The formation of Martin Luther King Jr.

Motivated in part by the whitewashing of a radical legacy, Patrick Parr explores King's seminary years and the roots planted there.

Martin Luther King Jr. is one of the best known and least understood Americans of the 20th century. Fifty years after his assassination, the contrast between his life and memory could hardly be more stark. In the eyes of countless white Americans, King died a communist villain. He has been resurrected as a loveable mascot for an ever-improving American way.

On the January holiday that commemorates his life and legacy, we hear little about King’s strident opposition to racial and economic inequality at home, not to mention his vociferous denunciation of American imperialism abroad. Instead attention is directed to selective snippets from his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech and especially this line: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” Ripped out of context, this one sentence might seem to suggest that King was a cheerleader for colorblind liberalism, seeking only formal, not actual, equality.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

But King was far more radical than that. He had democratic socialist sympathies and fought doggedly for a more egalitarian distribution of wealth. The fact that his ties to the progressive labor movement have been scrubbed from the typical story is all the more amazing given that the reason he was in Memphis when gunned down there in April 1968 was to stand with striking sanitation workers.

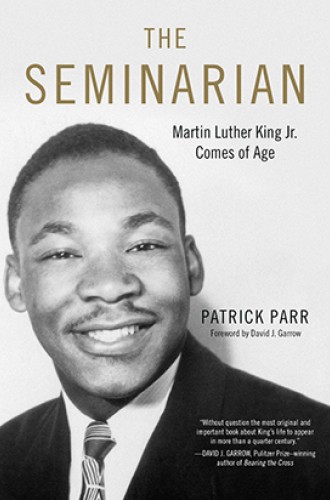

Concern about such whitewashing is part of what motivated Patrick Parr to write The Seminarian. While another new book—Michael Honey’s To the Promised Land: Martin Luther King and the Fight for Economic Justice—focuses on the radical activism of King’s later years, Parr explores its deeper origins in his “formative time” at Crozer Theological Seminary. Drawing on a variety of sources, including interviews with some of King’s classmates, Parr captures the texture of this often-overlooked season, which stretched from 1948 to 1951, in Chester, Pennsylvania.

The story unfolds chronologically, as Parr chronicles each term of King’s seminary career. He was only 19 and full of boyish mischief when he arrived at Crozer, but by the time he graduated at 22 he was well on his way to being a formidable leader. Parr describes the full diversity of King’s experiences along the way, ranging from a stint on the Crozer basketball team to his tenure as class president his final year.

Many readers will be surprised to learn that King took advantage of the somewhat greater liberty afforded by his northern context and dated a white woman, Betty Moitz. The relationship would not last, but in Parr’s 2016 interview with Moitz, she related, “We were madly, madly in love, the way young people can fall in love.”

Most illuminating is the book’s treatment of King’s intellectual development. As others have shown, he was a serial plagiarizer of course papers. Parr offers extensive documentation of this problematic practice as well as some speculation about why King might have engaged in it, not to mention how he avoided getting caught (although the silence of the evidence on these latter questions makes it impossible to say anything definitive). What is beyond debate, as Parr underscores, is that the plagiarism makes it all the more challenging to trace the evolution of his thought in these years. Nevertheless, by retracing King’s curricular steps, Parr is able to recover an intellectual arc. He includes a chart of King’s classes for each term, complete with their catalog descriptions and his final grades, and describes some of his most influential teachers.

As a visiting student at the University of Pennsylvania, he read Kant, Marx, and Gandhi in a course with Professor Elizabeth Flower. Meanwhile, at Crozer he studied under the likes of Kenneth Smith and George W. Davis, who made sure he was steeped in the writings of Walter Rauschenbusch and Reinhold Niebuhr. The social gospel that King would propound in Montgomery, Chicago, and across the land was significantly honed during his time as a seminarian.

Parr’s book does not mount an especially ambitious argument. But he has done some impressive digging in the historical record and there is no doubt that scholars writing about King will find The Seminarian useful. The book should also attract students and faculty at seminaries and divinity schools, who will be interested not only in the particularities of King’s experience at Crozer but also in the fascinating picture that emerges of a mid-20th-century theological education.

Not until the epilogue does Parr name his desire to “push back against the deification and offer as nuanced a view as possible” of King. But the intent is clear throughout the book. Historians such as Jacquelyn Dowd Hall have argued persuasively that the mainstreaming of a revisionist, sentimentalized picture of King is one of the great victories of the latter-day opposition to the black freedom struggle. The more that Americans forget about King’s bracing egalitarianism, the more he becomes just another high priest in the nation’s civil religion, sanctifying a superficial fairness at the expense of true racial and economic justice.

It is impossible to say at this point whether Parr’s study, along with the others being published on the half-century anniversary of King’s death, will succeed in correcting popular memory. But, swimming as we are in a sea of mis-remembrances, we can certainly hope.