Danusha Laméris’s new book is filled with small kindnesses

A luminous poetry collection marked by joy and sorrow, humor and truth.

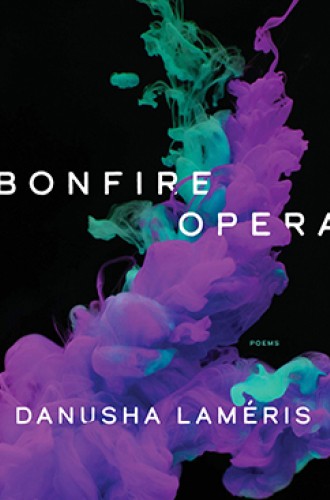

Many readers will recognize Danusha Laméris as the author of the much-beloved poem “Small Kindnesses,” which went viral in 2019, shared by hundreds of thousands of people online and published in outlets including the New York Times Magazine. That short but masterful poem perhaps best encapsulates what her latest collection, Bonfire Opera, accomplishes by using swatches of specific, personal narratives to illuminate universal aspects of the human experience.

One of the most delightful traits of this book is the accessible and conversational tone of her writing. She often begins a poem in medias res, as if speaking with a friend. She starts “Small Kindnesses” with this simple confession:

I’ve been thinking about the way, when you walk

down a crowded aisle, people pull in their legs

to let you by. Or how strangers still say “bless you”

She allows the poem to unfold as a litany of kindnesses—someone stopping to pick up spilled lemons from a grocery bag, the barista handing off a cup of hot coffee, and “the driver in the red pick-up truck” who agrees “to let us pass.”

The list alone might have been enough to make Laméris’s point about the necessity of small social connections, especially at a time like this. But the poem soon opens into what the poet Jane Hirshfield has called a “window-moment,” through which we glimpse a larger truth:

We have so little of each other, now. So far

from tribe and fire. Only these brief moments of exchange.

What if they are the true dwelling of the holy,

Naming these “moments of exchange” feels both essential and reinforcing, and Laméris—in the space of just a few lines—argues convincingly for their continued practice at a time when many of us might struggle with loneliness and isolation. The poem, and indeed the entire collection, invites us to pay closer attention to the people in our immediate lives and the things of our world, no matter how insignificant they might once have appeared.

“Improvement” is another exquisite poem, one that feels tailored to our troubled times. Here, Laméris shows readers that even the slightest good news (“The optometrist says my eyes / are getting better each year”) can become a cause for celebration. When health and well-being preoccupy so much of our thinking, Laméris exhorts us to turn our attention toward the hopeful in our lives, giving thanks for whatever might be going on right at the moment:

So much goes downhill: joints

wearing out with every mile,

the delicate folds of the eardrum

exhausted from years of listening.

I’m grateful for small victories.

Her statements can feel so matter of fact, yet the very simplicity of her language—like that of all memorable poetry—stays with us long after we close the book.

The same can be said of the poems in her first luminous collection, The Moons of August. Yet this second volume represents a leap in richness and complexity that few poets achieve in such a short span of time between books. It is nothing short of astounding that Laméris has earned the wisdom and maturity that mark each of these new poems.

“O Darkness” stands as a prime example of her richly layered narratives. Like so many of the poems in Bonfire Opera, it transforms into a kind of praise song by the end. What begins for the speaker as an appreciation of the color of her skin (“‘My arm is so brown and beautiful,’ is a thought I have“) soon becomes a meditation on our culture’s use of the word dark to stand for the negative. Laméris powerfully points out:

. . . when I seek a synonym for dark, I find dim, nefarious, gloomy,

threatening, impure. Is the world still so afraid of shadows?

Of the dark face of the earth, falling across the moon?

The dark earth from which we’ve sprung, to which

we shall return?

By the time she reaches the final lines (“That / which I cannot fathom. In whose image I am made”), the poem has fully convinced us to question not only our associations with darkness but also our relation to the numinous. “How hidden is the sacred,” she says, “quickening in the dark / behind the visible world.”

If we interpret her words in their largest sense, then we might also see that Laméris urges us to embrace the uncertain, unknown, and unfamiliar as just as sacred as the light. For she knows, as she shows over and over again in this collection, just how often joy and sorrow, humor and truth, can coexist in the same fragile moment.