John Henry Newman’s impact

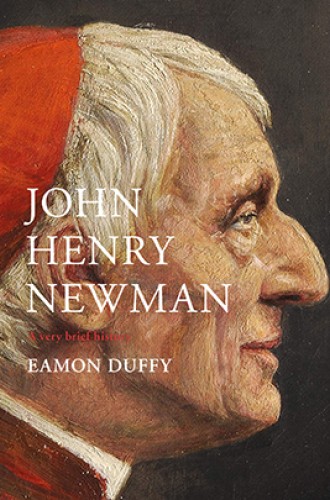

Eamon Duffy’s short biography of the first English saint canonized since the Reformation

“I have no tendency to be a saint—it is a sad thing to say, Saints are not literary men,” John Henry Newman wrote to a correspondent in 1850. But the Catholic Church has judged differently. Last October, Pope Francis conferred sainthood on the eminent cardinal and man of letters, completing the two-stage process that began with his beatification in September 2010. Newman is the first English saint to be canonized since the Reformation.

Irish historian Eamon Duffy provides a timely, balanced introduction to Newman’s life. This is no easy task in light of Newman’s many published works, diaries, and extant letters (20,000—among the most of any major Victorian figure) and given the intense passions Newman aroused both during his lifetime and afterward. Protestants did not trust him because he converted to Catholicism in 1845. Monsignor George Talbot, chamberlain to Pope Pius IX, once called Newman “the most dangerous man in England.” Talbot was worried that Newman, precisely as a convert, did not fully toe the line on papal authority and thus might lead well-meaning Catholics astray.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

During his lifetime, Newman was peripheral to many Catholic affairs, which had the European continent as their primary theater. But since his death in 1890, his stature has only grown. Some would rank him with Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, and a handful of other giants of Christian thought.

While Newman’s name was seldom invoked during the Second Vatican Council (1962–65), Duffy makes it clear that some of its key concerns and outcomes derive ultimately from his example. This is especially true with respect to granting the laity greater say in church practice and teaching—something taken from Newman’s notion of sensus fidelium, the living sense of the faith held by practicing believers. It is also true with respect to Newman’s idea of “the development of doctrine,” his view that church doctrine is not static but matures into greater fullness and understanding over time. Arguably, this idea permitted the church to modify its teaching on religious freedom in the 1965 conciliar document Dignitatis humanae, which makes the case for religious liberty on the basis of innate human dignity.

But Newman’s influence far transcends the Second Vatican Council. It extends especially to higher education. Tapped by Ireland’s bishops to found a Catholic university in Dublin in the 1850s, Newman used the occasion to offer a series of lectures on the rhyme and reason of serious learning. These lectures were later gathered into a book, The Idea of a University, which according to Duffy now stands as “the classic defense of liberal education.”

For readers in the current age of soaring costs, administrative bloat, and intense politics in higher education, this book sketches out a simpler and more profound view of education’s aims: “wisdom,” “the enlargement of mind,” “the formation of character,” and instruction in the ability “to grasp things as they are” and to develop “the instinctive just estimate of things.”

Duffy also emphasizes Newman’s pivotal role in moderating interpretations of papal infallibility—a teaching that made Newman cringe. In the view of many 19th-century papal loyalists, the teaching—defined for the first time at the First Vatican Council (1869–70)—meant that the pope’s every utterance was a veritable oracle of God. Protestants, led by the British prime minister William Gladstone, charged that this teaching suggested that Catholics henceforth would be a fifth column in any government, since their ultimate loyalties were to a “foreign despot” in Rome.

Newman would have none of it. He penned a nuanced interpretation of the teaching in his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, in which he famously called conscience, not the pope, “the aboriginal Vicar of Christ.” He pithily added: “Certainly, if I am obliged to bring religion into after dinner toasts . . . I shall drink,—to the Pope if you please, but still to Conscience first, and to the Pope afterwards.”

Duffy recognizes that Newman, like all saints, at times had clay feet. He could be domineering in relationships, easily offended, callous, and slow to forgive. Even so, Duffy concludes with praise:

Newman possessed one of the most original Christian minds of modern times, indeed of any time. His significance for the Catholic Church, and for all churches, is neither as a model of mere piety, nor as a paragon of conformist orthodoxy, but specifically as a teacher and exemplar of Christian thinking at the edge; for the patient, generous, attentive, and interrogative mind he brought to bear on questions of good and evil, meaning and purpose, that are at the heart of religion.

Plenty of longer scholarly studies on Newman have been written, and beyond them Newman’s own works and letters also beckon. For now, though, the most rewarding point of entry to the recently sainted cardinal’s luminous and capacious mind passes through Duffy’s concise, highly rewarding study.