The Black Church Food Security Network aims to heal the land and heal the soul

“Food charity is a sweet siren song. It is not a sustainable track toward the Beloved Community.”

Heber Brown III, pastor of Pleasant Hope Baptist Church in Baltimore, Maryland, is the founder of the Black Church Food Security Network, through which Black churches and Black farmers are seeking to create a food system that builds on the strengths of the Black community to improve the health and well-being of African Americans.

You began with a church garden. What inspired you to start a garden at Pleasant Hope?

It came out of my work in congregational care. As I was visiting church members in the hospital, I started to recognize a pattern in the nature of my congregants’ hospitalizations: there was often a diet-related issue at the core of why they were struggling.

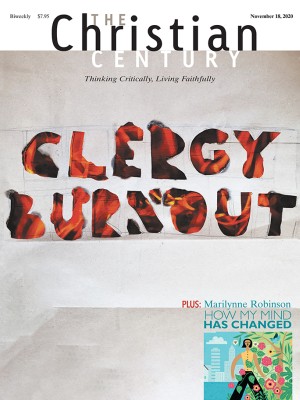

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

My initial thought was to partner with a fresh food market located across the street from our church and maybe work something out to offer fresh food to church members. But when I went over there and walked through the produce aisles, I experienced sticker shock. I couldn’t afford it, and I knew the people I shared life with at the church couldn’t. I didn’t even stay to talk to a manager. I left the market because the price was too high, in more ways than one: I didn’t want to introduce my congregation to yet another food charity initiative.

I walked back to my church, and then I saw a little patch of land near our front door that I had walked by hundreds of times. At that moment, with divine discontent bubbling up from within, God showed me a vision of using that land to establish a garden—with the thought, If you can’t afford what they have, roll up your sleeves and grow it yourself.

Why did you not want to start a food charity initiative?

Charity does not equal justice. Charity can mask our understanding of the root of the problem. Prolonged engagement with charity can corrode the soul of those in need; it can wear away our sense of human dignity, our somebody-ness. The flip side is that when economically affluent, often White-led organizations are constantly in the posture of giving, it can also corrode the soul of the giver, who is always in a position of superiority. Food charity is a sweet siren song. It is not a sustainable track toward the Beloved Community.

You started a church garden, but had you ever done any gardening?

No. Very little. My grandparents are from rural Virginia, so when they came north during the Great Migration, they brought their agrarian wisdom and experience with them. My grandmother would take me and my siblings out into the backyard and get us to pick peas and beans. Only after getting active in this ministry did my mind think back to those days. I recognized that I had a tie there that I was not fully honoring.

I didn’t go into this with a lot of experience. It was a step of faith. I just said, “Here’s a problem. Here’s a step toward solving it. Let’s all bend our genius in the direction of this land and see what it can do for us.”

Where did help come from?

I had overlooked that many of the people in my congregation had grown up down south on farms. They were part of the Great Migration. I’ve studied the Great Migration. I’ve read books. It’s my personal history. But I had never connected the dots. I had never seen the ministry implications of the Great Migration on the local church. I thought it would be the young adults who would become foot soldiers and lieutenants in this work. But it was the seniors. Young adults came on launch day. They helped put in the raised beds and took some great pictures. But gardens need attention every week. That came from the seniors.

Maxine Nicholas was chief among those who led the way. Now, you know Maxine Nicholas—a little sweet lady who gets things done. People listen to her; she’s done a little bit of everything around the church. Pastors know not to get in her way. She was the general. She organized her peers to join in as well. It was a game changer. Sister Maxine passed in November of 2018, but the garden’s name is Maxine’s Garden.

How did the ministry develop from a church garden to the Black Church Food Security Network?

We were growing 1,100 to 1,200 pounds of produce every season. We were giving the produce to anyone in our congregation or anyone who came to the church. We saw our Sunday morning attendance increase. My ego wanted that to be about my preaching, but it was about broccoli and spinach and kale. We used our multipurpose room as a market space. Sister Maxine was very skilled at canning and preserving, so we also provided chowchow and peach preserves.

I started analyzing the ministry. What would it look like if we could help other churches to do the same thing? What if they weren’t just churches in silos growing on their own but were actually being strategic to the point where we had a community-led food system?

The quandary in which we found ourselves was systemic. As much as people liked to place the spotlight on behavior—you are eating the wrong thing; you need to cook that differently—I saw that there are many people who don’t have a grocery store in close distance to their homes. It’s not a coincidental thing. It involves public policy, public decision making. It is a systemic problem, and systemic problems need systemic solutions.

How did you begin to work systemically?

A turning point was when I went to the Civil Rights Museum in Birmingham. I saw something I had never learned in grade school. During the Montgomery bus boycott, the African American community did not just stop riding the buses. They created their own transportation system. Churches in the community bought buses, they coupled that with local folks who were ferrying people around on their own, and they created their own system.

The mayor of Birmingham at that time, Arthur Haynes, said that since Black people were being so unfair to the White merchants, who had never done them any harm, the city was going to cut off payments to the city’s food surplus program—to prove to the Negroes of the community who their true benefactors were. For me, it was an aha moment about the limitations of charity. When you are dependent on the benevolence of another community, you leave yourself vulnerable.

I also studied Fanny Lou Hamer. She was very active toward the end of her life in farming and in helping families figure out how to take care of themselves. She observed, famously, that food is used as a political weapon. But if you have vegetables in your garden and a pig in your yard, then you can feed yourself and your family and nobody can push you around.

Why did you embed the initiative in the Black church?

