Donna Haskins defeats the devil

Onaje X. O. Woodbine’s book about a Black woman’s life is a model of ethnographic work that centers the voice of its subject.

Ms. Donna Haskins appears briefly in Onaje Woodbine’s 2016 study Black Gods of the Asphalt: Religion, Hip-Hop, and Street Basketball. A young man named Jason meets “a lady of God, a voice of God,” who provides counsel after he’s injured in a college basketball game. Later she channels the voice of one of Jason’s ancestors to tell him that he’s meant for greatness and will be a minister of God. Although Haskins is a minor character in the story, Woodbine hints at her larger significance in his analysis of Jason: “Black male athletes cannot achieve spiritual freedom from the hegemonic forces of culture without realizing the ultimate value of women.” He adds, “God may be at the apex of Jason’s hoops theology, but ancestors mediate God’s grace on the court.”

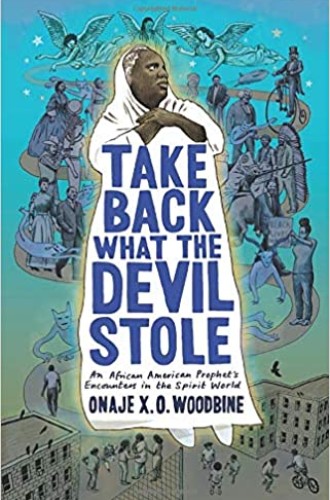

These two conclusions—that women are crucial (and often marginalized) in Black communities and that the living can connect with the dead in tangible ways—emerge fully, beautifully, and startlingly in Woodbine’s second book, Take Back What the Devil Stole, which tells the story of Haskins’s life. It’s a compelling story because it is simultaneously ordinary and extraordinary.

What’s ordinary—and tragic in its ordinariness—is the depth of suffering Haskins experiences throughout her life. Shaped by a childhood in public housing that was designed to be isolated from Boston’s economic opportunities and social services, she endures inadequate public education, sexual assaults, police brutality, substandard medical care during cancer treatment, intimate partner violence, persistent poverty, and the thousands of everyday indignities that come from being a poor Black woman in America.

What’s extraordinary is the agency and healing that emerge as Haskins incorporates new layers of faith into her life. Raised as a Catholic, she experiences something like a conversion at age 46 while visiting her sister’s Baptist church:

The jubilant sounds of the Black gospel choir, the ecstatic shouts of joy erupting spontaneously from Black congregants’ sanctified mouths, and the welcoming gestures of the graceful ushers enclosed Donna in a sensual space of resistance to the hardness of life in the streets of Roxbury. In this new space of worship, she felt her black body had come home. She couldn’t believe that Christians were allowed to incarnate the Holy Spirit in such a full-bodied, celebratory way.

After the sermon, Haskins says, “the joy of the Lord was with me. I walked out. I felt good.” She goes home, cleans her house, tells her cheating boyfriend never to call her again, and commits to a life of prayer and celibacy.

And then her encounters in the spirit world begin. “Through the marvels of her own inventiveness and from the safety of her Roxbury apartment, she becomes aware of an-other dimension, a nonmaterial world defined not, for once, by people’s perceptions of her body.” It begins one afternoon when Haskins lies down after reading the Bible and enters a spirit world where she fights the demon of lust. Soon she encounters other spirits—some good, some dangerous—and starts speaking in tongues. She meets Jesus, who proclaims the forgiveness of all her sins, envelops her in love, absorbs all her sorrow, and fills her with sanctifying power:

His eyes were so beautiful. They were sparkling like light and diamonds. He wasn’t even moving his mouth. Oh my God. I wanted to stay with Him.

He then began pouring love into me. After he had spoken to me, he reached his arms out to me. He brought me into His bosoms, and I felt all this love come inside me, a love that I can’t even express. It’s not a love of this world.

Haskins’s spiritual travels intensify as her Catholic childhood, Afro-Caribbean heritage, and Baptist worship life merge to create a space where she can reckon with the demons—systemic and personal—that have conspired against her for her whole life. The Holy Spirit gives her a new name, Child of Light, and opens portals to other worlds for her. In these realms she meets with St. Michael and other angels, visits her African ancestors, battles witches and demons, soothes the unsettled spirits of murdered slaves and Indigenous people, teleports to places where she can warn people who are in danger, defeats sexual predators, and sees into the future.

Woodbine cautiously entwines his scholarly voice with Haskins’s story, aware of the violence that occurs when Black women’s voices are erased. Although he grew up near Haskins’s apartment, Woodbine now teaches philosophy and religion at a prestigious university. Haskins has trouble reading and writing because of a learning disability that wasn’t discovered until she tried to get a GED as an adult. It would be easy for a book like this to bury the protagonist’s subjectivity underneath the ethnographer’s analysis.

But it’s clear that Take Back What the Devil Stole is a collaborative project. I’ve never read an academic book that so successfully avoids jargon, insider arguments, and unnecessary citations. After a brief introduction, the story unfolds mostly in Haskins’s own words, with only occasional interpolations by Woodbine. Near the end of the book, he writes about Haskins visiting the labyrinths of hell with Jesus as her protector. She recounts seeing a grotesque “thing, a horror” sitting on a throne. When Woodbine asks her to describe the devil further, she answers: “Describing it will give it glory, and I’m not trying to give it glory. God told me only to call it an entity, a thing.” There’s no doubt about who is in charge of the narrative here.

Woodbine’s voice returns fully in the last chapter as he describes reading the entire manuscript aloud to Haskins and asking her to correct or delete anything he’s gotten wrong (which she does at several points). This practice is rooted in his commitment to “combined ethnographic labor” that centers the subject’s voice and experience. If his research subjects can’t understand what he writes about them or if they find any part of it untruthful, the project has failed.

At one point when Woodbine is reading Haskins a part of her story, she responds with tearful gratitude: “When everyone was saying I was crazy, people in my family, you always believed me. Thank you!”

“Her words broke open my heart,” Woodbine admits, noting how his work with Haskins affirmed the value of her humanity: “It meant that she was no longer invisible. It meant that she existed. It meant that Donna’s life mattered.”

I’d like to think that the world will become a little more capacious each time someone who doesn’t share Haskins’s circumstances or epistemology gets caught up in her lived religious experiences. Not because our reading of this book gives her life additional value, but because her life so wondrously testifies to the God whose never-ending love helps us resist the demons of this world and find our value in Christ.