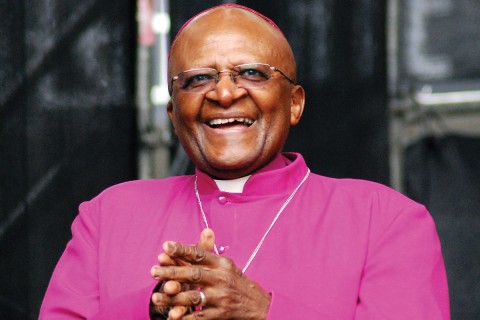

Desmond Tutu’s transformative vision

He thrived on the process of endearing himself to all who hope for better days.

Black people raised in apartheid South Africa hitched their survival to some degree of accommodation to White ways. The elite few who became “pioneers” by serving as the first Black person in a given role were surrounded by White colleagues and learned even more about negotiating Whiteness. By age 44, Desmond Mpilo Tutu had already held a few such roles and had spent eight years living in England. He nurtured a growing network of international contacts with the customary ritual of an annual Christmas letter. By his ninth pioneering role 11 years later—as Archbishop of Cape Town—he was an expert in navigating White supremacy.

But that’s not the only reason North Americans grew to love him so. It was also because he loved us, too.

Tutu, who died last month (see obituary, p. 21), thrived on the process of endearing himself to all who hope for better days: the oppressed, certainly, but the overprivileged as well, if for different reasons. He even tried to charm those who were most opposed to the changes he passionately longed for. Within South Africa’s socially conservative churches, Tutu’s leadership effectively eroded gender and LGBTQ discrimination earlier than anywhere else on the African continent and many places beyond it. All this while championing the antiapartheid campaign for which he became best known.