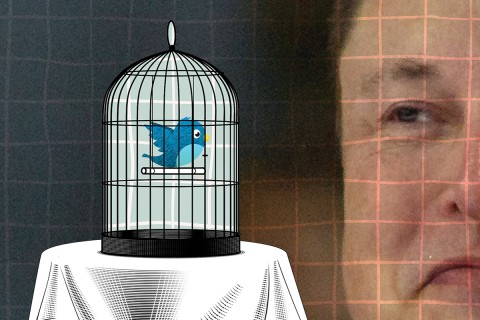

Under Elon Musk’s authority

Doing church on social media is not like standing in the public square. It’s more like putting ourselves under a form of sovereignty.

Last week Elon Musk, owner of Tesla and (depending on the performance of its stock) the world’s richest person, made a deal to purchase Twitter and take the social media platform private. His politics appear to be the standard politics of the tech industry ownership class—as indicated by his very public dissatisfaction with Twitter’s content moderation practices, his history of hostility to unions and worker safety, and his vindictive treatment of critics. This—along with his particularly public and online kind of bumptiousness—indicates to conservatives that he’s an ally and to liberals and leftists that he’s a threat. Some Twitter users fear a return to the unrestrained harassment and widespread neo-Nazi presence that characterized the site in the middle of the last decade. Others look forward to looser policies on banning and disinformation.

I’m a heavy Twitter user who does not wish to see a return to the days when blocking random hate accounts was a regular necessity even for low-profile accounts like mine. But I have no idea what mix of personal, pecuniary, or political motivations spurred Musk to take on this role. I can’t guess how he will balance the need to keep a liberal-leaning user base from walking away in disgust with the priorities of his lenders and his own enthusiasm for unrestrained discourse. If the big change to Twitter is that it ends being up a bit more oriented toward selling more electric cars and solar panels, that wouldn’t be the worst outcome.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

But there is more at stake in an event like this than the question of which team in America’s increasingly mind-numbing culture wars feels like Twitter is on its side. It also highlights the inherent fragility of building our lives online—an important reminder for, among other people, Christians who have been talking optimistically about a digital future for worship and community.

After the COVID-19 pandemic forced many churches to move fully or at least partially online, some writers and practitioners began to theologize this change as being not just an accommodation to an emergency but a good and perhaps necessary development in Christian practice. Our pre-2020 boilerplate celebration of bodies, embodiment, and presence—and yes, it was boilerplate, even when I was doing it myself—was overridden, first by the discourse of health and safety and then, at times, by optimism about virtual gatherings as the inevitable and necessary future form of church. When Anglican Church in North America priest Tish Warren, writing in the New York Times, urged churches to close down their worship livestreams in favor of the in-person experience, she was castigated as a stodgy Luddite who failed to take into account the needs of people with disabilities or chronic illnesses. At least that’s what people were saying on Twitter.

In my congregation, Facebook, Zoom, and YouTube have featured more prominently in our pandemic practices than Twitter has (though I have participated in compline on Twitter and have seen plenty of praying and liturgy organizing happening there). But whichever platform we are using for our ministry, it’s easy to forget that these are not simply utilities that allow greater access for more people. The user experience may be frictionless (at least for those with the hardware and internet access needed), and the service may be freely provided, but doing church on one or more of these sites is not like standing in the public square. It’s not like renting a facility. It’s not even like consuming a normal product. It’s more like putting ourselves under a form of sovereignty.

This is most obvious when questions about content rules are being debated, which sorts of speech and usage can trigger a suspension or a ban. But it goes well beyond this, into the algorithmic workings of the platforms, their relationships with governments, and their use of user data. Mark Zuckerberg’s fascination with Augustus Caesar suggests the particularly grandiose ambitions the Facebook founder has for his online empire, but he’s hardly alone in leveraging the scale and influence of his enterprise to act as a quasi government. Amazon’s vast scale has allowed it to turn state and local governments, to say nothing of retailers, into supplicants. Musk himself is planning to turn the tiny hamlet of Boca Chica, Texas, into his own city: Starbase.

There’s nothing new about oligarchs developing a taste for vast (and sometimes delusional) ambitions, bullying governments, or buying up media properties to extend their influence. But reading William Randolph Hearst’s newspapers is a qualitatively different matter from spending part of your day—or a significant part of your church’s ministry—subject to his personal authority. Wading through a paper’s scaremongering journalism to find the baseball scores is one thing. Unknowingly participating in a social media platform’s exposure of Saudi dissidents is another.

The counterweights to this kind of corporate sovereignty—unionized workforces, government regulation, even true shareholder oversight—are few and weak in this industry. Google and Meta are publicly traded but under an ownership structure that keeps all decision making in a few legacy hands. Musk plans to take Twitter private altogether.

So even as digital platforms promise to abolish distance and bring people together, regardless of mobility or vulnerability to infection, it’s critical to ask whether we want to make participation in their systems a central, even essential, aspect of church life. Our buildings, for all the limitations they impose and the compromises with the world they represent, are at least ours. When we’re in them, we don’t need to collect any data, add to anyone’s market share, live under any magnate’s rules, or accept any institutional compromises or cowardice but our own. It’s a hard kind of freedom. But however we feel about any particular online empire builder, we may well miss that freedom when it’s gone.