Advent is a season of sighs, especially this year

We don’t pine for a second coming that will bring the world to an end. We pray for the indwelling of Christ that will enable the world to continue.

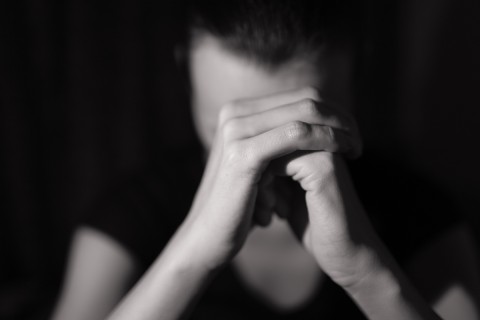

Before Advent is a word, it is a sigh. A voice crying. A mood. And never more deeply felt than in these troubled months. Advent marks both the exhaustion and the hope of God’s people, when the meaning of our lives is expressed in a weary exhalation of ordinary breath and then a sharp intake of something greater.

The prayers and hymns of this season begin with an inarticulate plea for deliverance. It was first voiced not by a hymn writer but by a prophet: “O that thou wouldst rend the heavens and come down” (Is. 64:1). It is in this eighth-century prayer: “O Key of David . . . you open and no one can close; you close and no one can open. O come and lead the captive from prison; free those who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death.”

“O . . .” We are grieving this Advent, which is not like us this close to Christmas. For preachers, the usual challenge of the season is to hold Christmas cheer at bay so as to allow Advent to retain its own brooding character. This year I have a feeling that won’t be a problem. I think we will linger in Advent this year. The Jesuit Gerard Manley Hopkins captures the depth of our grief in his poem “Spring and Fall.” It is addressed to a sad little girl named Margaret: