Flannery O'Connor's demonic characters bear witness to Christ

If O'Connor's stories are shocking, that's only because the gospel is, too.

At a Bible study several years ago, I overheard a group of men and women questioning why it’s easier to talk about our successes than about our suffering. My inner theologian wanted to step into the circle and say, “Because we misperceive the subversive nature of God.” We assume that success shows God’s favor toward us, but often the truth is that God’s friends suffer.

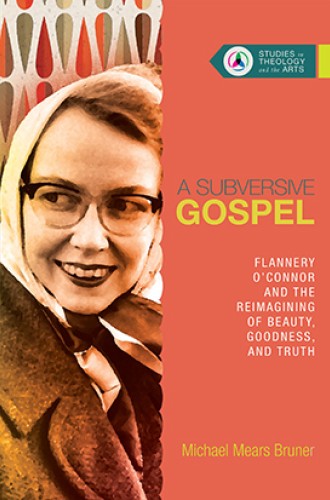

Practical theologian Michael Mears Bruner reminds us of this reality. He counters the modern assumption “that God’s main purpose is to work for the glory, happiness, and satisfaction of humanity.” Instead, the gospel asks us to follow a “bleeding, stinking, mad” Christ. Such a message has always been hard to understand, which is why Bruner relies on Flannery O’Connor’s startling figures and shouting prophets to make his point. Unlike much O’Connor scholarship, which mistakes the stories as ends in themselves, Bruner’s book points beyond the stories to the Christ that O’Connor proclaims.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Bruner talks to readers as a teacher would to students, charitably and approachably. He refutes other critics humbly, acknowledging his own weaknesses as a scholar and admitting his personal biases. Yet this humility does not keep him from debating inaccurate interpretations of O’Connor’s work. The nearly 20 excursuses are fantastic miniature articles that correct problematic readings of her stories and elaborate on fine points that other scholars haven’t considered.

For instance, O’Connor’s style has been considered gothic, and scholar Anthony Di Renzo has compared her freaks to the gargoyles that upset the “aesthetic and theological norms of medieval Scholasticism.” With a handful of medieval experts to support his contention, Bruner insists that “gargoyles were actually the expression, not repudiation, of medieval Scholastic theology and its preoccupation with the demonic.” Bruner’s stance coheres more with the idea that O’Connor was a “hillbilly Thomist.”

The subversive nature of O’Connor’s fiction reflects the Gospels, and Bruner reveals the “implicit scaffolding” of beauty, goodness, and truth in their subversive forms in her work. “Flannery O’Connor’s stories are shocking because the gospel that informed and inspired her stories is shocking. They shock and offend because Scripture shocks and offends. They subvert normal categories because Scripture subverts normal categories.” When O’Connor’s demonic characters, like Mrs. Shortley or Rufus Johnson, quote the Bible or spout theological truths, readers may be horrified. Yet such witness is consistent with the gospel, in which devils recognize Jesus as Christ before the disciples do.

From initial reviews of O’Connor’s work to recent personal correspondence with scholars and unpublished conference papers, Bruner covers an exhaustive depth and breadth of scholarship. Rather than walk through O’Connor’s stories, Bruner assumes the reader has substantial knowledge of them. He devotes most of the book to investigating the methods of O’Connor’s aesthetic and illuminating one of her most overlooked theological influences, Baron Friedrich von Hügel. Countering critics who regard as hindrances the restraints on O’Connor’s life (including her 14-year struggle with lupus, her confinement to the Milledgeville farm for the last third of her life, and her Catholic faith), Brunner posits that these limitations aided her art.

Bruner divides O’Connor’s work into three periods—her earliest stories; the stories produced at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and her first novel, Wise Blood; and her later fiction (including her second novel, The Violent Bear It Away)—and explains the theological transitions between them. O’Connor satirizes in her first novel what sociologist Christian Smith later termed “moral therapeutic Deism.” The word church appears 30 times in Wise Blood and not a single time in her second novel. But it isn’t until after she reads von Hügel’s ideas on the “cost” of faith that she produces the more theologically rich narrative about ascetic love in The Violent Bear It Away.

Bruner notes that words such as “mercy, grace, fire, burn and Lord do not appear a single time in Wise Blood,” which he calls a “novel with more formally religious or ecclesial preoccupations.” In contrast, Bruner reads The Violent Bear It Away as “a case study in subversion.” Instead of aiming at the church as institution, O’Connor portrays violence as more personal and inward. Like Paul, of whom the Lord tells Ananias, “I will show him how much he must suffer for my name,” the hero Tarwater receives a call to walk in the footsteps of Abel and the martyrs.

Bruner helpfully distinguishes between two types of violence in O’Connor’s work, a distinction that has been a stumbling block for many O’Connor readers. Many critics have cast violence as either all good or all evil in her fiction, thus distorting her portrayals of God and the devil. Bruner draws a table to show how some of the violence in O’Connor’s fiction is divinely instituted and other instances are brought forth by the demonic. One notable example is the rape of Tarwater in The Violent Bear It Away. Although God redeems the moment to call Tarwater to himself, Bruner notes that it is the devil who enacts the violence against the teenager, not God.

Near the end of the book, Bruner attempts to respond as O’Connor would to her critics, those enlightened readers who misconstrue her stories as misanthropic or tragic. “People are treated like dirt!” he imagines the critics crying, and he continues: “One can only imagine O’Connor’s rueful response: Because they are.”

Bruner’s witticism reminds me of a gift that my father once gave me, a luminescent cobalt rock. “It’s glass,” he explained, “created when lightning hit the sand.” The rock is something like O’Connor’s stories. Yes, her characters may be treated like dirt, and their moments of grace may cause them pain and shock. Yet O’Connor shows us something true about our nature, our suffering, and God’s grace. When struck by lightning, even dirt becomes beautiful.