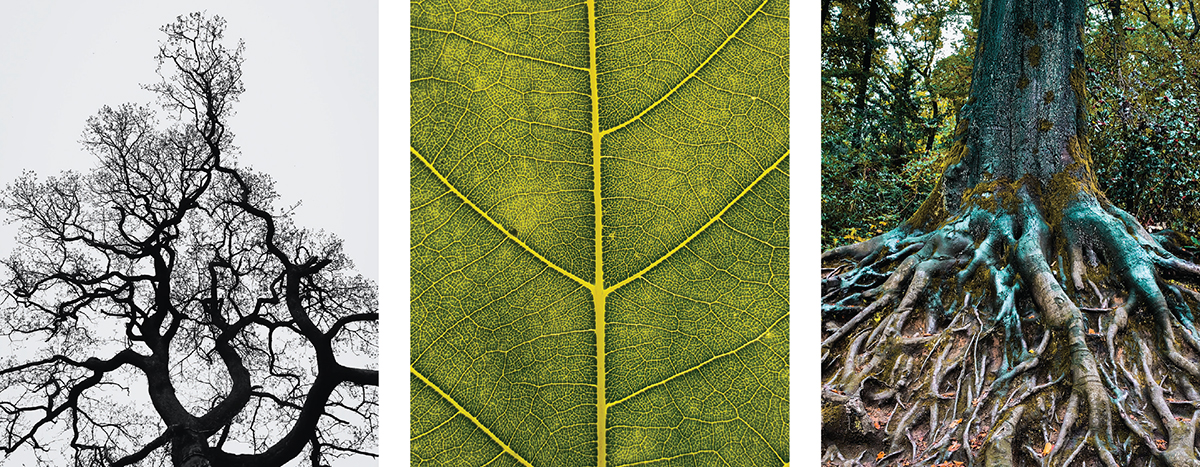

Systematic: an organized set of doctrines, ideas, or principles usually intended to explain the arrangement or working of a systemic whole.

SEVERAL TIMES A YEAR I welcome students into a classroom where they are introduced to theology. They are supposed to learn the history of Christian doctrines, understand their interrelationships, and begin to recognize the theologies that shape them even as they encounter the theologies of others.

A systematic theology might begin with a prolegomenon (such a big word to describe an introduction) on how we are framing the problem, followed by a doctrine of God, then creation, then sin, then the incarnation—all building a story that helps to explain what’s come before and to help us make sense of today.

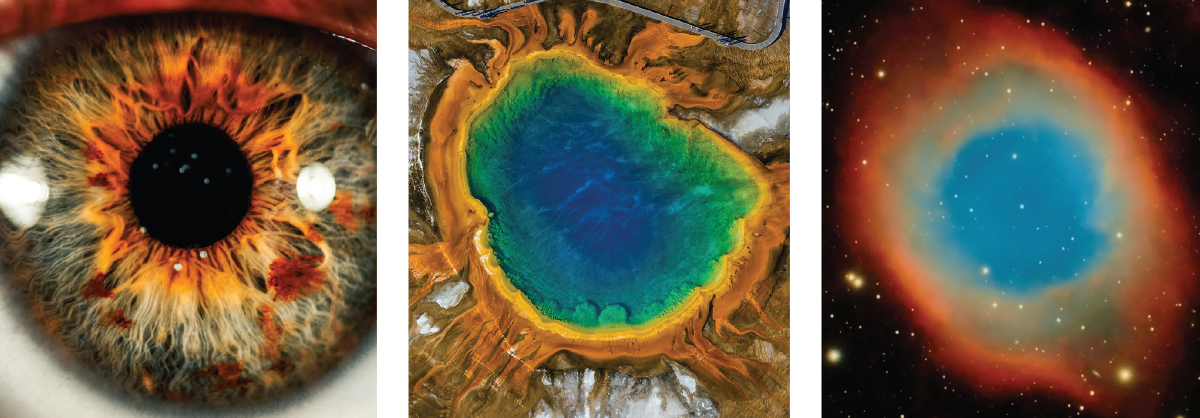

We’re walking through the park, and my five-year-old asks me, “Where is God?” I’m not sure what sparks his question. A leaf falling from its branch, the chimes woken by the wind, the cat that curls its back up and stares at us as we pass. “Where is God?” he asks again.

