Consciousness all the way down

If consciousness is universal and the universe is fine-tuned for life, Philip Goff argues, then there must be a cosmic purpose.

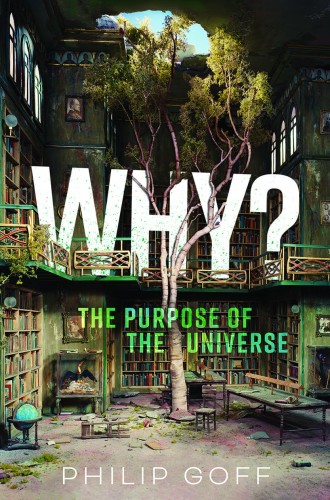

Why?

The Purpose of the Universe

Do trees have minds? A friend posed this question during one of the high school afternoons we habitually spent—no doubt with too much time on our hands—engaging in amateur philosophical banter. It struck me immediately as absurd. Minds require physical brains, I replied, as well as observable behavior that demonstrates the existence of a mind behind it. He was not convinced and responded that trees might have a type of consciousness that is different from ours.

As it turns out, there is a spirited movement afoot among some British and American philosophers, theologians, and a few neuroscientists that takes my friend’s question seriously. The figures in this movement generally hold that, for mind to exist at all, it must be a basic constituent of reality. If mind is as fundamental to reality as matter, it can be inferred that it extends beyond the complex nervous systems of human beings and higher animals and thus belongs, in an admittedly more rudimentary sense, to trees and other plants, to single-celled organisms, to natural bodies like mountains and rivers, to manufactured objects like tables and chairs, and in fact to the elementary particles—electrons, protons, neutrons, and quarks—that make up the universe. This viewpoint, known as panpsychism, declares that consciousness, in some form, goes all the way down.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

For the last hundred years, the dominant position in Anglo-American philosophy when it comes to the nature of the mind has been materialism, the rather dreary assessment of our inner, conscious lives as the manifestation of nothing more than the biological functioning of our brains. In its most extreme form, this view holds that the mind, and with it the self, is an illusion, a trick that the brain plays upon us. The publication of Australian philosopher David Chalmers’s The Conscious Mind in 1996, however, brilliantly called the reigning materialism of the philosophical world into question and changed the conversation. Chalmers argues that theorists can explain “easy problems” of consciousness involving descriptions of our cognitive functioning but not the “hard problem” of why we have any inner, qualitative experience at all. Materialism cannot explain what it is like, subjectively, to be aware, to know, and to feel. Chalmers advances a position he dubs “naturalistic dualism,” according to which everything in the world has irreducible physical and mental attributes. A new generation of thinkers influenced by Chalmers has subsequently embraced panpsychism as a more compelling approach to the stubborn fact of consciousness than theories that try to explain it away.

Philip Goff is a British philosopher who has recently established himself as a leading representative of this line of thought. He has written two celebrated books defending panpsychism, Consciousness and Fundamental Reality and Galileo’s Error. At the end of last year, he released a third book, with the audacious title Why? The Purpose of the Universe. In Why? Goff argues that the universality of consciousness as well as the fine-tuning of the universe for life make an overwhelming case for cosmic purpose.

Goff maintains that consciousness is not publicly observable and evades the explanatory power of empirical science. While our inner experience is mediated through culture and language, objective, scientific means of investigation cannot tell us what it is like to be the particular, conscious beings that we are. We know ourselves, Goff insists, through introspection and possess an indubitable awareness of our inner life, our thoughts, feelings, and sense of personal identity. We therefore possess an “experiential understanding” of the world—what we know as experiencing subjects—that exceeds the “functional understanding” that might be inferred from observations of our external behavior. In Goff’s version of panpsychism, consciousness is also the deep nature of reality and underlies the basic mathematical structures of physics. Physical matter remains, unlike in full-blown idealism, wholly real, but it is also a concrete manifestation of consciousness. The public data available through empirical science must be supplemented by the personal knowledge that comes through consciousness.

Goff maintains that the particles that make up the world have a rudimentary level of agency as well as mentality. Fundamental particles are agents just to the extent that they exhibit the capacities of attraction and aversion—attraction to what they like, and aversion to what they dislike. This rational form of responsiveness is characteristic of matter and energy and is a very primitive form of what living organisms do when they follow their conscious inclinations. At the same time, Goff resists the idea that the complex consciousness of self-aware human beings can be simply reduced to the primitive behavior of conscious particles. The “I” or self is still more than the sum of its parts. Goff predicts that future research will show that human, reflective consciousness is a novel reality in the world that assimilates the rudimentary, conscious particles out of which the world is made and transforms them into a greater whole.

Panpsychism suggests that there is an underlying rationality to the physical world, and this suggestion is supported, according to Goff, by the contemporary scientific discovery that the universe seems exquisitely designed for life. There are several dozen variables within the laws of physics that reveal the universe to be balanced on a razor’s edge between myriad other, chaotic possibilities. For example, the strengths of the four fundamental forces and the masses of elementary particles, if they were only slightly different, would render life in the cosmos impossible.

