Stealing Jesus: A Protestant takes communion at mass

My ecclesiastical criminality has been going on for 45 years. It all started at a Trappist abbey in Virginia.

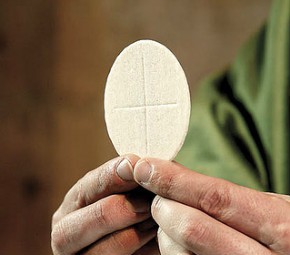

Last Monday I was stealing Jesus again, this time at Santa Maria de la Paz, near my home in Santa Fe. Occasionally I drop by for the 12:15 Eucharist. My ecclesiastical criminality has been going on for 45 years.

It all started at Holy Cross Abbey, a Trappist community nestled in the hills near Berryville, Virginia, about 70 miles from the nation’s capital. In December 1972, psychologically and spiritually exhausted from that fall’s elections, which were still shadowed by the Vietnam War, I drove anxiously to Berryville. Over the phone Father Stephen, the abbey’s guestmaster, had warmly welcomed my hesitant inquiry.

The next six days changed my life. A spiritual, mystical encounter revealed that I could rest in the reality of God’s love. The vigils beginning at 3:30 a.m., followed by silence anticipating the rising sun, culminated in a morning service of Eucharist where Christ’s flesh and blood became tangible, real, and irresistible.