Decoration Day

As a child in Wisconsin, I looked forward to Memorial Day for the family reunions. At full sail, with 20-odd aunts and uncles and all their kids, this became a considerable event, complete with dirt-bike riding, beer-fueled volleyball and lots of laughter.

Eventually I came to understand that Memorial Day is related to military service. My grandfather was a tail-gunner during World War II; he was shot down over the Aleutian Islands and again over German-occupied Europe. He was taken prisoner the second time and escaped the camp, crossing Allied lines a month before V-E Day.

These stories, which I knew only in their outlines, thrilled my boyish sense of adventure and swelled my sense of family pride (though my grandfather once got in trouble for giving my brother his service revolver, unloaded, to play with in lieu of a toy gun). Only later did I come to understand the more difficult meaning of Memorial Day.

Long before it became the long weekend marking the beginning of summer and even before it became a generic day to honor veterans, Memorial Day emerged from the many local Decoration Day observances in honor of the Civil War dead. The sheer number of people to be commemorated--unequaled in American history before or since--called forth new ways of honoring the fallen and interpreting their death. Public speeches, parades, picnics in cemeteries, and flowers for the graves were among the ways we gave meaning to a common loss beyond imagining.

“Civil War carnage transformed the mid-nineteenth century’s growing sense of religious doubt into a crisis of belief,” writes historian Drew Gilpin Faust, and a “more profound doubt about the human ability to know and to understand.” Commemorating the dead with peculiar pomp and solemnity was an adaptation to this crisis, she explains. “The meaning of the war had come to inhere in its cost.”

There is nothing new about decorating the graves of the honored dead. Augustine recalls his pious mother’s habit of visiting the tombs of the Christian martyrs to bring gifts and libations in their honor--a custom that bore some resemblance to earlier pagan practices. As America has moved away from any centering religious identity, our war dead are the only publicly approved martyrs we have left. As any pastor who has attempted to put a little reverent space between the altar and the parish flag can tell you, the memory of wartime losses and our attempts to give them meaning live on with a sacred ferocity.

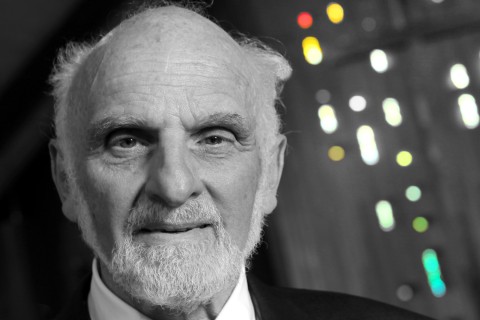

What’s more, it’s hard to even think clearly about policy questions when these memories are involved. I’m among those who favor a speedy withdrawal from Afghanistan, yet I’m plagued by the thought of what this would mean for those lives already--and still to be--lost. I know this is a logical fallacy. But I think of my grandfather, now ten years gone, who was no hardline nationalist and no fan of war, but who wanted very badly for the sacrifices he’d seen firsthand to be acknowledged and remembered as honorable.

But I also think of the toll the war took on him until his last days. Lee Sandlin writes this in his essential essay on the subject:

In the decades after the war ended there probably wasn't a single night in which thousands of men across America didn't wake up sweating in terror. . . . The war was still being fought in a thousand glimpses of torment, in a million flickers of horror.

I was told as a boy that my grandfather had nightmares. The rest--or part of the rest, anyway--I would learn much later.

We have contradictory feelings about our veterans. We enjoy video games filled with raw and vivid depictions of combat. Yet we seem to shy away from those who actually live through battle. Young veterans face an elevated unemployment rate, which some advocates link to job discrimination. We surround the fallen with glory and honor, but we have less to say about the 75,000 veterans who are homeless on any given night.

That is the danger of making veterans into our secular saints. The saints, martyrs and pagan heroes don’t need our compassion or our efforts to give their deaths meaning. They died fully rewarded. Our duty to those who serve is different. “I desire steadfast love and not sacrifice,” God tells Hosea.

Decorating the last resting places of the fallen is a fine and decent thing to do. It is especially fitting when we have done all that we could to keep those graves empty in the first place.