Why I still love the 1982 version of Annie

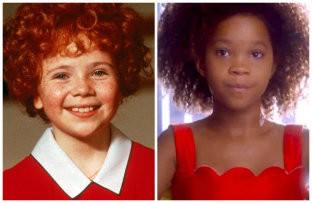

I was as delighted as the next social-justice-minded person to see Annie remade with an African American girl in the title role. But the new version of the musical, which came out this past weekend, doesn't do justice to the surprisingly progressive vision of the 1982 film starring Aileen Quinn—the version I watched and re-watched when I was even younger than Annie's ten years.

I never thought of Annie as a progressive or feminist icon until I watched the classic movie again recently, with my children. The comic strip on which the musical was based—Little Orphan Annie—was created by an an arch-conservative, Harold Gray, who actually killed off Daddy Warbucks during the FDR years because Roosevelt's policies were so offensive to him.

By contrast, in the original film, a bearded revolutionary tries to assassinate Daddy Warbucks the first night Annie stays with him. "He's living proof that the American system reallly works and the Bolsheviks don't want anyone to know," Warbucks's secretary tells Annie. Or maybe, just maybe, those Bolsheviks are standing in solidarity with the ragged, hungry children who swarm around the Rolls Royce when it pulls up in front of the overcrowded and dirty orphanage.

Annie doesn't seem to buy the secretary's explanation. Instead, she manages to get Warbucks to take her to visit FDR, insists that Warbucks should at least respect the president for the office he holds (what an idea!), and helps Roosevelt convince Warbucks to use his business acumen to help organize the work programs of the New Deal. And with her sweet conviction that "the sun'll come out, tomorrow," she helps restore hope for a nation that had plenty to fear, including fear itself.

Annie's not just interested in national influence. She's also a strong and indominable spirit. Freaked out by a nightmare? Call for Annie; she’ll tell you sweet stories to comfort you. But she’ll also threaten to punch your lights out if you kind of deserve it—whether you’re bullying a younger child, abusing a dog, or standing in the way of the New Deal.

And Annie also knows how to organize for subversion. The hilariously evil Miss Hannigan (played, in the original film, by the truly inimitable Carol Burnett) has no power to crush the spirits of Annie and company, because they've got each other—and a great sense of solidarity and fun. They know how to depend on one another.

Yet as I watched the original Annie again, I realized how wonderful it is that Miss Hannigan, a love-starved woman struggling with substance abuse, is redeemed in the end. I used to hate the denouement, when Miss Hannigan appears, beautifully dressed, riding an elephant in the circus that’s happening on Daddy Warbucks’s front lawn. Why wasn't she in jail!?

But really, isn’t Miss Hannigan just an overworked, under-supported social service provider? If you were charged with the sole and entire responsibility for one or two dozen girls, you might be hitting the bottle and ripping heads off baby dolls, too. And even if she made some mistakes, she really didn’t want Annie to die.

As a child I wanted to see her behind bars; I was all about retribution. Now I’m so glad to see her integrated into the happy ending: restorative justice.

If you watch the original Annie closely, you'll see that tough, optimistic little Annie never actually believes her parents are alive and planning on retrieving her one day, with the piece of the broken locket in their hands. “My parents are dead,” she says to the even littler orphan, Molly, to whom she’s a great big sister. Annie confesses to Daddy Warbucks that she’s known all along that they were dead, but she wanted to believe that she was different, that she was special.

He wants to be different and special, too—to believe that he needs and loves only money and power and capitalism, not children or dogs or family. They’re both wounded and they both know it, and it’s only when they stop with the empty "power of positive thinking" nonsense that they actually can be “together at last, together forever.”

It’s hard to tell the truth, to admit your brokenness and need. But they do, and it makes them whole. It fills in the missing piece of that heart-shaped locket.

The original Annie is not just a story of Annie’s journey from rags to riches, or a sentimental tale of billionaire-finds-his-soul. It’s a spacious tale of redemption, one that even makes room for Miss Hannigan. And though Annie’s the star, she doesn’t forget her friends. They’re there, too, dressed in new clothes, hair brushed and shining, a part of the celebration, knowing they’re not about to be left out in the cold again.