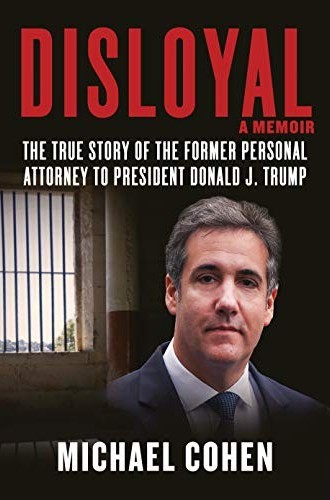

Michael Cohen’s tell-all about Trump is mostly about himself

The moral lessons of his humiliation and imprisonment seem fairly limited.

Reading Michael Cohen’s new book is like serving on jury duty. You don’t really want to do it, so you keep reminding yourself that you’re fulfilling a civic obligation. As you wade through the intricate facts of the case, struggling to decide which version of events to believe, you keep thinking about how much you dislike the lawyer. You wonder if you can trust anything he says. Then he turns to the jury box, looks you in the eye, and says:

You will no doubt ask yourself if you like me, or if you would act if I did, and the answer will frequently be no to both of those questions. But permit me to make a point: If you only read stories written by people you like, you will never be able to understand Donald Trump or the current state of the American soul.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

That’s a good point, you tell yourself, and then you tune in for more details about outrageously selfish people doing unconscionable things to gain power and wealth.

Like the two subtitles that compete for space on its cover suggest, Disloyal is a cross between memoir and political tell-all. It’s a fascinating character study that’s never quite clear on who the main character is: Cohen or Trump. At times, they seem to be the same person. “That’s how connected we were—like Siamese twins,” Cohen comments after explaining that the contact lists on their phones were synced. “If one of us called the other, we answered immediately, like the inhalation and exhalation of breathing together, or conspiring. . . . Partners in crime.”

Cohen’s portrayal of his time working for Trump seriously challenges the Christian belief that even the worst people have some goodness in them. Still, readers looking for bombshell revelations about Trump will be disappointed. Most of the data is about Cohen himself, who describes in great detail how he was spurred on to swindle, threaten, lie, and do anything else necessary to make Trump money (and later to make him the president). Cohen is clear on what motivated him: a toxic mix of his desire for approval, his addiction to power, and Trump’s orders (both implicit and explicit).

The book succeeds in helping readers imagine what it must be like to live inside Trump’s mind (or to work with him on a daily basis). A slow and steady buildup of anecdotes supports Cohen’s characterization of Trump as “a cheat, a liar, a fraud, a bully, a racist, a predator, a con man.” Some of the book’s content is new—the Obama lookalike whom Trump hires so he can belittle and fire him on video; the scornful, “Can you believe people believe that bullshit?” after a group of evangelicals pray over Trump; the $15,000 purchase of 200,000 IP addresses to fix an online poll; the lurid details of the strip club show Trump watches with a Russian oligarch in Vegas. Much of the book is disgusting. But none of it is surprising in light of what Trump has already shown about his character.

The most fascinating character in the book is Cohen himself. He begins with the premise that nearly everyone considers him a “liar, snitch, idiot, bully, sycophant, convicted criminal, the least reliable narrator on the planet,” and he takes responsibility for the “terrible, heartless, stupid, cruel, dishonest, destructive choices” he made. He names his character flaws: “my own considerable ego, short temper, and willingness to deceive to get ahead, regardless of the consequences.” In some ways, the book feels like a confession or conversion narrative.

Cohen uses a variety of metaphors to explain his descent into the illusory world where helping Trump cheat, lie, steal, and become president seemed like a good idea. He likens himself to a “demented follower” caught “under the spell of a cult leader,” a “junky in need of a fix,” a person with mental illness who had “departed from reality,” a method actor playing a character “for the press, repeating lines from the script,” someone who’d sold his soul in a Faustian bargain, a prisoner with Stockholm syndrome. Still, at several points he accepts full responsibility for his actions, identifying a distorted sense of loyalty as his fatal flaw but also naming his other faults (like taking pleasure in the power to hurt people).

Given all of this, an obvious question arises: Is Cohen a trustworthy narrator? He supports some of his stories with photos, screenshots, and documents, but he also gives the impression that there’s a lot that he’s holding back. Plausible deniability rings as a refrain throughout the book, and it’s hard not to wonder if the wool Cohen pulled over so many other people’s eyes is now being used on readers.

What’s most convincing about Cohen’s portrayal of himself is that the moral lessons he learns from his public humiliation and imprisonment are fairly limited. He believes he’s learned a lot from his experiences and emerged as a better person. That may be true, although it would be pretty hard not to be a better person than the Michael Cohen the book describes. Still, he seems genuinely sorry for his unethical actions. But traces of misogyny, outsized pride, and contempt for anyone who’s weak or poor—the same attitudes that made him a natural fit for the Trump Organization—continually peek through the narrative.

Cohen may have had time to reflect on his errors when he was in jail, but he’s still a multimillionaire whose fortune was built on the backs of New York City taxi drivers who suffered as he profited off of the inflated value of medallions. He’s now dining at expensive restaurants after being released from jail early due to the pandemic, while many of the vendors he cheated out of their payments have now lost their businesses to COVID-19.

In the end, though, Cohen’s trustworthiness may not be the most important thing. If we only read stories by people we trust, we may never be able to understand Donald Trump or the current state of the American soul. And if even 1 percent of the content of Disloyal is true, its thesis—that Trump’s presidency is a danger to democracy—is well supported.