A liturgy for people affected by suicide

One person told me, “It’s the first time I’ve been in a church for 30 years, since that day.”

The vision statement of St. Martin-in-the-Fields is: “At the heart. On the edge.” This says something most obviously about geography and culture, but more subtly about faith and life. St. Martin’s is at the heart of London. And for all our identification with the outcast, it’s at the heart of the establishment: it sits half a mile from 10 Downing Street, three-quarters of a mile from Parliament, and a mile from Buckingham Palace. Members of the cabinet and the royal family visit almost every year, and countless famous people come at some stage to celebrate, to honor, or to mourn.

In addition to indicating something central in relation to geography and culture, the word heart refers to feeling, humanity, passion, and emotion. It means the arts, the creativity and joy that move us beyond ourselves—and beyond rational thought—to a plane of hope, longing, desire, and glory.

More importantly, “At the heart” refers implicitly to life, the universe, and everything. For Christians, the heart of it all is God’s decision never to be except to be with us in Christ. That decision gives rise to creation, as a place for God to be with us, incarnation, the moment Christ becomes flesh among us, and heaven, the time and space in which God is with us forever. As a church, St. Martin’s exists to celebrate, enjoy, and embody God being with us—the heart of it all. We’re not about a narcissistic notion that we are the heart. We rest on the conviction that God is the heart and we want to be with God.

The word edge speaks of the conviction that God’s heart is on the edge of human society, with those who have been excluded, rejected, or ignored. God looked on the Hebrews in slavery, looked on Israel in exile, looked on Christ on the cross, and walks with the oppressed today. But St. Martin’s isn’t about bringing those on the imagined “edge” into the exalted “middle.” It’s about saying we want to be where God is, and God’s on the edge so we want to be there too. A former archbishop said, “If you ever lose your sense of the intensity and urgency of faith, go and hang out with those who still have it—and the chances are they’re among those the world regards as the least, the last, and the lost.” That’s why we’re on the edge: because we want to discover that intensity and urgency for ourselves.

Over the years, St. Martin’s has developed what might be termed sharp-end pastoral liturgies for some of those on the edge. We’ve had a service for families of the missing, and a commemoration of those who have died homeless. We’ve also developed a liturgy to support those affected by suicide.

These services illustrate that liturgy is not a synonym for stiff, hidebound, traditional, reactionary, precious, repetitive, wooden performance carried out by prickly, fussy, obsessive people going through the motions without spirit or truth. It is, historically, from classical Greek times, the leitourgia, a public event or gesture carried out to enhance the common good. In Christian usage, it is the sequence principally of actions and secondarily of words that embody and portray the way the church relates to the God of Jesus Christ and is transformed by the Holy Spirit.

In 2014, St. Martin’s was approached by the Alliance of Suicide Prevention Charities to explore the idea of holding a service to stand in solidarity with those affected by suicide. It quickly became apparent that we would be reaching out to three kinds of people.

The first and most visible were parents of those who had, mostly in their late teens and early twenties, and often after a long struggle with mental health challenges, taken their own life. The second were other family members—spouses, siblings, children. What set the parents apart from other relatives seemed to be that the parents were more likely to have founded charities or in some other way become active in supporting other families or advocating for measures to make suicide less prevalent.

The third group we had in mind were those who had themselves attempted suicide, often more than once, and had reached a place where their life was no longer in the same degree of crisis and were willing to speak about what they had been through and offer support to those whose stories had worked out differently.

From the beginning of the conversation, I was aware that these were groups of people who might well have misgivings about the church. Some might feel that churches were full of self-righteous, “together” people who might have little sympathy or tolerance for those whose lives were so evidently troubled or had been so manifestly scarred. Others might simply not share Christian convictions about forgiveness and eternal life and might find themselves uncomfortable around those who did.

A more significant concern might be that suicide has often been condemned among the churches. Roman Catholics who had died by suicide were until recent decades denied a church burial, and the Catholic Church still officially regards suicide as a mortal sin. In these circumstances, the concern of families in approaching a church is understandable. What made St. Martin’s a suitable venue was not simply the dignity, size, and accessibility of the building, but also the congregation’s reputation for humane and sensitive understandings of a whole range of pastoral issues.

The instigator of the service, David Mosse, names the issues succinctly:

Love, it seems to me, is why suicide is so difficult and so utterly painful. Love is that human condition which means that we none of us own ourselves, we have and are shared selves. Suicide is an act within this world of relatedness—often in response to unbearable emotional pain rather than the desire to abandon us—but which tears apart and contradicts what is essential to our very being.

And the damage is long-lasting. As Simon Critchley puts it:

When someone dies by suicide, those bound by love often experience a shadow of the pain and anxiety that preceded the death they grieve; and the guilt. Guilt because, in the search to understand why, we are so connected that we make ourselves the first accused. As we continue our search for answers, suicide saddens the past [at the same time] as it abolishes the future.