No other institution has the track record and credibility in Black America. And the Black church community, broadly considered, is the largest landowner in Black America. No one in recent times has considered how much land Black churches own, how many commercial kitchens, how many passenger vans that go largely underutilized Monday through Saturday. That is an enormous amount of resources.

I am really passionate about asset-based mapping and planning. Instead of starting with what you don’t have, start with what you have in your hand. For us, it was 1,500 square feet in the front yard. Starting with what you don’t have is not magnetic energy; it doesn’t get people excited. It doesn’t allow you to dream bigger.

We start with an asset-based theological construct. In Exodus 4, Moses is given a charge to confront Pharaoh and to tell the people that it is time to get free. As Moses expresses hesitation, God asks Moses, What is that in your hand? I know you are telling me what the Pharaoh is going to do and that the people are not going to believe you, but what is that in your hand? Start with that.

Black churches have hard assets and spiritual currency and connection to the community. Let’s use those to create a systemic response—so that even when Heber Brown is dead and gone, the systemic response will live. I wanted to put this in a place that had an infrastructure and a track record of sustainability to carry this far beyond my lifetime.

What happened next?

At first this idea just rolled around in my head. In January of 2015, I had a meeting with a farmer and a public health professional and pitched this idea of a Black church-led food sustainability project. Six months later, after Freddie Gray died in police custody, people started demonstrating and Baltimore was closed down. Our phone started ringing at the church because our calling card was food. People knew: that’s the food church; that’s the garden church.

There were neighborhoods where the corner stores were closed—and that was the only source of food. These were neighborhoods where things were bad before the first brick was thrown. So our church became a command center. Alia, the farmer I had been speaking with, called her farmer friends. They started bringing trucks of produce to Baltimore. We piled up the food on our church bus, and I drove it around the city for two and half weeks. I would go to the corners where demonstrations were happening and set up on the corner.

After a couple of weeks of seeing Black farmers working with Black churches and the Black community, I realized that the idea I had was in motion. At that point, I named it the Black Church Food Security Network.

What are its elements?

We called our first initiative Operation Higher Ground—to seed church gardens. We hired a garden coordinator, and church gardens started popping up around the city. Pastors would usually call me and say, “Heber, we heard about that thing you doing.”

After the gardens came our Soil to Sanctuary markets. For the past two years, we’ve hosted mini farmer’s markets inside the churches, mainly in our church and a few other small pilots. The first Sunday of the month is when we have our markets. That is the weekend when people have the most money to do their grocery shopping. After the benediction, the church goes out to the multipurpose room, where there are six to eight vendors lined up ready to receive folk.

For about three years, we were just giving produce away. Then we did a donation system. Then we moved to a pay system, because we recognized that this was a ministry stream that could potentially pay for itself and we could build our sustainability muscles still further.

Once we realized that we could beat the local market’s prices, we felt better about it. We told people, “You are going to go spend money somewhere. We feel like not only is our product better, but we can introduce you to the person that grew it. You can be supporting a just cause, buying from this black farmer on purpose.” Once we recognized those things, it was not a difficult transition to a pay system. And if someone doesn’t have money, it isn’t like we are turning people away. They are going to get what they need.

Our farmers tell me that they make more money in two hours at the church than they do in six hours downtown. We work hard to do relationship building, and it really has a community feel.

Tell me about the spiritual component of the work.

Our process includes ceremony on the land that is about getting reconnected; I call it being re-membered. We circle up before the garden is planted, after the funds have been raised and the promotion has been done. We have the seeds and the tools and the soil all lined up and ready to go. We pray, we sing, and we testify about our hopes and aspirations for the garden. We tell stories about our upbringing and its relationship to the land. We spend some time in that sacred space of listening and sharing. We pour water, a ceremony called libation, where we name our ancestors and those on whose shoulders we stand.

The African American community has suffered so much from disconnection to the land. Fourteen million acres of land were taken from black farmers in the 20th century. In 1920 we had 15 million acres, and today that number is about 1 million. There are stories in our community of families being run off their land by the KKK. The trauma associated with things like that have led many to distance themselves from farming. The trauma goes from generation to generation.

So part of the work is to show that the land was not the violator—the land was the site of the crime. This effort is an attempt to reclaim what was taken from us, not just in terms of tangible land but also in terms of agricultural legacy and heritage and identity.

Spirituality in the Black community was injured by way of this wickedness that took our land and divided our families. You can’t heal that until you face the demon and name it. So when we go to the land and call our ancestors’ names and put our hands in the soil, my prayer is that it reactivates that connection; I pray for a reawakening and a recognition of that being holy ground.

What was the next initiative?

The phone is ringing off the hook. Churches and denominations are calling from around the country. We heard from the African Methodist Episcopal church. A bishop called and is wanting to have all of the churches in his network involved in some way. So we plan to continue to grow and connect churches. We have hired some field organizers now in Ohio and North Carolina.

What I love about this is that no matter where you are, if there is any kind of an African American community, there is a church somewhere. So we have potential satellite locations all over the country. And given the challenges with climate change, given the economic situation, given what we are facing right now with the coronavirus, we have a community-led emergency response system in place.

I remember vividly who was left on the roof during Hurricane Katrina. That drives our emergency response. Sometimes I feel like Noah building an ark. In our ministry context, we have some tools in our hands.

What is your favorite book about food?

Monica White has a great book called Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement. She writes about Fannie Lou Hamer, George Washington Carver, and Booker T. Washington. She is a brilliant writer on the history of all this.

What’s your favorite food?

Macaroni and cheese.

That’s a funny answer for a church farm guy.

We put the soul in it.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Black churches tackle food insecurity."