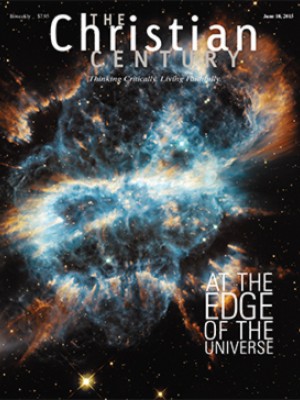

Stargazing

Years ago I lay on my back at the beach with a young son, looking up into a brilliant star-filled night sky. He broke the long silence by asking unbidden the ultimate ontological question: “Daddy, who made God?”

This issue contains two marvelously thoughtful and thought-provoking articles that approach my son’s question. Karl Giberson begins by observing that timelines of the history of the universe shown in freshman astronomy textbooks often begin with a question mark. Science has pushed all the way back to the Big Bang but not before it. In fact, there is a debate within the scientific community about whether the matter of ultimate causation is even a scientific question.

Giberson cites Freeman Dyson, a distinguished scholar and not a conventional believer: “The more I examine the universe and study the details of its architecture, the more evidence I find that the universe in some sense knew that we were coming.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It is neither appropriate nor honest to attempt to squeeze astronomers and scientists who are comfortable as agnostics or atheists into the mold of conventional belief. Nevertheless, they do end up asking or confronting profoundly theological questions.

To complicate the public conversation on science, some Christians frequently condemn science and scientific inquiry as the enemy of faith. Is there anything more depressing or ultimately more dangerous than presidential candidates refusing to acknowledge the science of global warming and climate change?

I have vivid memories of my first experience with that kind of closed-minded religion. Home for Christmas after my first semester of studying geology, I told neighbor friends who were fundamentalist Baptists that the world is really old. Creation took millions of years, not six days. My friends were aghast, and they borrowed the family car to take me to an “expert” from their church who confidently explained that the Genesis account of creation was factual. He had simple answers for all my questions and let me know, in no uncertain terms, that what I was being taught in college was not only false but inconsistent with Christian teaching and Christian faith.

That response didn’t satisfy me. In fact, it inspired a lifelong suspicion of religious certainty and of how it easily becomes anti-intellectualism. It also didn’t compute with my sense of my geology professor, who was not only not an enemy of faith but a regular worshiper at college chapel services.

In his interview with Amy Frykholm, Guy Consolmagno, a Vatican astronomer, was asked why the Vatican has an observatory: “Every religion should,” he replied, and expanded: “The tone is set by the person in the pulpit. The keys are curiosity and humility. Religious leaders need to say ‘I don’t know everything, and I wish I knew more.’”

The stars in the sky over Santa Fe, New Mexico, take my breath away the same way they do on summer nights at the ocean. They remind me of a favorite Walt Whitman poem:

When I heard the learn’d astronomer,

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me,

When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them,

When I sitting heard the astronomer where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room,

How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick,

Till rising and gliding out I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.