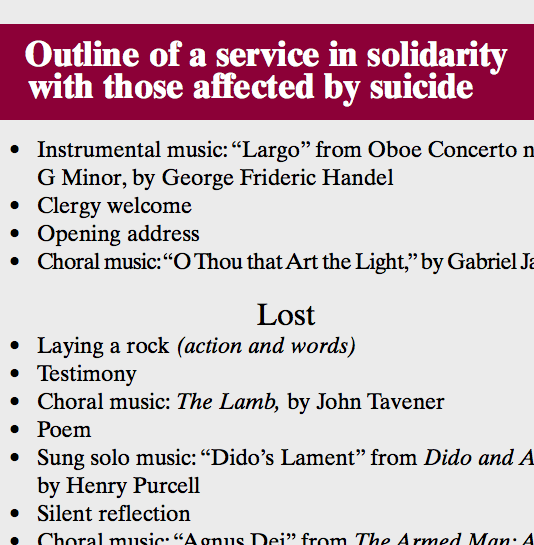

The service that we developed has remained very similar in structure each year. Like most liturgies, it traces a journey, in this case, one in three parts. The first part takes seriously and attempts to meet head on the dismay and horror of losing a loved one to suicide. It speaks the language of lament, testimony, and pain. The second part addresses the more ambivalent experience of attempting suicide and surviving to tell the tale. It articulates what is going through the mind of a person in crisis, but also how those thoughts can be modified and even healed. The third part tentatively hints at solace, in wisdom if not in joy, in solidarity if not in closure, in goodness if not in transformation.

In Mosse’s words, the first part concerns “the loss of self, of connection, of meaning, or of hope that precedes suicide; and the unbearable loss faced by those bereaved.” The second part he describes as “the experience of fear and isolation, especially that inner isolation of those in despair; and the guilt after loss that blocks the path to self-care.” The third part is about “finding the strength to endure, to heal and find purpose, and to help ourselves out of solitude, especially through reaching out to one another.”

To accompany each stage there is a threshold action, paired with suitable words. At the first threshold (“Lost”), a rock—heavy, sharp, uncompromising—is laid down, and these words spoken: “In these rocks we see brokenness, harshness and pain. We see love cut off, a statue destroyed, a future shattered.” At the second threshold (“The Valley”), a candle is lit—fragile, small, yet burning—and these words are spoken: “In this candle flame we see fragility, possibility—the shadow of what is half-known, half-understood, still mourned.” At the third threshold (“Found”), a rose is laid down—beautiful, prickly, tender—and these words are said: “In this rose we see gentle beauty, still with thorns that pierce, yet deep tenderness, hopefulness, deeper truth.”

Silence and music—choral, instrumental, solo, contemporary—are at least as significant as anything spoken or enacted. To hire outstanding singers and musicians isn’t within everyone’s budget, but for the poignancy of an occasion where words cannot ever cover the range of emotions involved, music is vital. Congregational participation in such an environment—which must remain hospitable to people with diverse and often complex feelings about faith—needs to be handled with care. One hymn with a haunting tune seems to be about right.

It’s important to offer serious but gentle words of welcome, such as these:

We’ve gathered today to talk about something that usually evokes silence—silence of shock, pain, terror and loss. We’re gathered to stand in solidarity about something that often keeps people isolate—in despair, grief or guilt. We’ve gathered to find hope together that we perhaps struggle to find alone.

Besides compelling testimonies and helpful readings, two spoken contributions are given prominence. At the beginning is an address from the key person responsible for bringing the service about, speaking from the heart about the experience of loss but also from the head about the nature of suicide and the approaches to its prevention, and setting a reflective and tender tone for all that follows. At the end is a clergy address. More than most sermons, this is about tone of voice more than content, about compassion and understanding rather than proclamation or exegesis. One year I talked about the film Lion and how it addressed issues of loss, depression, failure, isolation, identity, and narrative. Another year I spoke about silence, touch, and words as a response to grief. Another time I explored what it means in the words of Isaiah 43 to be precious, honored, and loved.

Vital to the whole event is the opportunity to gather informally afterward over coffee. It’s a unique pastoral moment. Small talk is unnecessary—everyone is there because their lives have been shaped forever by suicide in some way. Conversations emerge rapidly and honestly. For many it’s a cathartic moment. Some have traveled far simply to be present. Others have never been in a space where their tragedy has been addressed with kindness, understanding, and beauty. After one service a person said to me, “It’s the first time I’ve been in a church for 30 years, since that day.”

One thing that became apparent was that the experience of the person who has considered, perhaps attempted, but nonetheless emerged from the shadow of suicide is very different from the experiences of those bereaved by suicide. The first is a story from despair into hope; the second is a story of grief that may not be helped by premature words of superficial consolation.

More than anything, the service is an opportunity to overcome isolation. Again, to quote Mosse, speaking of his lost son:

Understanding why he, and so many like him—facing incomprehensible pain and despair—felt that to die was the only solution; and making other solutions more thinkable and accessible for those in this desperate state, is the challenge we all face. This is a challenge made so much harder by the stigma and silence that allows suicide as an option to grow in the dark corners of tormented and isolated minds. This perilous silence has to be broken. It really is “time to talk about it.”

Read the author's outline of the service he describes here.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Liturgy at the edge of life.” It was adapted from Samuel Wells's forthcoming book, Liturgy on the Edge: Pastoral and Attractional Worship © 2019 Church Publishing, New York, NY. Used by permission.