Neutrality or solidarity?

In Ukraine, faith-based humanitarian workers face a fundamental question about the nature of their work.

In February 2022, as missiles fell on Ukrainian cities and Russian snipers stalked the Kyiv suburbs, major international aid organizations suspended operations and ordered their staff to leave. The initial humanitarian response fell to Ukrainian civilians. According to Humanitarian Outcomes, a London-based think tank, “for the first six weeks post-invasion, virtually all humanitarian aid inside Ukraine was organised and implemented by local actors.” Everyday Ukrainians, who were themselves mourning losses in their own families and communities, still found ways to save neighbors’ lives.

While this instance of locally organized aid was necessitated by the particular conditions of this war, it is also part of a broader movement. Calls to localize aid have made their way into the humanitarian lexicon from the development sector, where localization refers to the belief that people on the ground should have more of a say in their own development. For humanitarian workers, especially those who operate in conflict zones, localization means that emergency money and the authority over how to spend it should be given to people from the communities affected by violence.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In April 2023, I observed these efforts on the ground with NGOs in Ukraine’s Transcarpathia region. I entered Ukraine from Hungary, traveling out of Budapest with a bus company recommended by a journalist friend. The unmarked black minivan was full—seven young Ukrainians and me, the lone American—by the time we reached the border. The sun had set. Our headlights lit up a guard who was waving us down; he approached the driver’s side window as we rolled to a stop.

“Are you all Ukrainians?” he asked, peering into the back.

Our driver answered truthfully, “No.”

“So hand over the Russians,” he demanded.

Some conversation followed, and I noticed the border agent’s smile as the other passengers laughed. The woman seated beside me explained: no Russian would enter the country through an official checkpoint. The guard stepped back, still laughing, and waved us on to the passport control kiosk.

My destination was Uzhhorod, the largest city in Transcarpathia and the headquarters of Dorcas’s Ukraine operation. Dorcas is a global development NGO founded by Dutch Protestant missionaries, now operating on three continents. For several decades the Ukraine branch ran small-scale development projects. Based in Surte, a village of 1,000 mostly Hungarian residents, Dorcas’s development work was attuned to this region’s distinctive history and character.

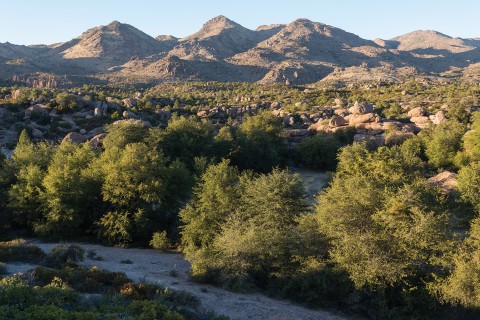

This area in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains has a diverse population: both Ukrainian-speaking and Russian-speaking Ukrainians, ethnic Hungarians, and Roma. Transcarpathia’s churches also come in a wide variety of styles, glittering and monumental but also intimately familiar. In Uzhhorod, one Orthodox church’s gold dome looms high above a four-lane roundabout; I also passed by modernist worship campuses for Baptists and Adventists. Outside the city there are unpaved villages with whitewashed Reformed chapels.

The first morning I was met in Uzhhorod by Ferenc Katko. The Dorcas Ukraine director, short and trim with jolly cheeks, was leaning against the door of his sedan. When I approached, he stepped away to reveal Dorcas’s blue logo on the door: a flower shape for “flourishing people and communities,” according to the organization’s PR.

As we pulled into traffic, Katko explained that Dorcas Ukraine had two offices, both focused on economic development: the original Transcarpathia team and a newer site in Zaporizhia. The offices had been independent of each other, but when the war broke out Dorcas transferred its Zaporizhia employees here under Katko’s supervision. Katko then hired additional workers to organize humanitarian relief.

