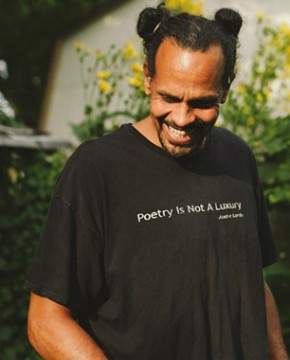

A garden of gratitude: Poet Ross Gay

"I've learned a lot from working with trees. More important, I've worked with people on imagining how to love each other."

Ross Gay teaches in the creative writing program at Indiana University and works with the Bloomington Community Orchard, a publicly owned orchard maintained by volunteers. The orchard’s harvest is available to everyone in the community. Gay’s books include Against Which (2006), Bringing the Shovel Down (2011), and Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude, which was nominated for a National Book Award in 2015.

Can you say something about the stories behind some of your poems, like “Ode to Buttoning and Unbuttoning My Shirt” or “Feet” or “Armpit”?

The “Buttoning” poem comes from the very real and mundane pleasure of buttoning a shirt. I was in the mind of Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet, who would say things like, “This is not something to take lightly.” As for “Armpit,” I was meditating on the beauty and sexiness of someone’s hairy armpit. The poem traveled to a place that wonders where desire originates and about the overlapping of desires.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

How did you know that these poems were adding up to a Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude?

I didn’t until I decided to call the book Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude. I did that before the book was done and before the poem with that title existed. I thought, “Oh, I want to write a catalog of unabashed gratitude, and I better write a poem called that too!”

What is unabashed gratitude? How is it different from abashed or perfunctory gratitude?

Unabashed is reckless and sloppy and unreserved and weeping and hollering. I suspect it knows that we are not with each other for very long, and so wants to vocalize it.

What role did your work in the Bloomington Community Orchard play in these poems?

That project is all over these poems. I’ve learned a lot from working with trees over these last years, and you can see some of that in the poems. More important, I’ve worked with people on imagining how to love each other. This book wonders about that.

What is going on in your garden right now?

Sadly, I’m away from it until August. There is about a year’s worth of garlic filling up three long beds, and various greens. Strawberries are happening, as are my beloved goumi, two bushes of the red gems sparkling in the sun. Nanking cherries. Potatoes. Herbs like crazy. Rugs of oregano. The plum and peach trees are loaded—pray the rot doesn’t waste ’em all. And I predict a good crop of figs this year.

You talk about poetry as “close looking, paying attention, going slow, a kind of training in receptivity.” Those phrases make me think of words like prayer and devotion. In “To the Fig Tree at 9th and Christian,” you write, “we are feeding each other / from a tree / at the corner of Christian and 9th / strangers maybe / never again,” and I think “communion.” How would you talk about the religious aspect of your poems?

I think you’re right to say something about communion and prayer. Coming together and making a livable common world is the most interesting thing in the world to me, and it’s interesting in part because it’s happening every second. I also have a lot of poems that explicitly appropriate biblical stories—or do revisions of them, or argue with them.

We so often think of poets laboring alone in solitary settings, but you’ve experimented widely with poetic collaboration.

I like giving away some authority or control in the process of making a thing. I like submitting and arguing. I search for surprise when making things “alone” (which I never actually do). Working with a teammate almost guarantees that surprise will happen. I like being on a team for the sake of witnessing collaboration.

You talk about joy as a discipline. What do you mean?

I mean it’s something that needs to be practiced, like foul shots, or grafting.