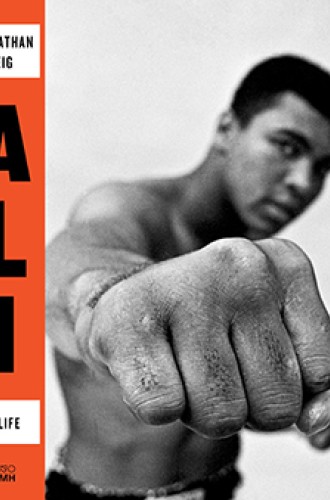

How Muhammad Ali influenced public debate

Jonathan Eig's biography shows how the boxer took on opponents in multiple arenas.

Muhammad Ali was hardly ever quiet or still. As a young man, he was handsome, brash, and charismatic. His loud southern voice sang out in rhymes, brags, and opinions, as if the world were his carnival show. A brilliant entertainer and athlete, Ali reached a level of media attention and cultural fame surpassed in his time only by Elvis and the Beatles.

Even after his boxing career was over—his brain addled by years of blows to the head, his hands trembling with Parkinson’s disease—Ali’s personality radiated a warmth that still attracted crowds. President Jimmy Carter named Ali a special emissary to Africa. George W. Bush presented him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, calling the boxer “a fierce fighter and a man of peace.”

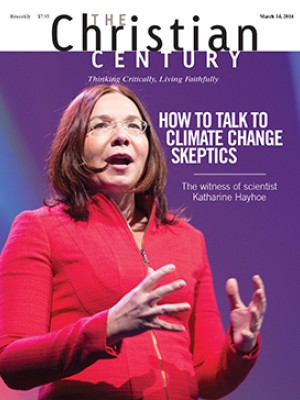

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

As a high school student in Louisville, clowning for his classmates and drawing attention to himself with boxing skills and abrasive humor, the young man, known then as Cassius Clay, desired the kind of happiness he felt when he was the center of attention and the kind of wealth he thought only some white people had. But he was a mediocre student, and his high school diploma was a “certificate of attendance” presented for academic efforts that placed him near the bottom of his graduating class.

Years later, rising toward the fame and fortune he wanted, he explained with characteristic innocence that as a young adult he believed that boxing would be the fastest way for him to achieve his goals. The provocative and constructive influence Ali had on debates about race relations, the morality of military service, and interfaith investigations resulted largely from his gift for showmanship and impulsive honesty.

In the 1960s Ali emerged from the shady underworld of prizefighting as a made-for-television athlete. A brazen self-promoter, he baited and bullied one opponent after another, drawing onlookers’ attention and pumping up interest in his next fight. Throughout his life he needed people to see him and watch him—even if they came to boo him, see him bleed, or be beaten unconscious.

Ali became convinced that the religion of Jesus had been pressed on black slaves by white slave owners, and he vowed allegiance to Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam, with its teachings of black power and black nationalism.

His rejection of Christianity was also a stamp of the young Ali’s independence and defiance. “I was baptized when I was twelve, but I didn’t know what I was doing,” he said. “I’m not a Christian anymore. I don’t have to be what you want me to be.” His choice of the militant Nation of Islam put Ali at odds with black leaders who advocated incremental, nonviolent steps toward racial equality and civil rights.

In 1966, Ali claimed conscientious objection to the draft. His lawyers argued that their client spent 90 percent of his time preaching and 10 percent boxing and therefore qualified as a Muslim minister and was entitled to an exemption. The Department of Justice appeals board rejected Ali’s claim, writing that his objection to the draft was based on political and racial convictions, not on pacifist religious opposition to all wars. In 1967, a member of the Houston draft board called Ali’s number. The fighter refused to step forward. A naval officer informed him that he was committing a felony, punishable by a $10,000 fine and five years in jail. Ali was stripped of his championship. Boxing commissions around the country revoked his license to fight.

After three years of appeals, Ali’s case was resolved by the U.S. Supreme Court. Ali was free to return to boxing. Some Americans admired Ali as a symbol of protest and resistance, while others despised him as an unpatriotic coward. One of his detractors lived in the White House. Richard Nixon had a special television line installed so that he could watch Joe Frazier’s 1971 fight against “the draft-dodging asshole Ali.”

The postscript of Eig’s carefully researched biography is an anecdote. In 1966, Martin Luther King Jr. was in Chicago, organizing grassroot actions against discriminatory housing practices. King rallied residents in the Garfield Park neighborhood to pool their rent payments into a fund that would be used to repair the buildings they lived in. Facing eviction for participating in this protest, one family watched sheriff deputies remove their belongings from their apartment and pile them beside the street.

A University of Chicago law student heard of the eviction. When she arrived at the site, a crowd had gathered. As she watched, she felt a hand on her shoulder and turned to see the famous boxer. Ali handed his seersucker jacket to the law student, stepped out from the crowd, and began moving the furniture back into the apartment. The sheriff’s deputies stood by. People from the crowd joined in. Then Ali, at the height of his strength, a few months before he would be banned from boxing, drove away without saying a word: the center of attention, never afraid of a fight, doing more good than harm.