“We’ve hired people from Kherson, Kharkiv, Zaporizhia,” Katko told me, naming regions in eastern and southern Ukraine. As we jerked our way through Uzhhorod’s streets, he said that 150,000 Ukrainians have moved to Transcarpathia—a third of the region’s prewar population. No one knows the precise numbers, he said, but Uzhhorod and Mukachevo, Transcarpathia’s two main cities, have likely doubled in size.

Safety is the simple wartime reason many choose to settle here. Throughout the country, Russian military ordinance has murdered civilians. Only once, however, in May 2022, did the Russians strike Transcarpathia, and that was a rural power substation. People make the journey to urban Transcarpathia for the normalcy of sidewalk cafes, sakuras blooming in city parks, even traffic jams.

Ten minutes outside Uzhhorod, we reached Surte. Katko slowed in sight of the Reformed church’s belfry. We parked around back and stepped out onto a crooked path heading toward a squat wooden building.

Katko announced, “This is Dorcas.”

I found it odd that Dorcas would coordinate its entire Ukraine operation—40 staff, ten partner organizations, a multimillion-dollar budget—out of an ethnic minority village in the country’s most remote province. As Katko held open the front door, I asked if it was a problem to be so far from Kyiv’s political power brokers.

He explained that the Transcarpathia location was a legacy of Dorcas’s missionary founders, the Dutch Reformed who had brought the organization to Ukraine. A denominational affinity had drawn them to this community where the tallest building is the Hungarian Reformed church in the town center.

Katko introduced me to his staff, popping his head into six office suites one by one. I said “Dobryi den” to the Ukrainians and “Jó napot” to the Hungarians. Staff members told me about the organization’s ongoing preinvasion economic development work: building a social safety net for village elders, teaching farmers entrepreneurship, helping Roma families break the cycle of poverty.

The war hasn’t only changed the staff’s makeup. It has also shifted the organization’s original faith orientation. “We give food and cash grants,” Katko said, “but leave it to our partners to serve people’s spiritual needs. This was important to us for a long time, but since the outbreak of the war, church programs aren’t our main activity.”

For my second day, Katko said he wanted to spotlight Dorcas’s mental health program. Dorcas’s program is run for Ukrainians by Ukrainian therapists, who have specifically tailored their programs and materials.

My next morning began at the table of an Uzhhorod café, sharing espressos with Dorcas’s team of energetic clinical psychotherapists. Combined they share 50 years of clinical experience, working with both children and adults. Olena and Natalia are both from Kharkiv, where they met when Olena sought treatment for her granddaughter. Yana, the youngest therapist, was in Dnipro, running a social inclusion program for children with Down syndrome.

Natalia and Olena had lived under Russian occupation. When the war broke out, Yana had taken in her mother, who fled from the city of Berdiansk, which today remains under Russian control. Eventually the family moved to Transcarpathia for this opportunity with Dorcas.

Natalia was the most recent arrival. She had stayed in Kharkiv after the invasion to work with a humanitarian start-up, one of the ad hoc operations that emerged after international groups left Ukraine. They collected donations of flour and salt, she said, and brought the ingredients to restaurant staff now using their kitchens to bake bread. They delivered the loaves to soldiers and the elderly, even to people who had fled the shelling into the city’s subway tunnels.

When the front line retreated, Natalia also led convoys into and out of Russian-occupied territory: “We tried to help people get out, to escape. We drove into the town of Kupiansk, which was on the front lines, and put people in our cars.”

Once, when Russian soldiers blocked a road, Natalia got out and guided people through the fields to safety.

In June 2022, a missile barrage struck one of Natalia’s aid caravans. She suffered a concussion. Olena, who was in Uzhhorod by then, mentioned the mental health and psychological support program to Natalia, who liked the idea of helping others while recovering in Transcarpathia.

That morning we spoke about the struggles of parents who’ve been displaced. Mothers and fathers have difficulty finding jobs in cities where they have few connections. Even when they find work, childcare is a struggle; kindergartens and preschools in Uzhhorod are overcrowded. The lack of childcare has profound psychological effects.