My students come from so many places. Some are looking for theology to confirm what they have already been taught. They want to know the foundation and the joints so they can shore up their own home. Some come with fear because Christian doctrines have never been anything but violence for them, carefully erected walls meant to scrape off everything of who they are so that they can press inside through the gaps.

Some simply don’t care. Why do doctrines even matter? Why all this philosophizing and arguing over things we cannot know? It’s all about how we live, right? Or maybe it doesn’t matter because faith doesn’t matter, the church doesn’t matter, maybe even God is little more than an idea used to justify how we want to live or how we want to determine how others should live.

And some of them want it to matter. They want it so desperately that they left the church long ago because they saw God alive in so many other places instead.

I take his face in my hands and tell him to look at me. “God is in my face, and God is in your face. Look at your hands. God is in your hands. Look at the stick you’ve been carrying. God is in that stick.”

“God is a stick? God is you? God is me?” he asks.

“Well, no,” I say. “God is not you and me and the tree exactly.” I am beginning to dig a hole for myself. “God is in all those things because God holds all those things together,” I try to explain.

He does not look convinced.

A good teacher is a luminous creature. Wherever he goes darkness disappears. He even carries candles in his pockets, which he lights whenever he finds a dark corner of his text. . . . I became sure that I was no longer a good teacher when, instead of turning the lights on, I preferred to turn them off.

—Rubem Alves

We bend down over a patch of dirt, and I scoop up a little soil that isn’t hiding under the field of dandelions and say, “The dirt is us. The hands are God.”

I squeeze and press till the oils and sweat of my palms mix in with the dirt, and then I spit on it a bit just for good measure, which makes my little boy laugh and laugh. That little pile of dirt becomes a ball. I keep squeezing and rolling it in my hand to keep it damp.

“I am in this ball because part of me is in it, but the dirt isn’t the same thing as me. I’m not the same as the dirt. But it has part of me. It stays a ball because I keep giving it something of myself. I keep giving parts of myself because I want it to be. I want it to be because I love it.”

He holds his hand out to me. “Can I be God now?” he asks.

And now I understand the metamorphosis I underwent: I no longer deal with words as things to be used. I deal with them as things to be enjoyed. I am no longer a teacher.

