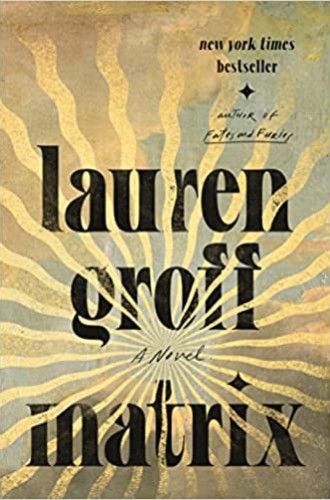

Lauren Groff builds a proto-feminist medieval world

But the enchantment of Matrix is ultimately broken by her language.

When I read the opening lines of Lauren Groff’s Matrix, the challenge the book presented was clear. To make this part-historical, mostly imagined world convincing, the novel was going to have to absorb me in its language. I couldn’t be thinking all the time, “How realistic is this? Would some woman in medieval Europe really have thought/said/done this?” The stretch into the mind and heart of a medieval woman was dramatic enough that ordinary contemporary language would not do.

Groff largely succeeds. The language of the novel holds its own, with startling cadences and vocabulary that make it clear that you are in another world and you like being there. “The new prioress Tilde, twitchy and scrupulous, with the sweet, startled face of a dormouse” reads one phrase, delightful in its specificity and strangeness, with a slight Alice in Wonderland feeling. By several pages in, I had given up on realism and was along for the ride.

The ride is the story of a 12th-century abbess named Marie, an unacknowledged child of a king, or in the language of the novel, a “bastardess.” The story follows Marie from the failed Children’s Crusade to the court in France of her half-sister Queen Eleanor to her exile in an English abbey. It examines her rise to power, her ambition, and the relationship between her physical and spiritual hungers. The novel keeps a brisk pace through the abbess’s life, pausing for intimate and sensual details—a look inside the mind of the abbess or of those who admire or hate her—and then it takes off again, letting decades run through the reader’s fingers.