“Moms who aren’t working feel like they’re on permanent maternity leave,” Yana said, “but when they work, they’re able to express themselves. They’re able to socialize in the community, too.”

This seemed to be true of these therapists, as well. As they spoke about the experience of others, they also spoke about their own experience of coming to a new community, feeling isolated, and finding connection through meaningful work.

Yana showed me their workbooks, the materials Dorcas had designed specifically for displaced Ukrainian children. One page depicts two women sitting at a table. The therapist asks, “Are the women friends?” As the child responds, Yana explained, they might remember old habits of social interaction and rediscover that their surroundings are not threatening but supportive.

I asked what language they use when talking with the children, Ukrainian or Russian?

“The children speak both Russian and Ukrainian,” Olena answered, “but we try not to get into conflicts with the children when they speak Russian.”

They do not force children to speak Ukrainian, the therapists explained. They’ve had plenty of therapeutic conversations with children who speak in Russian while they reply in Ukrainian.

“We always speak in Ukrainian,” Olena said, “even when they answer us in Russian, because now they need to know Ukrainian.”

While the international community is not used to thinking of psychotherapy as a political tool, it has long been a state-funded profession in parts of Europe. In the former countries of the Soviet Union, psychotherapy is political, if only because therapy is always talk therapy, and talk is always talk of the nation-state.

In Ukraine, helping professionals like psychiatrists have long been state employees. They help people heal, but in the process of administering psychotherapy’s talking cure, they have also helped the government make sure that citizens of the nation-state speak a single national language, which until the end of the Soviet era was Russian.

The widespread use of humanitarian trauma therapy in Ukraine has put humanitarian workers, traditionally bound by the international community’s norms of neutrality, in a new and awkward position. It has forced their hand in the debate between those who believe humanitarian organizations should stay neutral and others who use aid to take a stand in solidarity with victims and the oppressed.

Before the war, Russian-speaking Ukrainians observed a public-private divide between the two languages. Russian over breakfast, then Ukrainian in the classroom or with one’s boss. But anti-Russian sentiment has grown tremendously since the invasion. Which language you speak now shows where your allegiances lie in this conflict between an invading nation and another defending its right to exist. Many bilingual Ukrainians now speak only Ukrainian whenever they can.

How should aid workers, especially those working in the area of trauma therapy, handle the divisive question of language?

I posed this question to Leila Verkerk. Verkerk is a PhD researcher in linguistics and leads a project at the University of Groningen, in the Netherlands, about how multilingual psychotherapy patients express trauma. Verkerk’s research includes bilingual Ukrainians who learned both Russian and Ukrainian, but in sequence: that is, they spoke Russian as infants at the kitchen table, for example, and later on Ukrainian from behind a school desk.

Verkerk’s interest in language and emotion is both personal and professional. She was born Leila Nazrulaieva, to an Azeri father and Russian mother, in Baku, Azerbaijan. The family moved to Ukraine when she was four months old, and today she considers herself Ukrainian. She is herself sequentially bilingual. With her two older brothers, she learned Russian at home until she started school. While she married a Dutch spouse and moved to the Netherlands to study, her parents and brothers stayed in Ukraine, and they continue to speak both languages every day.

During our conversation, Verkerk maintained her thoughtful and genial composure as we chatted and swapped stories about our toddler children. But she turned to look out the window, and I heard her voice shake, when she began to tell me about her brothers’ experiences during the invasion, including during one of the war’s darkest moments. In Irpin, a Kyiv suburb where her brothers live, UN investigators have uncovered a mass grave with more than a thousand bodies, which they cite as evidence of Russian war crimes.

For months the front line was a mere two blocks from her brothers’ apartment. “There was daily shelling, daily bombing, daily shooting,” Verkerk told me, “but they refused to leave.” After the Russian forces retreated, her brothers helped bury the victims.

They refuse to tell her anything more.