—Alves

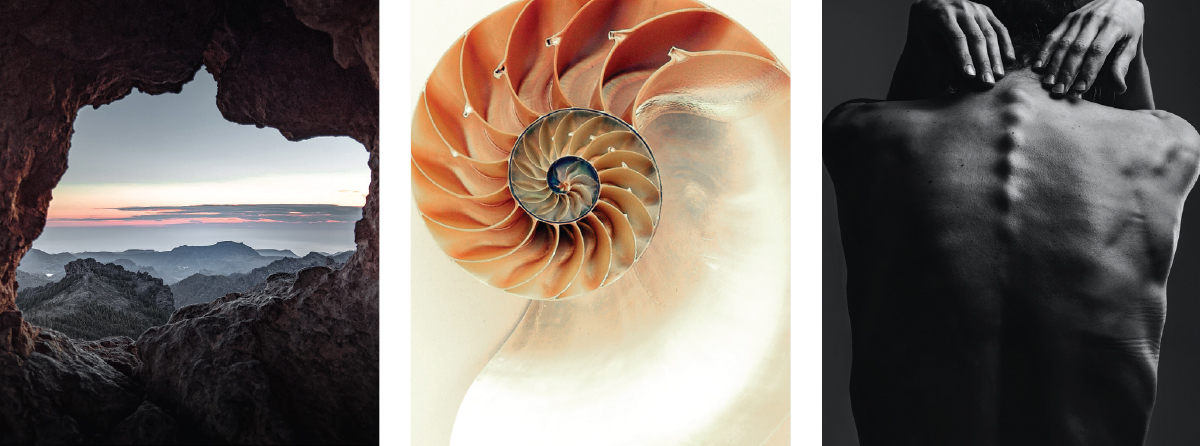

Theology is the bridge over the gorge, the tunnel under the mountain. It is the stories and descriptions that help us grasp a truth of what is happening, of who God might be, of who we might be when the stories seem to go silent or contradictory. Or when those who wrote simply could not have fathomed the world we occupy, with all of its possibilities and its dangers.

He holds his hand out to me. “Can I be God now?” he asks.

I know this doesn’t answer the questions of transcendence and immanence and the nature of God. But sometimes I think about all my ramblings about transcendence and immanence and what God cannot be which helps us to see what God must be . . . and I wonder whether all the words I’ve read and written get me any closer to the wonder of one who is with me but isn’t me. Maybe we don’t need more words that say everything. Maybe we just need a few that help us to describe what it’s like to play in the dirt.

God plays the part of kin, a member of the community. . . . As many women often feel themselves in bondage or lost in the “foreign lands” of affinal communities, the theologians see the acts of God in the Hebrew culture portrayed in the Book of Ruth as illustrative of the kinship role of God.

—Mercy Oduyoye

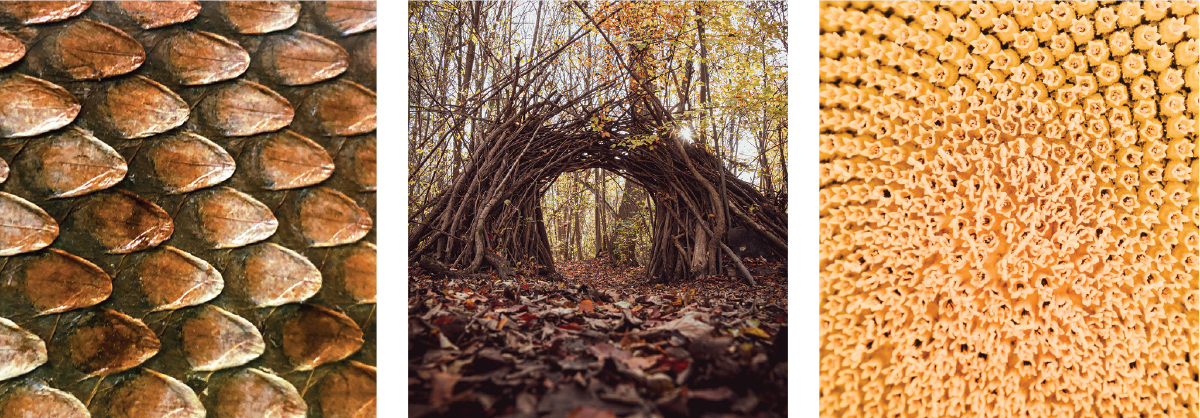

ONE OF THE REASONS I came to love theology was its ability to help me make sense of the world. The idea of systematic theology, especially, helped me to see how so many disparate parts fit together. How we speak of God and how that shapes our understanding of who God is, which then shapes what we believe creation is and human beings within creation, to the Fall of humanity, to Jesus, to salvation, to the consummation of all things—more than doctrines or a system of beliefs, these all hang together in an intricate and beautiful story that lives in us and our shared existence.

This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh.

—Genesis 2:23

I woke today, and the first thing I saw was clay like me. Well, almost like me. Some curves in different places and some strange dangling bits. It is red-brown and rich. The clay is lighter than me, lighter than my . . . skin? Fur? It is dark and smooth like the soil where the sweetest fruits come from.

This skin-and-clay creature tries to name me. “Woman,” it says. The name sounds strange to me, but I’m not sure what else I would call myself so I just keep looking and breathing, taking in this world I find myself in. Maybe I will choose a new name after I’ve let my toes sink into the stream that white trees bend over.

