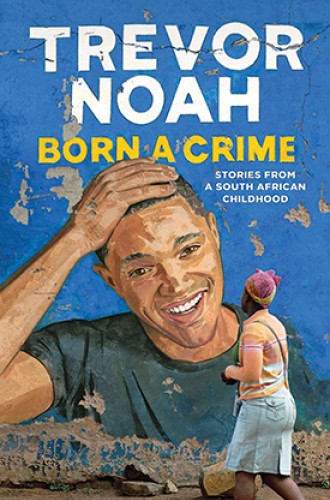

The hero of Trevor Noah’s story

If you think the Daily Show host is funny, you should meet his mother.

At least one good thing has come out of recent political events: a flood of films and books reflecting the experiences of people of color. When the presidential campaigns began, Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me topped the New York Times hardcover nonfiction best-seller list. Soon after the inauguration, Moonlight won the Oscar for best picture. Many other straight-talking books (like Just Mercy, The Underground Railroad, and Homegoing) and hard-hitting movies (Fences, The Birth of a Nation, and 13th) have also attracted large audiences. Most are deeply troubling. A few are inspirational. Trevor Noah’s memoir is both.

Published a week after the election, this collection of 18 stories provides a welcome break from the angst that has settled over much of America since then. Noah is not an American, but he knows race. Born in South Africa to a white Swiss-German father and a black Xhosa mother when his very existence broke the law against interracial coupling, he did not fit any of his country’s legally mandated racial categories. His black cousins considered him white. White kids thought he was colored. Colored kids spoke a different language. And he obviously wasn’t Indian. “I was the anomaly wherever we lived,” he writes. But he was philosophical about his outsider status. “I learned that even though I didn’t belong to one group, I could be a part of any group that was laughing.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Fortunately, Noah is good at making people laugh. Within a few years of finishing high school, he had become one of South Africa’s top comedians. By age 30 he was making regular appearances on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, which soon became The Daily Show with Trevor Noah. The boy who spent his earliest years in his grandmother’s two-room house in Soweto with “just one communal outdoor tap and one outdoor toilet shared by six or seven houses” has come a long way. According to the Wall Street Journal, Noah, now 33, recently bought a 3,600-square-foot, $10 million Manhattan apartment with three and a half baths.

He doesn’t mention his adult achievements in Born a Crime, however. His humor is mostly self-deprecating—“I was the acne-ridden clown with duck feet in floppy shoes,” he writes—and his stories end before his career begins. Rather than a rags-to-riches success story, the book is a memoir about survival against the heavy odds of racism, poverty, hunger, and abuse.

How did he survive? And why is the book so cheerful? In a word, Mom. “I thought that I was the hero of my story,” Noah told NPR’s Terry Gross, but “in writing it I came to realize over time that my mom was the hero. I was lucky enough to be in the shadow of a giant.”

Mom, aka Patricia Nombuyiselo Noah, was partly raised by an aunt along with 14 cousins who were unwanted by their parents. By the age of six or seven, she was collecting deposits on empty liquor bottles so she could buy food for neighborhood toddlers who were worse off than she was. After learning English at a mission school, she took a secretarial course and then moved to a whites-only section of Johannesburg, where prostitutes taught her how to avoid police detection. She chose her best friend, a white man, to be Trevor’s father, knowing full well that she could be imprisoned for giving birth to a light-skinned child.

Noah’s stories about his mother are often funny but never sentimental. “I was nine years old when my mother threw me out of a moving car,” one begins. When Trevor, age ten, stole a pack of batteries, Mom said to the security guard, “Take him to jail!” (The guard, dumbfounded, didn’t.) “If I don’t punish you, the world will punish you even worse,” she told her son. “The police don’t love you. When I beat you, I’m trying to save you. When they beat you, they’re trying to kill you.”

At times Patricia economized on petrol by making an embarrassed Trevor push their old car up hills and saved money on food by serving the family wild spinach and caterpillars. At the same time, she readily bought books to share with him. “She taught me to challenge authority and question the system,” he writes. “The only way it backfired on her was that I constantly challenged and questioned her.” I laughed out loud at Noah’s descriptions of his mother’s “faith-based obstinacy,” forcing him to attend religious meetings most weeknights and three times on Sunday. It wasn’t all bad. “Christian karaoke, badass action stories, and violent faith healers—man, I loved church,” he admits.

But wait—how can we laugh at stories whose setting is apartheid and the tumultuous years following its demise, a time when “very little white blood was spilled [but] black blood ran in the streets”? Steve Allen, host of The Tonight Show in the 1950s, once wrote that “tragedy plus time equals comedy.” Noah is funny because, from the distance of a couple of decades, he can see humanity in all its quirky glory, even in the midst of dire oppression.

Still, one of Noah’s stories is dead serious. When he was in elementary school, his mother married a charming auto mechanic. Abel, it turned out, was mean when drunk, and he was drunk much of the time. He viciously beat up a neighbor kid. He struck Trevor. He drank up Patricia’s savings and periodically battered her. She complained to the police, but the police refused to file reports. Eventually Abel tried to kill her.

Noah could find no humor in this event—but his indomitable mother could. When she awoke in intensive care, Trevor, sitting by her hospital bed, was weeping uncontrollably. “My child,” she said, “you must look on the bright side.” “What?” Trevor exclaimed. “Mom, you were shot in the face. There is no bright side.” “Of course there is,” she responded. “Now you’re officially the best-looking person in the family.”