“You shouldn’t know what happened here,” Verkerk recalled her brother saying. “I’ve seen a lot in my life, but this kind of brutality? Never.”

For her research, Verkerk has interviewed more than 60 multingual people, patients as well as psychotherapists. She said the Dorcas therapists’ practice is atypical.

“Therapists usually follow their client's language choice, as long as their proficiency allows,” Verkerk told me. “It’s strange for me to hear that therapists would keep speaking Ukrainian despite their client's clear preference for Russian.”

Clinical research findings, Verkerk told me, suggest a link between using a primary language and access to deep emotions. Using a primary language in therapy may help clients come to terms more quickly with traumatic experiences, improve their anxiety management skills, develop new and meaningful relationships, and stabilize these strategies and relationships to ensure long-lasting positive outcomes.

Children who speak Russian with family may prefer that language to tell a therapist about a conversation with a parent or other loved one. These Russian-language memories can help express the child’s worries about a parent now absent at the front or even their grief if they have lost a loved one. Dorcas’s therapists were clear, though: they do not force children to speak Ukrainian. However, Russian-speaking children, faced with a counselor who replies in Ukrainian, may yet feel subtly obliged, which may have a negative effect on clinical outcomes, according to Verkerk.

On the other hand, some teenagers—even Russian speakers—have begun using the language to reclaim their Ukrainian identity. And they might prefer Ukrainian not only in therapy but also in everyday life, where speaking Ukrainian is increasingly seen as an act of patriotic resistance. Verkerk speculated that Dorcas’s therapists may be leading these older children toward the language as a positive social resource, a way to express their allegiance in a country at war.

Katko praised his Russian-speaking employees at Dorcas for mostly speaking Ukrainian around the office. He said he understood why they made this choice and why his friends frown nowadays when they hear Russian in public.

“They say that Russia is the aggressor,” he explained, “and that no one should ever speak the aggressor’s language.”

He scoffed at one of Putin’s justifications for the invasion: preventing Russian-speakers from being persecuted. “This war isn’t about saving Russian-speaking people,” said Katko. “The Russians are destroying everything. They’re killing everyone. This is a blood-soaked war.”

But he rebuffed me when I asked if anti-Russian sentiment was affecting Dorcas’s work. He said that wartime politics had not affected the decisions they made about distributing aid: “We figure out who is in need, who needs help, and we help them. We help everyone, whether they are Hungarian, Roma, or Russian-speaking Ukrainians.”

This sounded like Katko was simply repeating company policy: like most humanitarian organizations in war zones, Dorcas is neutral. But he also said that his personal example helped as much as any regulation.

Katko learned Russian from his father, who’d picked it up in the Soviet army. He learned Ukrainian in school. And he’s part of Transcarpathia’s Hungarian minority. Because he speaks all three languages and comes from a minority culture, he said that he answers people in whatever language they address him.

Other ethnic Hungarians in Transcarpathia, including some humanitarian workers, said they felt uncertain about the implications of Ukrainians’ growing national pride. For the second half of my trip I stayed with József Sipos, a Reformed pastor and director of an NGO called Supporting the “Forgotten” Children of Transcarpathia (KEGYES). Sipos has a village parsonage in Perekhrestya—population 927, most of them Hungarian. During my four days there, I met two of his four daughters and many of his parishioners, and I saw him preach in the village’s one-room stone chapel.

Sipos founded KEGYES in 2017 to carry out medical development work, raising money to renovate a section of Mukachevo’s children’s hospital.

The pandemic then prepared Sipos to make the wartime pivot, shifting from development to humanitarian aid. After pandemic-related restrictions closed hospitals to visitors, KEGYES began distributing food parcels to the impoverished families of hospitalized children. When the fighting broke out, he rebranded the parcels “SOS packages” and reached out to donors in Hungary to expand the program. KEGYES has distributed thousands of SOS packages to people arriving from conflict zones in eastern and southern Ukraine.

