Imagining our way out of systems of disgrace

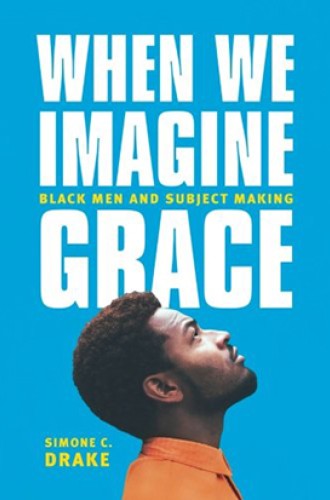

Simone Drake’s book helps readers grow in understanding of a deeply marginalized group: black men.

Reading is occasionally an illicit experience for me. Intrigued by a title, theme or popular response, I dive into a book. I read and absorb the material, but along the way, an awareness arises: I am not the intended audience. I am not the one for whom this book was written. Should I even spend my time reading it?

Simone C. Drake’s book had this effect on me. Drake, who teaches African-American and African studies at Ohio State University, desires to “empower black people.” I am a white woman. My marriage to a black man and the birth of our biracial sons do not (and will not ever) provide me with an innate understanding of what it means to be a person of color in America today. But these relationships have propelled me toward understanding what it means to grow up with skin different from my own. With discomfort, I’ve leaned into new viewpoints and sharpened my understanding of my misperceptions. And I’ve learned that I can no longer deny nor feign ignorance when it comes to issues of race.

In this sense, Drake’s book is not illicit. It’s crucial for readers of all races. It affirms that everyone must seek to grow in understanding in relation to members of the most marginalized of racial and ethnic groups: black men.