A body in pain navigates the world

Poet Molly McCully Brown’s memoir of life with cerebral palsy

There are voices to which attention is paid, and there are voices that are shunted to the side. The absence of women’s voices from the annals of history, science, poetry, and nearly every other field is news to almost no one. The genre of memoir, however, has been claimed by women—and particularly by White, middle-aged, educated women—following the success of Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love. Some of these memoirs are hilarious, insightful, and gripping. Others should have called it quits at being a magazine piece.

Molly McCully Brown has written a humdinger of a memoir: a collection of essays that amply display her skill with poetry as they tell the story of her body in the world and reflect on how this body and its experiences have formed her. In sharing these thoughts and words, she offers precise, evocative, attention-grabbing images of what it means to navigate a world that didn’t think of your needs when it constructed itself.

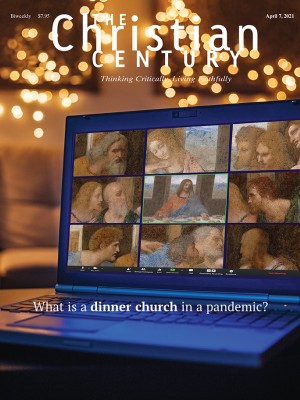

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Brown, she tells us, was born prematurely at a scant 27 weeks. Her chances weren’t good. Her twin sister, Frances (a “small, heated weight [that] is hanging in the air . . . another heartbeat at the furthest edge of your hearing”), died after 36 hours. Brown survived and has lived her whole life with cerebral palsy as a result of oxygen deprivation at birth.

The facts of cerebral palsy emerge over the course of the book: hypertonic and spasming muscles, years of surgeries and casts and braces, difficulty processing patterns and numbers (she flunked math and has a lousy sense of direction), and pain—always pain, small or large.

Along with these facts comes musing, fighting, softening, and formation. Living as, with, and in her body is no linear route to anything tidy. Brown parks her Segway far enough from the Bolognese café that she can sit at a table and be seen as a pretty young woman who could “get up and walk right out of there, painless and fluid and unremarkable,” without fielding comments, questions, or pity. A few minutes later, she feels “guilty as hell for trying to crawl out of my own skin.” She has “a nasty habit of treating my body like it’s a bad suit of clothes or a thing that somehow just keeps happening to me.” Still, she wouldn’t want any other life. She knows the gifts of being gentle with her body, accepting its limits, and surrendering all the places she can’t go at all. Yet she is furious with her body’s resistance to everything she asks of it.

In the end, she knows that her body “isn’t standing apart from me holding my life in a vice grip. It is making my life, indivisible from the rest of me.” Maybe, in the end, the point is not that she arrives at a point of perfect reconciliation with her body, letting go of shame and a lifetime of casual dismissals and assumptions. Maybe, she writes, the point is that she is still alive, “still in the business of heading somewhere.” Maybe there is no perfect reconciliation but “only the way I hold it all suspended: wonderful, and hugely difficult, and true.”

The book is not a unidirectional narrative from hurt to healing. It’s a tapestry of all the threads that weave into a present that appreciates, holds, mourns, and rages against the past. Not just her own past, either. She weaves in visits to the Anatomical Theatre of the Archiginnasio, where European surgery began, which prompts the realization that “I owe the current shape of my body, almost every inch of mobility I’ve ever had, to scores of people taken apart without their consent.” She writes about her relationship with the former Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, only a short drive away from her childhood home. “The more I learned, the less important and extraordinary my own pain seemed. Instead, the history from which my life extends came more sharply into focus.”

One chapter in the book strikes a curiously different note—not necessarily discordant, but with a more journalistic flavor as Brown puzzles out ideas rather than naming the pieces of her own puzzle. In “The Cost of Certainty,” she explores the phenomenon of Jerry Falwell and Liberty University. Raised outside the church, Brown converted to Catholicism as an adult, comfortably holding the beauty and mystery of the liturgy alongside her pro-choice and feminist beliefs. At the core of this chapter is a longing for the certainty she finds so magnetic in the evangelical faith.

This leads to the slightly anomalous feeling that left my brow furrowed and head cocked. In this chapter, Brown does not quite find the same beautifully exact ability to name her own tangled reality. One has the sense that Brown’s attempt to understand “how to hold on to your certain faith even when the way it’s put into practice feels damningly human and flawed” is so current for her that it has not yet crystallized into the clarity she brings to the absence of her twin, her understanding of Jesus, or the complexities of desiring and being desired. This chapter is perfectly interesting, but it does not find the honed precision of the others.

In the end, Brown offers an evocative and lyrically spare glimpse of her world and her life. By offering it in the form she does, she elicits questions about the nature of autobiography and the value of women’s voices. Life is never truly lived as a straight line, so why do we write about it as though it were? Is Brown’s story of herself more valuable because she carries rage instead of self-pity? Does her poetic ability raise her worth above that of another young White woman who does not have the ability to write in such an interesting way? In wanting to commend Brown for not constantly writing about her feelings, am I tossing aside the reality of emotional labor that’s burning out so many people who identify as women?

Brown has most certainly, unapologetically, giftedly found her voice. I hope it will continue to come through, loud and clear.