I was attracted to Sipos’s deep faith but also to how lightheartedly he bore it. “Who knows if anyone will show up,” he remarked with a laugh before a weeknight worship service.

But thinking about the village’s future made Sipos serious, even fearful. While he was showing me around his neighborhood, he mentioned that there was no available housing in Uzhhorod or Mukachevo. Rumor had it the government was going to house displaced Ukrainians in Perekhrestya.

He pointed to a large concrete office building crumbling in front of an overgrown park. “It was the office of the old Soviet collective farm,” Sipos said. “Now they’re talking about renovating it for housing. There are 800 Hungarians here. If you add 100 Ukrainians, what will that do to the village?”

If I wanted to project nationalist intentions onto the Ukrainian government, I could think housing refugees in Hungarian villages was a backdoor effort at ethnic assimilation. Alternatively, I could say that the government was trying to do good by desperate people, and that if Sipos’s village lost some of its Hungarian character as a result, it would be an unintended consequence.

Hungary’s government, across the border in Budapest, takes the former view. Since the war began, it has repeatedly voted against Ukraine’s applications to join the European Union, because Ukrainian law requires that children speak Ukrainian in school. Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán says the policy forces Transcarpathia’s Hungarians to learn Ukrainian, with assimilation being the endgame: turning Hungarians into Ukrainians. While Orbán complains about Ukraine disregarding European values like ethnic minority cultural self-determination, his own coziness with Putin should color any evaluation of his criticism: a Europe that doubts Ukraine’s moral standing might play into Putin’s hands by drawing down military support.

Sipos led me up to the collective building. I squatted at a basement window, but I couldn’t see through the pane of dusty glass. In our silence, I wondered how much Sipos would admit to being under the influence of Hungary’s fear-stoking politicians.

“Are you afraid of this?” I asked, standing again to face him.

“Of course not!” he bridled at the question. “If they’re Protestants,” he added, “they might come to church. It would be a mission opportunity.”

My time with Sipos underscored the moral conflicts that Ukraine’s humanitarian workers face today. The war in Ukraine has put a spotlight on an ongoing debate over whether humanitarian professionals should stand in solidarity with oppressed Ukrainians or remain neutral in the conflict. In May, the International Committee of the Red Cross’s president declared that “the world needs neutrals” in a New York Times op-ed. Mirjana Spoljaric wrote that neutrality is an essential element of the system of international humanitarian law, rebutting calls for organizations like hers to take sides in favor of Ukrainian victims.

As I met and talked with humanitarian workers in Ukraine, I was also observing in real time how the move to localize humanitarian decision-making is changing this moral debate over neutrality. Yes, localization means shifting money to Ukraine and out of Spoljaric’s Red Cross headquarters in Switzerland, internationalism’s historic metropole. But it also means shifting the responsibility to make moral decisions. Ukrainian aid workers are grappling with some of the most difficult moral dilemmas humanitarianism has to offer. The country’s mix of cultures and languages brings this to the fore as perhaps no other conflict to date.

On the one hand, a growing number of humanitarian organizations acknowledge that children have the right to culturally and linguistically competent medical care. This right seems to conflict with Dorcas therapists’ desire to honor Ukrainian national culture. The international humanitarian sector also acknowledges the power imbalance at work in relations between children and adults. Does a child’s desire to conduct therapy in Russian deserve special deference, given the inequalities built into interactions between minors and adult therapists?

Whether or not the international sector wants to recognize it, the debate between neutrality and solidarity now lies squarely in the hands of Ukrainian humanitarian workers. Which is to say, in the hands of the people who are being directly and personally affected by the violence engulfing their country.

Localization should also be a call to accompany humanitarian workers’ ongoing efforts to satisfy the competing demands of neutrality and solidarity. As the debate over neutrality and solidarity proceeds, and whatever policy takes hold across the humanitarian sector as a result, it will only enjoy true and widespread legitimacy if it reflects the compromises that these individuals—who are aid recipients—are working out for themselves.