Creation, we are taught, is not an act that happened once upon a time, once and for ever. The act of bringing the world into existence is a continuous process.

—Abraham Heschel

We are some of the animals here. We all eat. We run. We nuzzle noses and help to clean each other. We are still giving names to all these other animals we meet. I don’t know what they call each other. I guess the names are more for us than them.

But the clay I woke with, our fingers fit. When I look up at the tree, they seem to want to help me reach the sweet, orange globes that hang. And I want to help them. Some of the other animals will come and go. But the clay seems to follow me, and I like to follow them. We seem to know each other’s sounds, and it feels safer when they are around.

There is something that hangs in the air when they see me, when I see them. I think it’s true for all of us earthen things. We don’t have a word for it yet, what hangs in the air between us all, above us, in us, but we know it’s there. We cling together and walk together and wander and hold each other when we are afraid. I hope we will be less afraid tomorrow when we wake again.

IN THESE STORIES we tell about ourselves, there could be so many moments of waking, of feeling the world around us and asking, “Who is this one I am with?” And I guess in every story there is something that falls, some tension that breaks the peace, that etches in some outline of what we thought our lives were supposed to be like.

We tell the stories like this because there’s death here, too. And not just the beautiful death of a tree that has lived its life full and spread its branches wide and given shade and homes only to fall and become mulch. There isn’t just the suffering of muscles strained and sore as you crest the mountain path and see the valley below and tell yourself, “I came from there.” No, there is suffering that comes from the screaming and shouting at all that is, or the fear of losing, or the wanting, or the . . . there is never just one fall.

My eyes were open.

The finches circled, and squirrels scrabbled around trees.

They seemed only concerned about food or each other.

Were they so different? These little things ran as we walked

through the trees, or they puffed and snarled the same way each

day, as though we had not just passed by that way yesterday.

I do not puff out my chest or run when I’m scared.

I do not curl my back like a cat or snarl like a dog.

No, we are not the same.

We are different

We are not so weak.

I must be more than that.

We are more than that black horse that runs

in the fields beyond the stream or the cow that

does nothing but graze after we milk it in the

morning.

Yes, I feel hunger gnarl my insides when the

berries have withered but the salmon haven’t begun to swarm the river.

Yes, I look at her and imagine my hands running

up her thigh and my mouth on the bend

of her neck.

But I am not like those creatures who mount

each other mindlessly?!

The world is not a safe place to live in. We shiver in separate cells in enclosed cities, shoulders hunched, barely keeping the panic below the surface of the skin, daily drinking shock along with our morning coffee, fearing the torches being set to our buildings, the attacks in the streets. Shutting down. Woman does not feel safe when her own culture, and white culture, are critical of her; when men of all races hunt her as prey.

—Gloria Anzaldúa

Look at that elephant with its loping heft

I am so small next to her.

Look at the wolf and her pack.

All I can do is hide if it catches my scent.

No! I am not prey.

I won’t be prey.

I am not like them.

I am no animal.

I am human.

I am not small.

I am not weak as I seem.

I am not as unknowing as I feel.

I am not as needy as strawberry bushes at the end

of summer,

as this one I wake with,

as that deer

I name. I am not named.

It’s clear that our stories foment violence and exclusion and silencing in order to give our communities shape. Notions of faithfulness and unfaithfulness are never just ideas; they are always bodies to be excluded or disciplined. As I walk with undergraduates in introductory theology courses, we struggle with how to make sense of this problem. And shouldn’t theology help us to become more loving people rather than more certain people?

Let me snap these branches and weave a basket.

I’ll wind these fibers into something

to cover my weakness, my desire, my waste.

See!

Even the trees serve me. Let me burn them to

make a field.

See!

I will not hunger again.

See!

How I lift these stumps, these

enormous rocks!

(Who cares if you gave birth to new life in groans

and sweat and then somehow nourished them from your own body.)

See!

I killed the creature that hunted us.

I fed us!

