Pope's visit to Chile met with protests, anger from abuse survivors

Many Chileans are still furious over Francis appointing a bishop who was connected to a notorious abuser.

During Francis’s first visit to Chile as pope, he addressed the country’s clergy sexual abuse scandal while also facing fierce criticism for his response to that issue.

The Argentine pope studied in Chile during his Jesuit novitiate, and he knows the country well. But Chileans gave him the lowest approval rating of the 18 Latin American nations in a recent survey.

Several churches were set on fire in the days before and during his visit, including one that burned to the ground in the southern Araucanía region. Francis celebrated mass in the region on January 17.

Police used tear gas and water cannons to break up a protest during a big open-air mass in the capital, Santiago. They detained several dozen demonstrators, according to an Associated Press photographer at the scene. Some protesters carried signs reading “Burn, pope!” and “We don’t care about the pope!”

Despite the incidents, huge numbers of Chileans turned out to see Francis, including an estimated 400,000 for his mass. Visiting a women’s prison, he brought some inmates to tears. But his meeting with abuse survivors was what many Chileans most awaited.

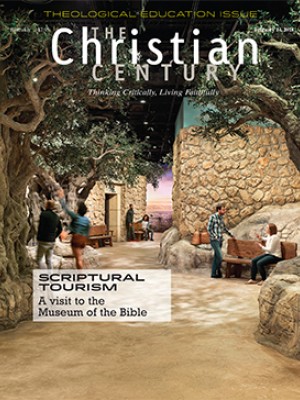

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Vatican spokesman Greg Burke said Francis “listened to them, prayed with them, and wept with them.”

Earlier in the day, Francis told President Michelle Bachelet and other Chilean officials that he felt “bound to express my pain and shame” that some of Chile’s clergy had sexually abused children in their care. “It is right to ask forgiveness and make every effort to support the victims, even as we commit ourselves to ensuring that such things do not happen again.”

Francis did not name Chile’s most notorious pedophile priest, Fernando Karadima, who in 2011 was barred from all pastoral duties and sanctioned by the Vatican to spend the rest of his life in “penance and prayer” for sexually molesting minors. Nor did Francis refer to the fact that the emeritus archbishop of Santiago, a top papal adviser, has acknowledged he knew of complaints against Karadima but didn’t remove him from ministry.

Survivors went public in 2010 with accounts that Karadima had kissed and fondled them when they were teenagers.

Many Chileans are still furious over Francis’s decision in 2015 to appoint Juan Barros, a Karadima protégé, as bishop of the southern city of Osorno. Barros has denied knowing about Karadima’s abuse, but many Chileans don’t believe him and his appointment has split the diocese.

For his part, Barros, who concelebrated an open-air mass with Francis and other bishops, repeated his assertion that he knew nothing of Karadima’s crimes.

“Many lies have been made about me,” he said.

Two days later, in response to a journalist’s question, Francis said that he has seen no evidence that Barros was complicit in covering up the sex crimes of Karadima.

“The day they bring me proof against Bishop Barros, I’ll speak,” Francis said. “There is not one shred of proof against him. It’s all calumny.”

Juan Carlos Cruz, one of those who came forward with an account of abuse by Karadima, wrote on social media: “As if I could have taken a selfie or a photo while Karadima abused me and others and Juan Barros stood by watching it all. . . . the pontiff talks about atonement to the victims. Nothing has changed, and his plea for forgiveness is empty.”

The Karadima scandal and its long cover-up has caused a crisis for the church in Chile, with a recent Latinbarómetro survey saying the case was responsible for a significant drop in the number of Chileans who call themselves Catholic, as well as a fall in confidence in the church as an institution.

“People are leaving the church because they don’t find a protective space there,” said Juan Carlos Claret, spokesman for a group of church members in Osorno that has opposed Barros’s appointment as bishop. “The pastors are eating the flock.”

Francis spoke to hundreds of priests gathered in Santiago’s cathedral, telling them that he knew the scandal had caused pain not only for abuse survivors but in the broader church community and in anyone who wears a clerical collar. He noted that some priests had been insulted in public and that in wearing clerical attire they “paid a heavy price.”

It was similar to the message that Francis delivered to American bishops in 2015—one that infuriated survivors who accused the pope of drawing an equivalency between the trauma that they endured and the pain of clergy when looked upon with suspicion.

“Sex abuse is Pope Francis’s weakest spot in terms of his credibility,” said Massimo Faggioli, a Vatican expert and theology professor at Villanova University in Philadelphia. “It is surprising that the pope and his entourage don’t understand that they need to be more forthcoming on this issue.” —Associated Press

A version of this article, which was edited on January 29, appears in the February 14 print edition under the title “Pope’s visit to Chile met with protests, anger from abuse survivors.”