Goff cites as an instance the strength of the strong nuclear force, which can be assigned the numerical value of .007. If the numerical value had been .006, the universe would contain only hydrogen, meaning the development of complex, carbon-based life forms would not have occurred. If the numerical value had been .008 or higher, hydrogen would never have existed at all. If the cosmological constant, which determines the rate of the universe’s expansion, had been ever so slightly larger, the universe would have expanded too quickly to allow for gravity to coalesce matter and energy into stars and planets. If it had been ever so slightly lower, the universe would have collapsed back on itself before stars and planets could form. If gravity was a little stronger or weaker, or if the universe had begun with a different ratio of matter and antimatter, or in a state of high rather than low entropy, or with a tiny bit higher or lower density, or if it had some other number of spatial and temporal dimensions, it is highly unlikely that life could have formed as well. From the point of view of life, the universe is a miracle.

While cosmic fine-tuning is often invoked as evidence for the existence of God as the fine-tuner, skeptics offer alternative explanations. This includes the argument that our universe is merely one of an infinite number of universes with different physical laws and constants, and our universe’s physical laws and constants, by sheer accident, support life. Yet, as Goff demonstrates, the appeal to a multiverse to explain the remarkable features of our own universe suffers from the “inverse gambler’s fallacy.” In the inverse gambler’s fallacy, one imagines a gambler rolling a pair of lucky dice again and again and then concludes that the other gamblers in the casino must be rolling pairs of unlucky dice. This is a logical error. The presence of other people in the casino has no bearing on the odds that one person will luck out with the dice. Similarly, the possibility of other universes (which, for all we know, might be fine-tuned as well) does not tell us why the one universe we can observe has beaten seemingly impossible odds.

For Goff, panpsychism also entails cosmopsychism, the thesis that the universe itself possesses a conscious mind. Particles, as contemporary physics teaches us, act in networks and are embedded within universe-wide fields. Since these particles, within a panpsychist framework, are conscious, Goff infers that there must be a conscious mind that is the bearer of these networks and fields. This conscious mind—akin to what philosophy since Plato has traditionally termed the world soul—is both the author of the mathematical language of physics and the source of the fine-tuning of the cosmos. Goff speculates that this conscious mind fine-tuned the universe for life in the very first fraction of a second after the Big Bang.

Yet Goff’s version of a world soul is not divine or transcendent. Goff does not believe in the classical understanding of God—what he calls the “Omni-God”—as all-powerful, all-knowing, and supremely good. He cannot accept that such a God would permit the amount of evil and suffering that we see in the world. Goff is open to the possibility of a benign Creator who is simply not omnipotent in an absolute sense. Yet he settles, at least in this book, for a world soul instead. The universe fine-tunes itself rather than requiring a supernatural designer to do so.

Goff infers—from the fine-tuning of the universe, the reality of something like a world soul, and the appearance of rational organisms such as human beings—that the universe has a purpose, an end or telos. Cosmic purpose follows from what Goff calls the value-selection hypothesis: “Certain of the fixed numbers in physics are as they are because they allow for a universe containing things of significant value.” Since the world soul fine-tunes the cosmos for things that are worthwhile, like life and mind, it nevertheless must be attuned to “considerations of value” and driven to “maximize the good.” Goff argues that an overarching cosmic purpose means that we should strive for the betterment of the world as well as ourselves.

Although Goff is agnostic about the existence of God, he nonetheless defends the role of religious communities like the church in encouraging the moral and social transformation that seems to be prefigured by the drive of everything to maximize value. He also considers mystical experience to be significant in helping us to overcome our cultural conditioning and connect with the consciousness that pervades the world. He calls for a spiritual and political movement working for a just society out of “great hope for the future of the universe.” Cosmic purposivism does not support a dogmatic faith but rather one that acknowledges the limits of our understanding.

While Goff is not a Christian in any conventional sense, Christians should welcome the hopeful view of the world contained in the pages of his book, the sense of almost mystical wonder and intellectual adventure that animates his thought, the refreshingly noncombative tone of his writing, and his generous assessment of philosophers and theologians with very different views from his own. At one point in his text, Goff stops and asks the reader, “What do you think?” His book is an invitation to ask big questions and search for the truth but not a demand that one accept all of his conclusions.

However Christians may respond to Goff’s claims, there is much in panpsychism and cosmopsychism that we can ponder for our own contemporary faith. For many readers, process theology will naturally come to mind as a point of entry for Christian conversation with Goff’s philosophy. Like Goff, process theologians reject the classical conception of divine omnipotence as incompatible with suffering and evil, envision the unfolding of the world as a progressive realization of value, and affirm that reality is fundamentally mental as well as physical. The basic units of nature are actual occasions or what process philosopher Alfred North Whitehead describes as “drops of experience.” Because actual occasions are experiential, God can influence or lure them into realizing novel possibilities of greater value, as well as beauty, in the world.

The American process theologian David Ray Griffin, in such exceptional works as Unsnarling the World-Knot and Reenchantment without Supernaturalism, defends a version of panpsychism that he dubs “panexperientialism.” For Griffin, it is experience rather than psyche (mind or soul) which is omnipresent in nature, because actual occasions are momentary, fleeting events rather than enduring individuals like human persons (who technically are complex societies of actual occasions). Griffin does not think that aggregated, inert objects like mountains and trees possess experience but only true individuals.

For those not inclined toward process theism, another fine example of Christian dialogue with panpsychist philosophy is Joanna Leidenhag’s recent publication, Minding Creation. In this book, the British theologian puts forward a theologically orthodox interpretation of panpsychism and weds it to a sacramental and ecological faith. In Leidenhag’s reading of panpsychism, all material things possess interior depth and are thereby open to the transformative power of the divine presence. Our common affirmation of the interpersonal communion between God and human beings in prayer, worship, and a range of spiritual practices is extended, in light of panpsychism, to demonstrate God’s connection with all creatures. God intends to have a personal relationship with everything that exists. God’s Spirit indwells in creation by virtue of its essential interiority and sanctifies all of creation. In a sacramental, panpsychist view of the material cosmos, the world is lit up from within and “all things are indwelt by God.” An invisible presence runs through the visible world.

It is not difficult for Christians to imagine the universe-wide fields that Goff evokes as the territory of God’s indwelling Spirit.

While Leidenhag does not discuss cosmopsychism, the Spirit has sometimes, in the Christian tradition, been identified with the world soul. The Spirit, as the third person of the Trinity, is of course transcendent from the physical world, but she also indwells in the world and displays some of the attributes that Goff assigns to a cosmic mind. The German theologian Michael Welker, in God the Spirit, conceives of the Spirit as a force field that pervades the creation. It is not difficult for Christians to imagine the universe-wide fields evoked by Goff as the territory of God’s indwelling Spirit. The Spirit, who moves over the face of the waters in the opening chapter of Genesis, is for Christians the initial fine-tuner of the universe that Goff takes to be the world soul.

In a famous essay that is now over 50 years old, “The Historic Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis,” historian Lynn White blames the dualism and anthropocentrism of the Christian tradition for the destruction of the planet by Western science and technology. An additional factor is surely the loss of transcendence and the disenchantment of the material world underwritten by secular Enlightenment thought and inscribed within the industrial capitalist order it apotheosizes. Yet Christians must nevertheless own up to the responsibility we share with others for the planetary emergency that is already upon us. White proposes panpsychism, which he associates primarily with St. Francis, as an antidote to the ostensibly exclusive focus of traditional Christianity on the good of humanity over other creatures.

Leidenhag notes the widespread appeal to panpsychism in contemporary ecological philosophy and takes up White’s challenge to envision a more ecologically viable alternative to Christian anthropocentrism. She does this by teasing out parallels between panpsychist and biblical visions of the cosmos. The Bible depicts creation as a sacred theater where the drama of God plays out. It speaks of the natural world in the language of poetry and praise rather than in the mechanistic language of modern science. The Psalms in particular portray the created world as a participant in the worship of God: “The heavens are telling the glory of God, and the firmament declares his handiwork” (Ps. 19:1). Panpsychism lends support to this biblical image of the nonhuman creation as possessing a measure of awareness, agency, and subjectivity. Nature is a congregation whose members join in the cosmic liturgy and respond to the active presence of God.

The panpsychist affirmation of the omnipresence of mind and the biblical vision of a creation bursting forth in praise of God both support an ecological worldview. We can still affirm the special dignity of human beings, created in the image of God with our capacity for reason, freedom, moral deliberation, and heightened self-awareness, while also acknowledging our interconnection with the rest of the living world. Humanity is bonded to nature in both body and soul. Instead of positioning ourselves above the rest of nature, we can embrace our vocation as nature’s representative before God, called to participate in the sanctification of creation and the preservation of its life.

Panpsychism, finally, has ramifications for the Christian hope in a new heaven and a new earth. The future city of God, according to the book of Revelation, will shine without the light of the sun or of the moon, since it will be completely resplendent with the light of God. The divine presence will be seen and felt by all creatures. That matter and energy shimmer already with the light of consciousness offers us a glimpse of a final day when God’s Spirit will illuminate all things. The whole creation bears the promise of its future deification.

The world, considered both now and in an unknown, eschatological future, is fundamentally composed not of mindless particles bouncing around aimlessly in the dark or freezing into a terminal heat death but rather of atoms of praise in the chorus of creation. The deep nature of the material world is a soulful dance that follows the choreography of the Spirit from the beginning of creation to its end. When God summons the elements and the wind of the Spirit blows everything back into existence at the end of time, the groaning of creation will turn into consummate joy, the mountains will drip with wine, the rivers will flow with water, the dead will rise in Christ, and even the trees will clap their hands.