The fundamentalists, the modernists, and the oil they both swam in

Darren Dochuk shows how oil and American Christianity have long shaped each other.

Oil is all around us. It’s in our cars, our planes, and our plastics. News of its latest spills splashes across our social media feeds. Its profitability tempts our politicians and funds our philanthropies and schools. Oil bubbles just beneath the surface of numerous contemporary political debates. Still, it is easy to forget oil’s ubiquity because energy regimes are structured in ways that make forgetting possible. Thankfully, recent scholars have been shining light on the sometimes invisible oil industry and how it has affected society.

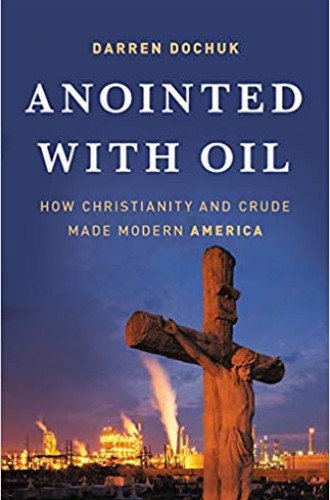

Historian Darren Dochuk makes an important addition to this growing literature. Whereas most scholarly works and popular media depict oil and religion as either separate or in tension, Dochuk, who teaches history at the University of Notre Dame, suggests that the oil industry has shaped—and been shaped by—religion.

At the outset of the book, Dochuk describes the “two sparring spirits of capitalism” that animate his story. He refers to these spirits as the “civil religion of crude” and “wildcat Christianity.”