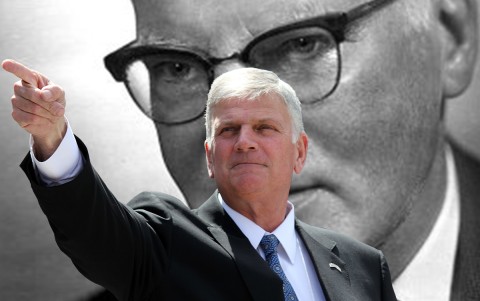

It’s 1933, and Franklin Graham is German theologian Paul Althaus

A limited but troubling historical analogy

German Protestant theologian Paul Althaus was a strong advocate for the existence of a “unique spiritual vitality” among the German people. As a young military chaplain during World War I, Althaus had become convinced of the special calling of the German Volk (people/nation). He saw the Treaty of Versailles as a deep national humiliation, and he had nothing but scorn for the Weimar Republic, the first democracy in Germany.

“Our Volk have had to endure the deepest questions of humanity more painfully and more profoundly than any other people,” Althaus wrote in 1927. “Our people have testified to God throughout history, in which God has entrusted it with something unique.” Althaus was construing Germans as an ethnically distinct group endowed with a divine mission. It is no surprise that he would soon embrace Hitler’s rise to power.

“Our country is facing trouble. Anger and despair have floated to the streets. We ask that you unite our hearts, to be one nation under God, for you are our only hope.” This might read like a quote from Althaus sometime after he endorsed Hitler’s election to the chancellorship in 1933. These are actually the words of Franklin Graham at the 2020 Republican National Convention.