(Who cares if you gathered the wood and crushed the herbs and

turned the roots and bone into broth and the berries into glaze

and turned the meat over in the fire every ten minutes until it had

the feeling of warm fruit in our mouths.)

See!

I am not like you. I am not like this world.

See?

Systematic: an organized society or social structure regarded as stultifying or oppressive.

HOW COULD ALL THE PAIN and uncertainty in our world now be captured by an explanation? Some sort of rationalization for why the world is the way it is and why it feels like we are sometimes hurtling away from God rather than growing toward her? This is usually the question my students ask the most. Why?

But I don’t know. Not really. I have hope that this isn’t the end of everything. Not that there is a master plan or a grand design, but that the God whom I’ve felt and seen in my life and the lives of people I love lives and is bigger than evil’s raving gesticulations or calculated consumption.

How do I know? I don’t know, but there is the story of a woman who was tilted toward life in a world even more violent than mine, and she could say yes.

Why would you come to Mary if you were not going to receive anything from her? What did you see? What did you want to learn? To love? The way she held her mother or sang her sister to sleep? Or was it the way she shook when soldiers marched in her streets with spears heavy from the bloodied bellies of her people on their tips? Did you need to feel her hunger for your people and the pain of their toil filling other people’s baskets?

She walked through dusted streets, her life tilted only toward betrothal, marriage, and bearing heirs. For so long the coils of men’s words hemmed her in, slid her mother’s knowings into drawers to be used but not seen.

But you saw what she saw. As promise knit into muscle and bone, you said, “I want to be raised by you. I want you to teach me to pray. I want your life to be the life I follow with my eyes as the world becomes known to me. I want to hear the tremor of your voice when we walk among our neighbors who hunger and thirst. I want to know the world through your life, your humanity.”

I tell you, something greater than the temple is here.

—Matthew 12:6

How can this be? To see Word and love and woman knotted into Mary’s son?

She said yes. God kneaded clay into toes and fingers—eyes opening in the warmth of liquid life, beginning and end listening to garbled voices from within skin and bone. The push, push of a heart that said yes to harboring the holy.

She carried you so far, ushered you here and there as empires lashed and fought. Until one night a stall became a tabernacle of straw and stone. In walks the holy of holies, the priestess’s robes parted like a veil ushering in the presence of God. She nursed you, fed you who feeds us all.

Only-begotten, recognized in two natures, without confusion, without change, without division, without separation.

—Definition of Chalcedon

“I will be your God and you will be my people” rumbles from within Israel’s daughter—the swell of words to Abram and Sarai crashing upon humanity in Mary’s song and then her birthing groans.

Her body and breath tethered to the beginning of all, arriving in the press and release of muscle. Her arms and face and fingers tense as her body softens to life coming forth.

Her breath, her sweat, hope becoming flesh, Spirit and clay—she brings Word into presence. From the darkened den she emerges, light pouring from within, you, the Holy One, in your priestess’s arms.

And he came and preached peace to you who were far off and peace to those who were near.

—Ephesians 2:17

And who were you that emerged from the holy place? Wisdom? Mind? Word? Unknotting words of male above female, let the old pass away, the new has come in hungry cries of beginning and end and in the faith of our mother Mary.

You were Word without words, God swaddled in need, seeking her eyes, rooting for your mother’s life. Embraced by your father’s arms and warmth so you could sleep. As you slept you brought peace to us; in your need you fed ours.

You, God enfleshed, are never without us. We are never without you. Let us be like you; let us be like her.

Our theology class would reflect on the Gospels and read about how people understood who Jesus was and argued about his identity. We would each have different parts of the story we lifted up, places where we saw ourselves and our neighborhoods. And we would all put them in the pot and begin to ask what we needed freedom from: What are the chains? What does the kingdom of God’s arrival look like in your little corner of the world? We might ask how we could be a little more like Mary, how we might bear God’s life inside of us, how to say yes despite the empire’s no.

