Wrist-deep in the earth: Notes from the farm

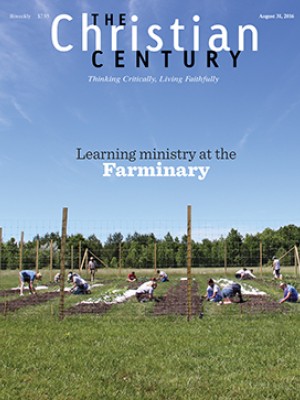

My legs ached, as well they should at the end of a marathon. In this case, it was the end of the spring planting and transplanting marathon.

There are actually a number of planting marathons each year on my brother Henry’s organic vegetable farm. The first takes place in the hoop house, where Henry starts tens of thousands of seeds of some 700 varieties. The next one takes place as he transplants the cool-weather starts (broccoli, cabbage, kale, brussels sprouts, fennel, all the alliums, and more) out of the hoop house and into the field. Around the same time, weather permitting, he direct-seeds the early-season crops—radish, spinach, cilantro, dill, and peas—in the field.

But the big planting and transplanting marathon comes when, during a short window, we must get all of the high-summer, late-summer, and autumn crops into the ground. Many of the seeds go into the planter hoppers behind the tractor, but others are planted by hand, seed by seed. We hand-seeded summer squashes, winter squashes, cucumbers, watermelons, muskmelons, sweet corn, popcorn, beans, and edamame. And with the tractor, we seeded new and succession plantings of beets, carrots, radish, arugula, lettuce, choi, mizuna, mustard, and turnip greens.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In addition to planting seeds, we put wave after wave of transplants into the truck bed and drove them from the hoop house down to the field. Getting things planted in the spring is always tricky. The soil needs to be dry enough for the tiller to work it up, but not bone-dry, or nothing will grow. And we need to plant when rain is forecast so that seeds will germinate and transplants will not wilt and die but take root and grow vigorously in their new home.

So Henry engages in a sort of pas de deux. The principal dancer is the weather, of course. She’s somewhat easier to follow these days, with radar at the ready, but thunderstorms pop up quickly and dissipate just as quickly. So when the weather’s right, we run the transplant marathon as fast as we can.

As we bounce down to the field on the back gate of the truck, we are filled with a mixture of excitement and trepidation. We hope for good weather leading to an abundant harvest but fear the many things out of our control: a wet year leads to diseases, a dry one to stunted plants, and just one minute of a severe hailstorm can shred an entire field of crops.

Still, we invest each seed and young plant with the exuberant yet completely rational hope of compounded returns. One small wrinkled kernel of sweet corn will yield a corn stalk with two ears of corn, each containing over 500 new kernels. One sweet potato slip will grow into a vine stretching six feet across the ground in every direction, yielding as many as ten large tubers in the fall. One tiny tomato start, in a good year, will yield 50 pounds of fruit.

This year the tomato starts are more gangly than tiny, since they have been waiting in the hoop house through a few rainy weeks, growing taller each day. We’ve had to modify our transplanting technique for these tall plants, burying their long stems on a horizontal slant so that only the top three or four inches are above ground. It may seem counterintuitive, but we bury the tomato starts to make them stronger and more productive. That way both the root end and the buried part of the stem will put out roots and pull up the nutrients and water the plant needs to grow and put forth many blossoms that will turn into luscious tomatoes.

The tomato transplant marathon starts with Henry tilling a fresh bed and his son, Kazami, walking behind with our homemade measuring stick, making marks every three feet all the way down the 200-foot bed. I follow him, placing a tomato start on each mark. Then I join the others, dropping to my knees in the velvety soil.

First, I lay the tomato start out horizontally to gauge how much needs to be buried, then scoop out a 12-inch-long trough that’s deep at one end and slants up to ground level at the other. I go wrist-deep into the pillowy earth with no effort and can imagine going in up to my elbows or even my shoulders. Who knows, perhaps I could go farther and wholly enter the embrace of the warm, dark earth.

Brushing that fantasy aside, I scoop out the trough and place the bottom of the transplant with its little block of soil at the far end, some eight inches deep. Then I carefully backfill under and over the stem, slanting it up at a shallow angle that ends at the mark Kazami made and leaves about four inches of green tomato plant above ground. I gently firm the dirt, taking care not to break the delicate stem. I finish by leaving a depression along the length of the stem to catch the rain we hope comes soon.

And so we continue, up one long row and down another: kneel, scoop, plant, firm up, scoot along to the next plant, kneel, scoop, plant, firm up, and scoot along again. Even as we imagine the fruits of our labors, those juicy Cherokee purple, red Brandywine, and Green Zebra tomatoes, our hopes are surrounded by uncertainties. Will it rain enough? Or too much? Will the season be too cold and damp for tomatoes and lead to fungal and bacterial diseases? Will the interns be able to persevere through the 100-degree days of weeding, mulching, trellising, and harvesting? Will Walnut Creek flood and wash the plants away? Will the fields be damaged by high winds or a freak hailstorm? Will the first frost come too soon?

Luckily, we are too busy to spend much time dwelling on the endless “what ifs.” There is precious little time to do anything but concentrate on the demands of the moment—and each moment is demanding, requiring speed, accuracy, and above all perseverance. After we finish the 1,000 or so tomato starts, we still need to plant 500 pepper starts and 500 Mediterranean and Asian eggplant starts. Then there are another 1,000 celery root transplants and about 500 basil plants. And we mustn’t forget the 800 sweet potato slips—plus the 200 that are still in the mail.

At this time of year we truly are, as Robert Frost wrote, “slaves to a springtime passion for the earth.” But there is more passion than slavery going on. Even the ache in my muscles and joints is tinged with euphoria. And it’s not simply the euphoria that comes at the end of a marathon. It is something deeper and comes from the sustained physical contact and communication between hands and knees and fertile earth.

The deep, black topsoil of my brother’s farm is soft, friable, and full of life. It covers not only my hands and knees but gets deep under my fingernails, and even into my nose and mouth. And all that mostly invisible life on and in me is enlivening. I have communed with countless species, and they have given me strength and a heightened sense of well-being. Perhaps this is the energy Aldo Leopold spoke of in A Sand County Almanac: “Land, then, is not merely soil; it is a fountain of energy flowing through a circuit of soils, plants, and animals.”

Or perhaps it is simply the euphoria of having done good work. And if all goes well, the work will yield even more goodness—with abundant harvests through the summer and into the fall, with enough frozen greens and storage roots to take us clear through to the following spring and the next round of planting marathons.