies where she has spent time (quite different from Bolivian colonies), key bits of Bolivia, Hutterites perhaps (shared dining rooms) and her imagination.”

Yet who can blame a novelist for amalgamation and imagination? Maybe we should applaud Toews instead, for granting fictional women the scrappy speech and quarrelsome agency likely inaccessible to actual colony women. Each time I raised my eyebrows at some fabulous show of ambition or free thinking among the fictional Loewens and Friesens, I would think of photographs of Old Colony women, chins tipped to the ground and eyes hidden under hat brims. And I would long for some conduit from the fictional world to theirs, a channel of options flowing from Toews’s wild female imagination to their own.

Canadian historian Royden Loewen has suggested that Old Colony and Old Order Mennonites should be commended for their rejection of “the immense assimilative power of the globalized modern world.” But others have frequently found colony Mennonites in need of salvation, defined in a variety of ways. Evangelicals have launched soul-saving and Bible-reading efforts among them, and Mennonites in the North have questioned their commitment to education and Anabaptism. Journalists have criticized their primitivism, psychologists the authoritarian culture that allows domestic violence to go unchecked. Readers of Women Talking should be aware of this tendency toward the pejorative.

Toews’s novel ends with a slightly higher ratio of hope to despair than most of her previous works. “Perhaps it is the first time the women of Molotschna have interpreted the word of God for themselves,” August notes, as they consider what God thinks of their emerging plan. I’ll avoid spoilers by saying simply that the women decide to take action, decisively and together. Ruth and Cheryl are involved.

Perhaps Toews afforded her characters an arc of redemption in order to battle back the dystopian power of actual colony life, which showed an eerie penchant for iteration years after the time frame of the novel. In 2013, after the attackers were convicted and jailed, disturbing reports began to trickle out of the Manitoba Colony once again. Women and girls were once again waking up in the morning groggy, aching, and bleeding.

Read Elizabeth Palmer's interview with Miriam Toews.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Imagining liberation.”