All human beings are the people of God. They belong to God’s household housed on this planet and around God in the unseen realms. All of creation is cared for by God, the source of our being. The whole cosmos constitutes the oikonomia of God. In God’s household religious people discern many hearth-holds. . . . The church is indeed a hearth-hold with God as mother, the whole earth is the hearth and all human beings as the children of God.

—Oduyoye

Systematic: a regularly interacting or interdependent group of items forming a unified whole; harmonious arrangement or pattern.

THIS IS THE PART OF THE ESSAY where I should offer an apologetic for systematic theology, for the church—the part where I say, “yes, but actually,” and then offer a new way of thinking about why systematic theology matters. But this isn’t that kind of essay, because the all-encompassing story of everything always leaves too much out.

I suspect the idea of theology as a story, as an art, as literary, as ambiguous pieces sewn together might feel frightening. Where is the tradition? Where is the historical framing? Where is scripture? Where are the counterarguments?

None of what I’ve said means we don’t need those things. But maybe we need more.

See, now, my soul,

How he who is God blessed above all things,

Is totally submerged

In the waters of suffering

From the sole of the foot to the top of the head.

In order that he might draw you out totally from these sufferings,

The waters have come up to his soul.

—Bonaventure

Maybe the whole idea of a savior is too neat. Maybe the idea of forgiveness and God abiding and living in our midst feels too much like an invention.

But then there’s that line from a song that speaks to your moment. There is the meal offered when you are hungriest, the small moments that add up to more than they should. Somehow there are so many little bits of your life that can’t make sense unless there’s something that isn’t you filling in the gaps, calling, prodding, holding.

Here the bread is not the kind of bread the baker bakes, nor is the wine the kind the vintner sells; for he does not give you God’s Word with it. But the minister binds God’s Word to the bread and the Word is bound to the bread and likewise to the wine, for it is said, The Word comes to the element, and it becomes a sacrament.

—Martin Luther

She steps out from the little closet behind the choir loft in black Jordan shorts and her blue soccer camp T-shirt. The stage has been cleared of the tall cross and the pulpit, and where there used to be a floor there is a deep tub and steps that have sandy grips, just like at her grandma’s house. She looks out on the congregation, her mother, her grandmother, her brother on his phone. The organ hums and the water in the tub shivers as the bass dances with the drums.

She takes her first step, and the wet warm climbs her toes to her ankles. She’s afraid she will slip, but warm hands grasp hers as she descends into the pool.

Not only do we turn to our relational bonds with each other, we must also turn to the God who shapes our hands, feet, necks, and dark, dark livers.

To be called beloved is to ponder these things in our hearts which we are to grow big.

—Emilie Townes

Standing there, waist-deep in water, “I do” and “I will” fall from her mouth, responding to the whispers of the midwife calling her forth.

“I baptize you in the name of . . . ” and she lets herself be pressed back, she lets herself fall, but her weight is not her own as the water crawls up her sides, up her back, her neck.

One last breath and then the water soaks through the strands of her black crown. Her eyes close. Wet and dark meet, and the new enfolds her.

[And God] said, “But I will be with you, and this shall be the sign for you, that I have sent you: when you have brought the people out of Egypt, you shall serve God on this mountain.” Then Moses said to God, “If I come to the people of Israel and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ what shall I say to them?” God said to Moses, “I am who I am.” And he said, “Say this to the people of Israel: ‘I am has sent me to you.’” God also said to Moses, “Say this to the people of Israel: ‘The Lord, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you.’ This is my name forever, and thus I am to be remembered throughout all generations.”

—Exodus 3:12–15

Water is everywhere. There is no place where it is not, where it does not cling to her, and in the dark the words dissolve into murmuring silence. Chaos. Peace. Muffled sounds.

Spirit.

Rise.

Welcome.

The pastor presses her hand into her back, and words rush in as the water rushes, her face pressing through the membrane into the world of air again.

The two women hold each other, and this newly born creature takes her first steps out of the womb, her clothes and hair heavy, stepping out into the world again, dripping with God and ready to share.