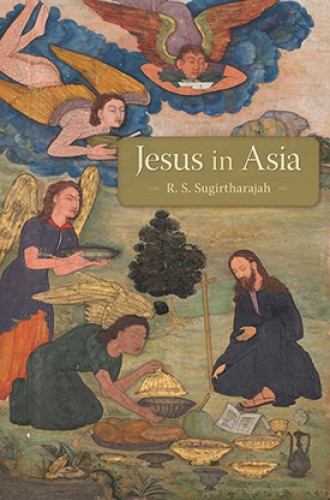

The many Jesuses of Asia

From Hindu Bible commentary to Christian minjung theology, the Asian Jesus has taken many forms.

The topic of this excellent book—Asian quests to interpret the Jesus of scripture, history, and faith—will be new to most Western Christians. R. S. Sugirtharajah brings together some fascinating parts of the global and perpetually expanding biography of Jesus. This particular expansion is a manifestation of the creative, idiosyncratic personalities of those who read scripture in Asian contexts. It also reflects the desire of Christians to present Jesus in a culturally appealing garb.

Sugirtharajah begins with some of the earliest Asian biographies of Jesus. The Nestorian Monument is a stele etched in the seventh century by Church of the East missionaries in Tang China, and the eight scrolls known as the Jesus Sutras were produced in approximately the same time and place. In these depictions, attentive as they are to Buddhist and Taoist ideals, Jesus preaches mindfulness along with the doctrines of “no desire,” “no piousness,” “no doing,” and “no truth.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Mirror of Holiness, produced a millennium later by the Jesuit Jerome Xavier (nephew of the famous Francis Xavier) in the north Indian Mughal Muslim court of Emperor Akbar, portrays Jesus in ways intended to appeal to Mughal rulers while at the same time asserting the truth of Christian (as opposed to Muslim) understandings of Jesus. Xavier downplays Jesus’ ethical prescriptions which might have offended the royals (such as those on marriage and divorce) while portraying Jesus as a perfect soul, miracle worker, and crucified Messiah. The latter point refutes Muslim assertions that Jesus was not crucified.

The bulk of Sugirtharajah’s story concerns more recent centuries. For Hong Xiuquan, leader of the momentous 19th-century Taiping Rebellion in China, Jesus was not God, but merely the firstborn of many potential sons of God who were inferior to their father but superior to the angels. Drawing upon Confucian, indigenous Chinese, and Christian traditions, Hong referred to Jesus as his “Heavenly Elder brother,” which conveniently but controversially implied Hong’s kinship with Christ.

The late 19th- and early 20th-century Sri Lankan Ponnambalam Ramanathan, a Hindu, is thought to have produced the earliest Asian biblical commentaries. In Ramanathan’s appreciative portrayal (and in keeping with the author’s Saiva Siddhanta Hinduism), Jesus becomes a “Judean Jnana Guru” who “found Christ within himself, and . . . attained God,” a pure, fully realized, and awakened spirit operating within the impure fleshy confines of a body which was “no better than a carcass.”

Sri Lanka was also the home of Francis Kingsbury (C. T. Alahasundram, 1873–1941), who was influenced by Saiva Siddhanta traditions but converted to Christianity. Kingsbury was a skeptic, and his biographies of Jesus omit elements of the Gospel accounts that he considered historically implausible. The result, according to Sugirtharajah, “is not the divine human being of traditional orthodoxy, but simply a human being like any other,” or to put it another way, “Jesus without a Halo.”

In India in the early 20th century, Thakur Kahan Chandra Varma and Dhirendranath Chowdhuri drew upon the Western Jesus myth movement to assert that there was no “historical Jesus.” Instead, they asserted, early Christians conjured Jesus by amalgamating episodes from the existing religious stories of those who lived around them.

The book includes numerous South Asian depictions of Jesus that draw upon or attempt to appeal to Hindu sensibilities. Those that emerge from a Jain frame of reference are rarer, but Sugirtharajah tells the story of Manilal Parekh (1885–1967), who was a Jain convert to Christianity. Parekh insisted that becoming Christian did not require him to renounce his Jainism, and he was skeptical of the historical value of the Gospels. Instead of emphasizing the ethical teachings of Jesus, Parekh focused on Jesus the yogi’s abstinence, long prayers, and fasting—his “self-surrendering devotion.” Here Jesus resembles the Jain tirthankaras, those fully realized souls who have conquered all human passions.

In this same time period, the Minjung theology of South Korean Ahn Byung Mu (1922–1996) arose. Ahn’s Jesus, developed in the face of an oppressive regime, was a Galilean villager who understood the struggle of the “culturally exploited, politically victimized, and economically weak masses [the minjung].” For Ahn, the life of Jesus was not a “once-and-for-all event that happened way back in Jerusalem” but a “continuous happening,” like the ceaseless flow of a volcanic eruption. As Sugirtharajah puts it, “Minjung events in Korean history are Christ events and Christ is active in all minjung events. The uprisings of the minjung, then, are seen as a kind of Christ event.”

Sugirtharajah ends by discussing Shūsaku Endō (1923–1996), who is better known in the West as a novelist than as a biographer of Jesus. In A Life of Jesus Endō presents an intriguing reconstruction of Jesus. Distinguishing biblical “truths” from “facts” (and distrusting the way the Gospels present many of the latter), Endō depicts Jesus as a weak and ineffectual but co-suffering “‘Japanese’ person whose humanity, compassion, and spirit of self-sacrifice were more pronounced than his Davidic descent or his relationship with a mysterious ‘Father in Heaven.’”

According to Sugirtharajah, all of these portrayals of Jesus are—among other things—acts of decolonization wherein Asian writers “unearthed and rediscovered Asia’s spiritual treasures as an anti-colonial strategy, . . . a notable early attempt at ‘provincializing Europe.’” Many of these depictions will seem strange or inaccurate to Western Christians, but Western Christianity has tended to obscure or deny the parochial nature of its own interpretations of Christ. “The so-called historical Jesus,” Sugirtharajah writes, “is invariably an idealized picture drawn from the interpreter’s fancy and from fads.”

Jesus in Asia does not attempt to present a nonsectarian history or chronicle of diverse Asian portrayals of Jesus. It is, above all, a work in biblical hermeneutics. Sugirtharajah regularly compares the Asian depictions of Jesus to those of “orthodox” Christianity or the “Jesus of the Gospel.” He occasionally includes his subjective appraisal of these depictions, as when he faults the Mirror of Holiness for “lamentably” lacking the “essential characteristics of Eastern mysticism.” When Sugirtharajah writes of the “scholars” who have thought about Jesus, he means Christian scholars. Christians, too, are the audience for this book. Within that realm, Jesus in Asia deserves to be read widely.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Judean guru.”